Finest Hour 196

“These Thankless Deserts”

Winston Churchill and the Middle East: An Introduction

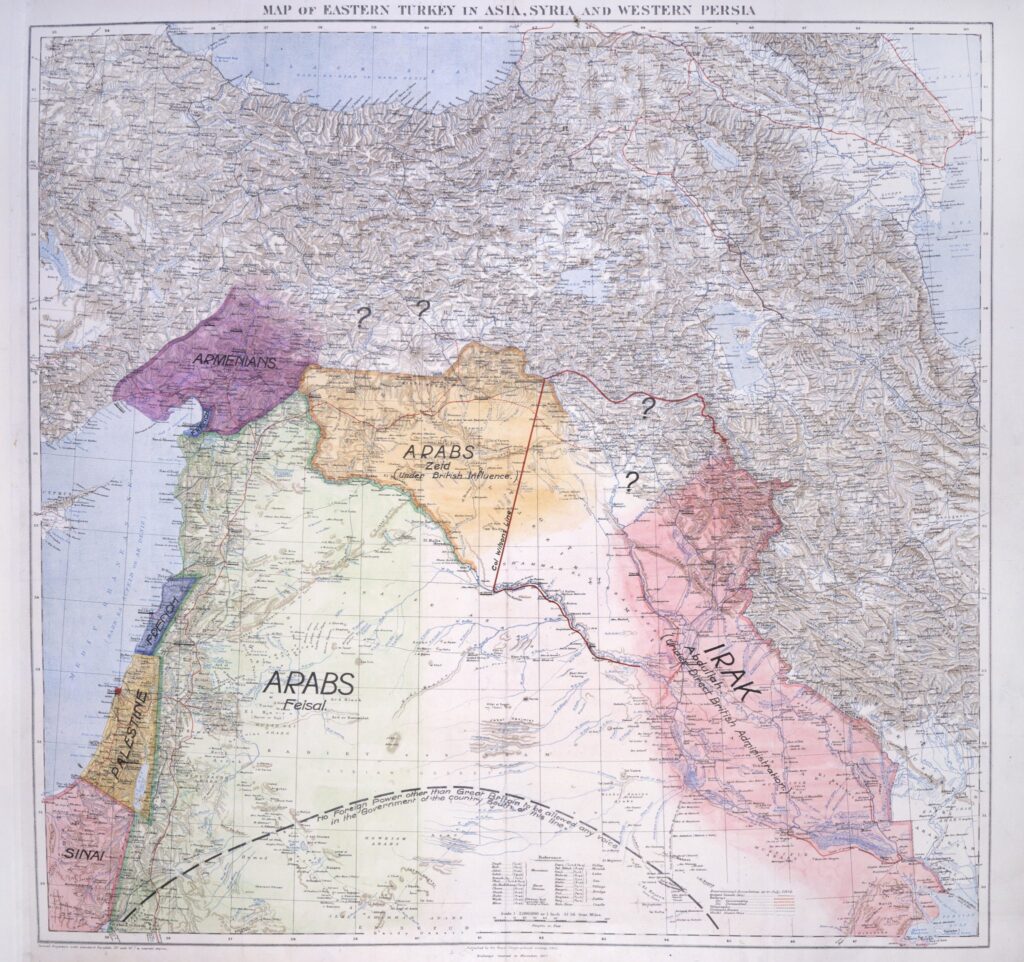

Map presented by T. E. Lawrence to the Eastern Committee of the War Cabinet in November 1918

July 10, 2023

Finest Hour 196, Second Quarter 2022

By DAVID FREEMAN

During the First World War, the United Kingdom went to war against the Ottoman Empire, which had allied itself with the Central Powers of Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Ottoman Empire traced its origins and its name back to the thirteenth-century Turkish Sultan Osman I.

Although once a great power controlling large sections of Europe, Africa, and Asia, the Ottoman Empire by the twentieth century had become known as the “sick man of Europe” and was much reduced in size. Nevertheless, the Turks still controlled nearly all of the lands of Arabia, including the Moslem Holy Cities of Mecca and Medina. For centuries, the office of Sultan had been combined with that of the Caliph, the spiritual leader of the Moslem world.

All of this came to an end with Turkish defeat in the Great War. In 1915, the British attempted a quick thrust at the Ottoman capital of Constantinople (now known as Istanbul) with a plan strongly supported by First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill. The Dardanelles (or Gallipoli) campaign ended in failure. The British then turned to attacking the Turks from further out, along the frontiers of Arabia.

In control of Egypt since 1882, the British used the ancient land to launch an offensive against Gaza, which lay in Turkish-controlled Palestine near the Sinai border with Egypt. At the same time, the British opened talks with Emir Hussein ibn Ali Al-Hashimi, the Sharif of Mecca. The Sharifate included Mecca and Medina, both located in the western regions of Arabia known as the Hejaz. Although an Arab, Hussein served the Turks, his title of Sharif indicating descent from the Prophet Mohammad.

