Finest Hour 194

The Statesman as Artist

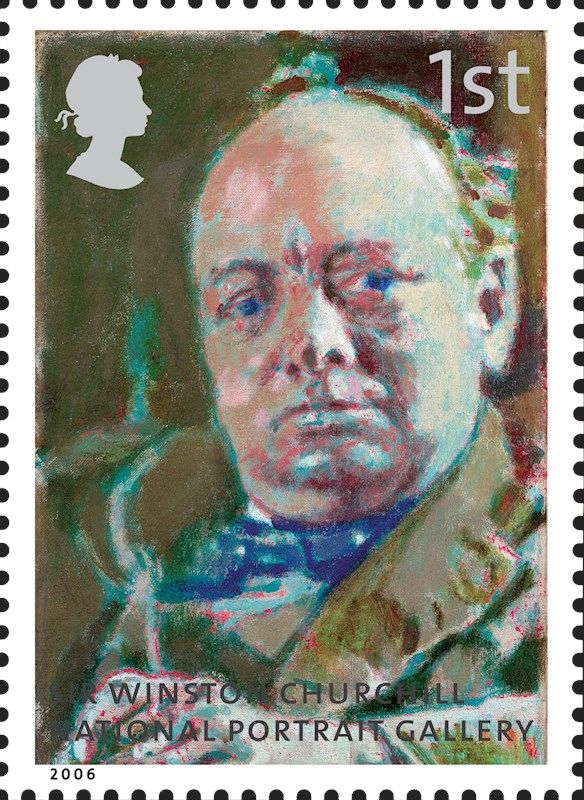

Churchill by Walter Sickert

August 31, 2022

Finest Hour 194, Fourth Quarter 2021

Page 09

By David Cannadine

Sir David Cannadine is Dodge Professor of History at Princeton University. His many books include Churchill: The Statesman as Artist (Bloomsbury, 2018), from which this article is extracted.

During the summer of 1915, Winston Churchill’s spirits were at their lowest ebb in the aftermath of the disastrous troop landings in the Dardanelles at Gallipoli. As the most ardent advocate of what became this doomed operation, Churchill bore the brunt of the blame for the fiasco and was compelled to resign. Out of power, he fell into a depression so severe that his wife Clementine feared he would die of grief.

Shunned by the political establishment, Winston and Clementine sought refuge at Hoe Farm, a small country house they rented in Surrey, where Churchill’s younger brother Jack and his wife Gwendoline (known as “Goonie”) often came to stay. Goonie was an accomplished water-colourist, who brought her brushes and easel with her, and on one such visit she persuaded Churchill to try his hand at painting.

He was immediately captivated and soon changed to oils as being a stronger and more robust medium than watercolours. He sent Clementine to nearby Godalming to buy him paints, and on his return to London he opened an account with Roberson’s, the artist’s supplier in Long Acre, where he made regular purchases of paint, turpentine, canvasses, easels, and other materials.

At the end of 1915, Churchill re-joined the army and briefly commanded a battalion in Belgium on the Western Front. Now a painter as well as a soldier, he took his brushes and canvasses with him, and early in 1916 he completed several sombre pictures of the devastated buildings and war-torn countryside of Flanders. “I think,” he wrote to Clementine, “that painting will be a great pleasure and resource to me—if I come through all right.”

Churchill did, indeed, survive, his political fortunes gradually began to improve, he returned to government in 1917 as Minister of Munitions, and the Great War ended the following year. As his spirits revived, Churchill turned his artistic attention to more cheerful and optimistic subjects, increasingly concentrating on those warm, brightly-lit landscapes which banished depression rather than expressed it, and offered an escape from public affairs.

By this time, Churchill had fallen in love with the Impressionists’ use of light and colour, and their works, along with those of J. M. W. Turner, would henceforward be his inspiration among painters of the past. As he would later put it: “light is life,” and what better antidote to the “black dog” could there be than that?

