Finest Hour 195

ACTION THIS DAY

Four Scientists Who Made a Difference

Bletchley Park

October 21, 2022

Finest Hour 195, First Quarter 2022

Page 34

David Freeman, January 2022

Quotations in this article are taken from Hinsley et al., British Intelligence in the Second World War, vol. II (London: HMSO, 1981), pp. 655 and 657.

On Saturday, 6 September 1941, Prime Minister Winston Churchill was driven to Ditchley Park, where he would stay on weekends when the moon was full because it was thought to be a less inviting target to the Luftwaffe than the prime minister’s official retreat at Chequers. On the way, the car stopped at Bletchley Park, near Milton Keynes. While Churchill went inside, his Principal Private Secretary, John Martin, remained in the car completely unaware of what went on at the facility, so secret were the activities of the establishment.

Not until more than thirty years later did the world learn that Bletchley had been the wartime headquarters of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS), the facility where scientists, mathematicians, engineers, and cryptanalysts worked to break Axis codes and provide Churchill with intelligence information so vital that it was classified as Ultra Secret. This was Churchill’s first visit to the facility.

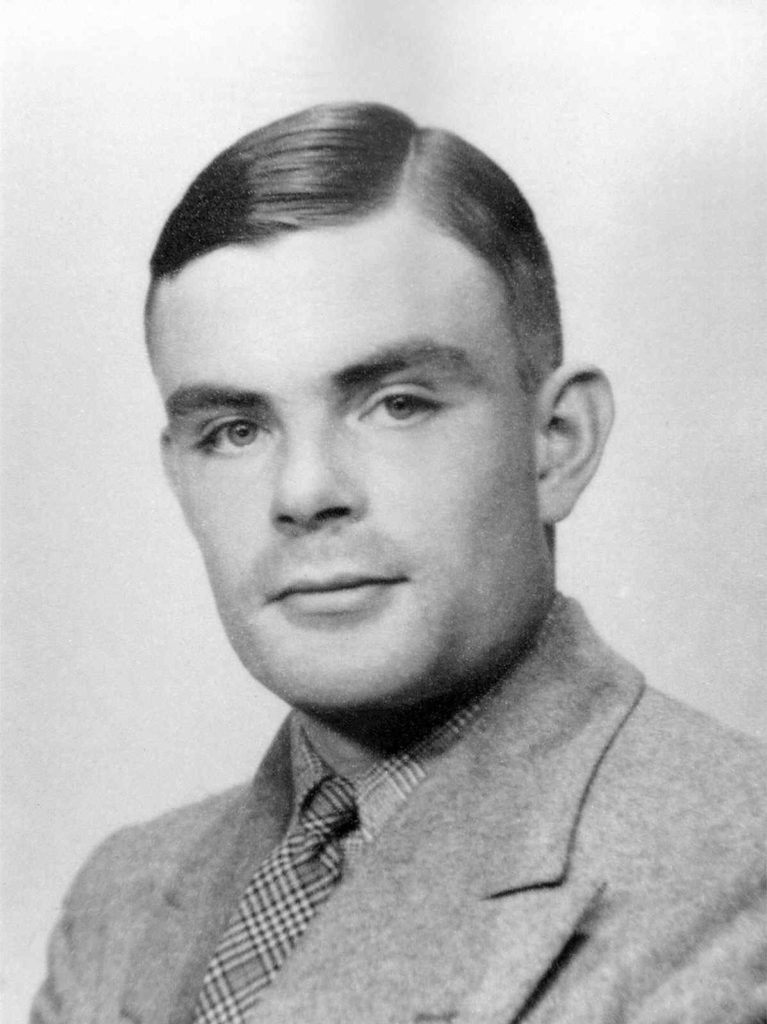

At that point in the war, the key machinery used by the “Boffins,” was the Bombe, a large, electro-mechanical device based on a Polish design, which had been improved upon in 1939 by Alan Turing (1912–1954) with further refinements made in 1940 by Gordon Welchman (1906– 1985). The Bombe enabled the code breakers to narrow down to a manageable number the possible settings used each day by the Germans when moving the rotors on their Enigma machine, a cipher device for scrambling the letters of the alphabet before transmitting messages. Only machines with the same rotor settings could unscramble the messages, and the settings of the rotors (first three, with a fourth added later) were typically changed daily.

2025 International Churchill Conference

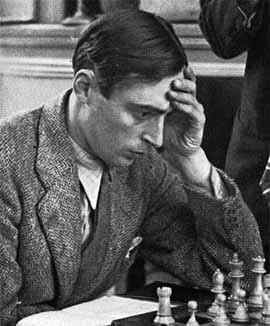

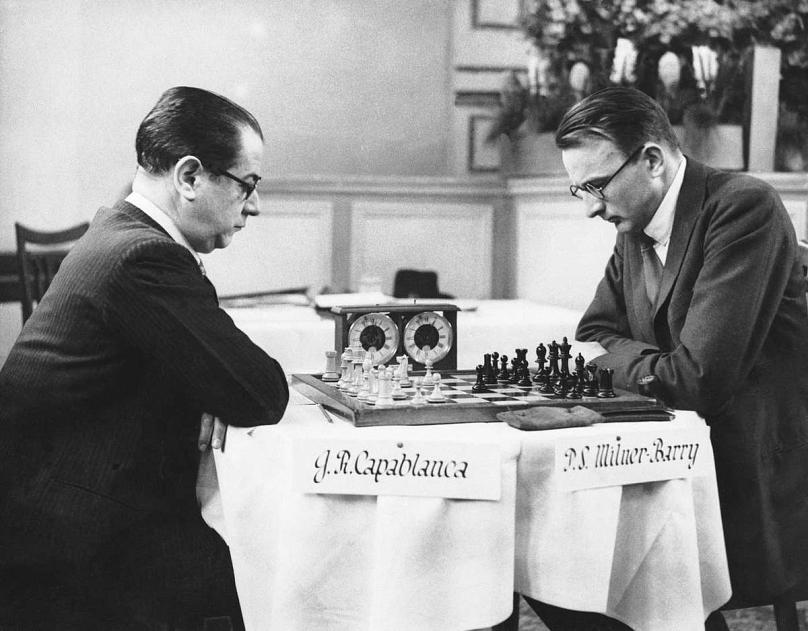

Intelligence gained with the assistance of the Bombe helped the British reduce their shipping losses considerably during the ongoing Battle of the Atlantic. This was crucial. First Sea Lord Sir Dudley Pound put it succinctly: “If we lose the war at sea, we lose the war.” But Turing and Welchman, along with their colleagues Hugh Alexander (1909–1974) and Stuart Milner-Barry (1906–1995), were continually frustrated by the insufficient staff supplied to them and the paucity of resources necessary to build more Bombes in order to support their work. Following Churchill’s visit to Bletchley, the four scientists made bold to write the Prime Minister directly and plead for his assistance.

Because of the exceptional secrecy involved, Milner-Barry hand delivered to 10 Downing Street the letter signed by all four scientists, which began, “Dear Prime Minister, some weeks ago you paid us the honour of a visit and we believe you regard our work as important….” The letter went on to describe the urgent need for additional personnel and resources, while twice stating that they meant no criticism of their superiors at Bletchley.

Churchill responded immediately with a memo headed ACTION THIS DAY that he sent to the head of his Defence Office, General Hastings Ismay: “Make sure they have all they want on extreme priority and report to me that this has been done.” “Almost from that day,” Milner-Barry recalled, “the rough ways began to be made smooth. The flow of bombes was speeded up, the staff bottlenecks relieved, and we were able to devote ourselves uninterruptedly to the business at hand.”

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.