In 1916, the British induced Hussein to declare independence and establish himself as King of the Hejaz. In doing this, the British hoped to bring down the Ottoman Empire from within and minimize the resources they would need to commit to the region. The “Arab Revolt,” however, failed to attract the sort of support for which the British had been hoping.

Much more powerful among the Arabs than Hussein was Abdul Aziz ibn Saud, the dominant chieftain in the Nejd, the large, barren region of eastern Arabia. Ibn Saud was much more concerned with defeating his chief rival in the Nejd than making war against the Turks. And so, in the end, the British had to do most of their own fighting in the Middle East, using forces from Britain, India, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand.

Hussein had several sons. Of these, the one who worked most closely with the British during the war was Feisal, known variously as “Emir Feisal” and, after his father proclaimed himself king, “Prince Feisal.” In return for Arab support, the British made ambiguous promises about supporting the creation after the war of independent states, including the region of Palestine, which was vaguely understood to be the land around the Jordan River.

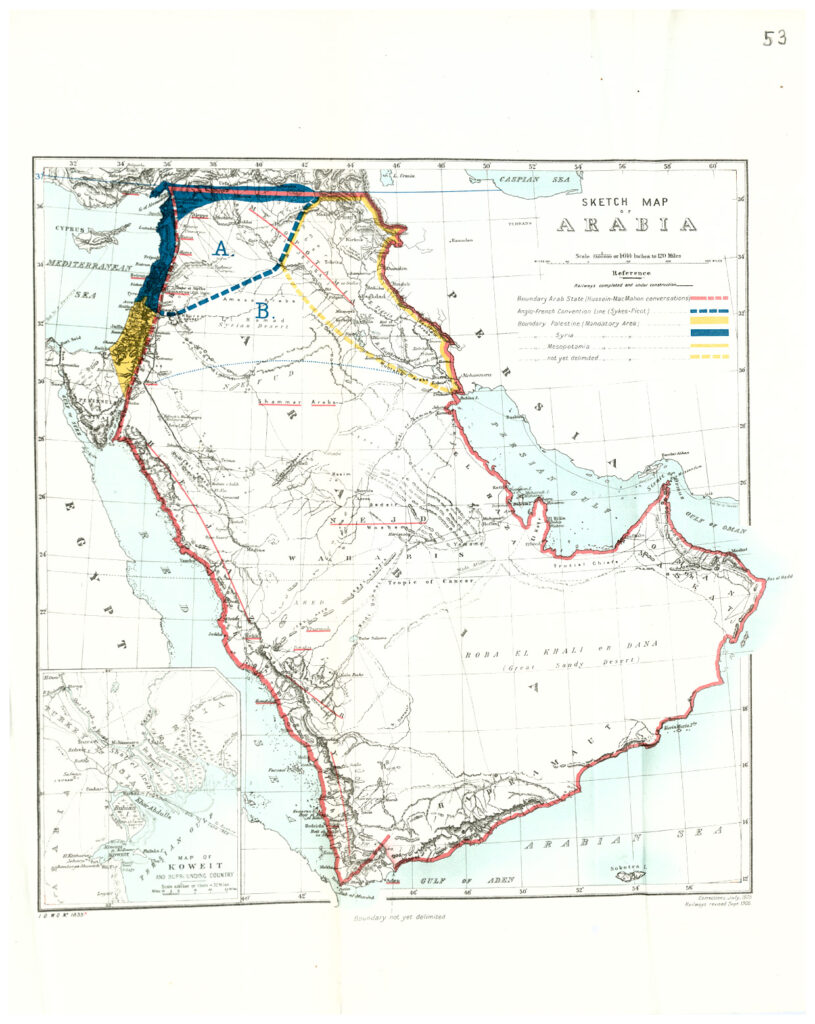

In the search for victory, however, the British also made promises in other directions. In 1916, Britain and France entered into an agreement that became known as the Sykes-Picot Treaty. The two imperial powers decided to carve up the Arab lands once the Turks were defeated. The French would take the northern regions of Syria and Lebanon, which might include Mosul and parts of Palestine, but which would definitely include Damascus. The British would take most of Palestine and Mesopotamia.

In 1917, the British entered into yet another potentially conflicting agreement. Even before 1914, the World Zionist Congress had begun to establish new settlements in Palestine, the ancient homeland of the Jewish people. During the war, Dr. Chaim Weizmann, a naturalized British citizen and a research chemist, provided vital assistance to the war effort as Director of the British Admiralty Laboratories (see FH 195). Weizmann skillfully used his influence to induce the British government to issue the Balfour Declaration, a letter from Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour to Lord Rothschild pledging support for the establishment “in Palestine for a national home for the Jewish people.”

In the final year of the war, British forces made major progress against the Turks. Starting from Basra, at the head of the Persian Gulf, the British swept up the valley of Mesopotamia and captured Baghdad. Under the leadership of Gen. Sir Edmund Allenby, the British Army finally took Gaza and pushed through to Jerusalem. In the interior, meanwhile, Arab forces carried out a guerrilla campaign against the Turks, assisted to a degree by a young archaeologist turned intelligence officer turned commando, T. E. Lawrence (see FH 119).