Great Contemporaries

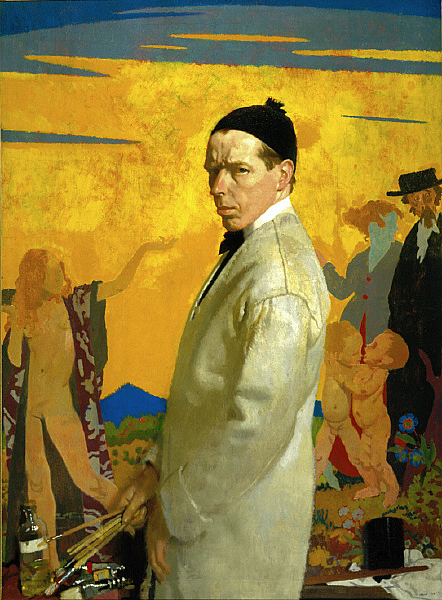

While seeking to improve as an artist, Churchill not only visited galleries to learn from the great painters of the past, but also sought advice from those who were living. The first was Sir John Lavery, who was a neighbour of Churchill’s in the Cromwell Road. In the autumn and winter of 1915, Churchill and Lavery often painted together in Lavery’s studio, and each produced portraits of the other working at their easels.

Lavery’s wife Hazel was also an accomplished artist, and it was she who urged Churchill never to be in awe of an empty canvas; while her husband considered that had Churchill “chosen painting instead of statesmanship, I believe he would have been a great master with the brush, and as President of the Royal Academy would have given stimulus to the art world.”

In 1927, Churchill was introduced to Walter Sickert. For the next two years he offered Churchill advice on how to prepare his canvasses, as well as demonstrating his own techniques for the handling and laying-on of paint. Even more importantly, Sickert taught Churchill how to work from photographs, either as preliminary documents for a painting, or as aides-mémoires to use in his studio when completing a landscape he had begun on-site but left unfinished on returning home. As a result of Sickert’s tutelage, Churchill also went back to painting occasional portraits, but now basing them on photographs. They would, however, never form a major part of his artistic oeuvre.

Churchill seems genuinely to have relished the company of artists, not only as a welcome break from his political friendships (and antagonisms), but for its own sake. He liked art talk and painterly conversation, several artists became lifelong friends, and he would later be deeply saddened by the deaths of Hazel Lavery and Sir William Orpen. During the inter-war years, Orpen, Lavery, Sir Alfred Munnings, and Sir William Nicholson would all be elected to the Other Club—membership of which Churchill regarded as virtually the highest form of recognition that could be bestowed upon anyone. He was also an admirer of the work of Sir Edwin Lutyens, another member of the Other Club, who would serve as President of the Royal Academy from 1938 to 1944.

During the 1930s, the young Kenneth Clark, then Director of the National Gallery, would also become a friend: Churchill invited him down to Chartwell, and dined regularly with him at the Clarks’ grand house at 30 Portland Place. They had further dealings throughout the Second World War, especially while Clark worked at the Ministry of Information, and they remained in close touch thereafter. Clark would be one of the dinner guests at 10 Downing Street, when Churchill suffered a major stroke in July 1953; he would advise Churchill on which pictures to send to the Royal Academy for display in its Summer Exhibitions; and he would recommend Graham Sutherland to paint the ill-fated portrait, commissioned by the Houses of Parliament, to mark Churchill’s eightieth birthday (see story p. 25).

Complete Silence

By the time he was established at Chartwell, the Kent country house he bought in 1922, painting had become an essential part of the settled life Churchill now craved: if the weather was good, he would depict exterior views of the house; if bad, then he would paint still-lifes—fruit, flowers, or bottles—inside; and he soon established his own studio in one of the outbuildings. Across more than four decades, Churchill would eventually complete some 500 canvases—an astonishing output, given the many other calls on his time, energy, and imagination.

By the inter-war years painting had come to rank second to writing among Churchill’s many non-political activities. But there were two significant differences between them. He wrote for serious public purposes: to celebrate his family, to vindicate his political record, to intervene in the political issues of the day, and to make the substantial sums necessary to finance his lavish style of life. By contrast, he painted entirely for therapy and enjoyment: whereas he took pride in being a professional writer, he always regarded himself as merely an amateur artist, and while he wrote for money, he never intended to sell his “little daubs” to increase his income.