In the fall of 1918, the Ottoman Empire finally collapsed. Turkish forces remaining in Arabia hastily retreated, creating a vacuum. The Allies had not anticipated this, and Feisal seized the opportunity to establish himself in Damascus with the intention of ruling a new kingdom from the world’s oldest continually inhabited city. The French, however, insisted on their “rights” under the Sykes-Picot agreement, and the British had to acquiesce on the grounds that amity with the French was more important to the United Kingdom than amity with the Arabs.

The French, however, were not to be altogether satisfied. President Wilson of the United States insisted that the Allies were to gain no territory from the defeated Central Powers. Instead the former colonies of Germany and Turkey would come under the authority of the League of Nations, which would assign the various territories to member states with a “mandate” to assist the native populations towards self-government. At least in theory, French and British authority in the Middle East was supposed to be only temporary.

For the most part, the British were anxious to exit their mandates as soon as possible. British forces in Mesopotamia were made unwelcome by the locals, who were also bitterly divided against one another. Chaos prevailed, and British troops were regularly ambushed and killed in what Churchill called “these thankless deserts.” The cost of military operations became a primary concern to Churchill after the Armistice, when he became Secretary of State for War and was told by Prime Minister David Lloyd George that his paramount responsibility had to be reduction of expenditure.

By 1920, Churchill came to believe that reducing military spending in the Middle East required the establishment of an Arab Department within the Colonial Office, which could work to settle the grievances of the Arabs and thereby reduce hostilities in the region. He lamented the price in blood and treasure that Britain was paying to be “midwife to an ungrateful volcano” (see FH 132). After Lloyd George agreed to Churchill’s proposal, the Prime Minister invited his War Secretary to move to the Colonial Office and supervise the settlement process himself.

Churchill became Secretary of State for the Colonies early in 1921 and immediately called for a conference to take place in Cairo that March. Altogether forty key people involved with Britain’s Middle Eastern affairs gathered for what Churchill jestingly called a meeting of the “forty thieves.” Out of this emerged what became known as the “Sharifian” solution.

Hussein would continue to be recognized as King of the Hejaz. His son Feisal, driven from Damascus by the French, would be set up in Baghdad as King of Iraq, as Mesopotamia was formally renamed. Palestine would be divided along the line of the Jordan. The eastern side, or “Trans-Jordania” (later shortened to Jordan), would become an Arab kingdom under Feisal’s elder brother Abdullah. Churchill argued that the advantage of this would be that pressure applied in any one of the three states would also be felt in the other two. Ibn Saud, to keep the peace, would be given a healthy subsidy by the British government.

The western side of Palestine remained under British mandate authority so as to fulfill the pledge made by the Balfour Declaration. Although the Arabs of Palestine (i.e., the Palestinians) protested against this, Churchill curtly rejected their representations during a visit to Jerusalem after the Cairo Conference ended. Churchill did not foresee Jewish immigration overtaking the Palestinian population and naively believed that the two groups, along with Arab Christians, would work together to create a peaceful, prosperous, secular Palestinian state. Churchill was not always right.

In June 1921, Churchill made a lengthy speech to the House of Commons in which he outlined his settlement and the reasons behind it (see p. 38). This would be the longest statement Churchill ever made about the Middle East and its peoples. Over the following year and a half, he supervised the implementation of the decisions made at Cairo and approved by Parliament. The process was not without incident—Feisal was in a precarious position in Baghdad and constrained to demonstrate his independence—but went generally according to plan before Churchill and his Liberal party were driven from power late in 1922.

Churchill’s most dedicated period of involvement with the Middle East ended with his tenure at the Colonial Office, but he continued to monitor events. The short-lived Kingdom of Hejaz ended when it was overrun in 1924 by the forces of ibn Saud, who unified the region with the Nejd to create the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Hussein went into exile, later to be buried in Jerusalem. After returning to Parliament as a Conservative, Churchill remained a supporter of Zionism and strongly objected when the government of Neville Chamberlain acted to restrict Jewish immigration into Palestine, even as Nazi Germany was forcing Jews in Europe to flee for their lives.

During the Second World War, the Middle East became a critical zone for the Allies. The Suez Canal linked Britain with India and the Antipodes, and Egypt was a base from which to fight the Axis powers directly when first Italy and then Germany began offensive operations in North Africa. As Prime Minister, Churchill travelled to Cairo several times during the war. In 1945 it was where he last met with President Roosevelt and first met with ibn Saud. After a cabal of pro-fascist army officers seized control of the government in Baghdad in 1941, Churchill supported a bold and successful move to reestablish an Iraqi government friendly to Britain.

Although out of office when Israel declared independence in 1948, Churchill expressed the view to his old friend and fellow Zionist Leo Amery that it was “a big event…in history” and “all to the good that the result has come about by fighting” (see FH 178). It also pleased Churchill that Weizmann became the first President of Israel and that the nation’s leading technical university chose to name its auditorium for the former British Prime Minister who had supported Zionism at a crucial moment (see FH 195).

One hundred years on, the decisions that Churchill made about the Middle East continue to affect the world today.

David Freeman is editor of Finest Hour.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.