Moreover, while Churchill spent most of his waking hours talking incessantly, preparing and making his speeches, delivering monologues at the lunch- and dinner-table, and dictating his journalism and his books, painting was the only activity he seems to have carried out in concentrated peace and complete silence. It absorbed him for many continuous hours, taking his mind off everything else, and off everybody else, too—which was why he found it so therapeutic. Even in his later years of fame and travel, when his expeditions with brushes and paints were accompanied by a large entourage, he would remain focused and hushed before his easel.

The Wilderness Years

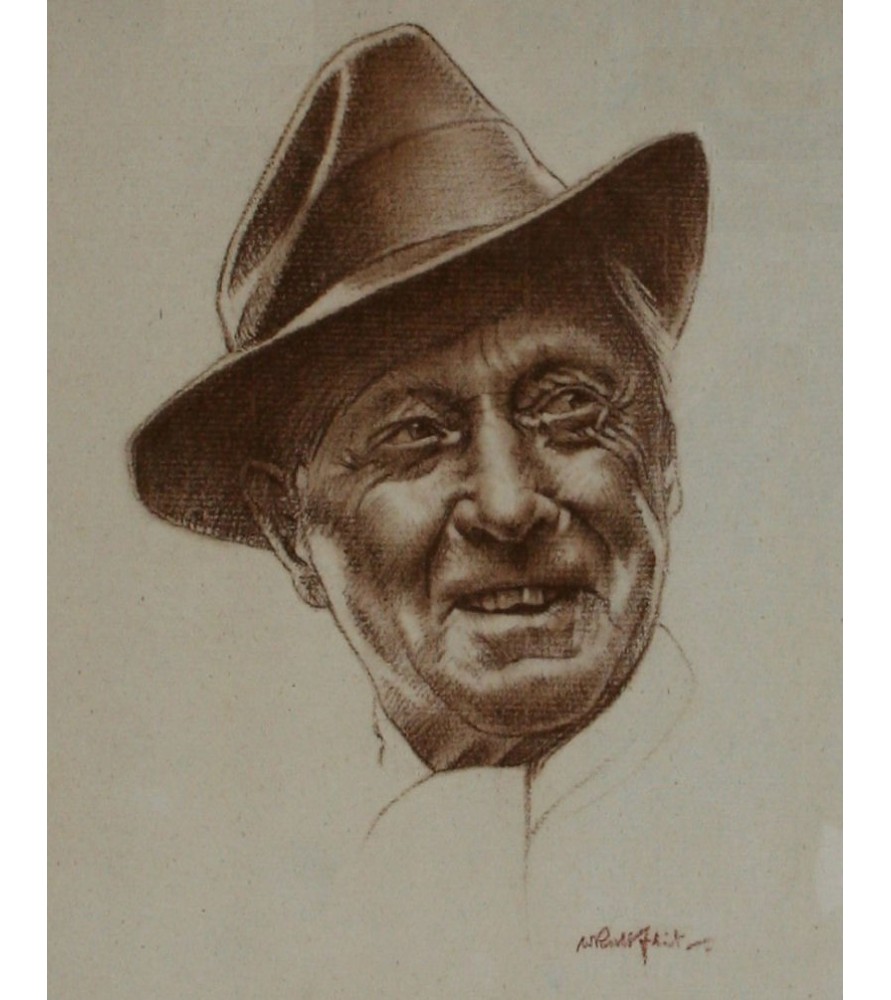

Churchill continued to seek expert artistic advice on into the 1930s, and two more painters became both friendly and influential: Paul Maze and Sir William Nicholson. Maze was a Frenchman who had been a distinguished war artist, with whom Churchill struck up a long and close friendship. But Maze also thought Churchill had been “under the influence of too many people when he began,” and dismissed Sir John Lavery as “slick and superficial.”

Sir William Nicholson was an established portrait painter, and also a landscape and still-life artist, and Churchill would later claim that he was “the person who taught me most about painting.” Clementine was an especially appreciative admirer, because she believed Nicholson’s relatively subdued tones and liking for muted colours softened her husband’s exuberant palette. She preferred Winston’s “sparkling and sunlit scenes” to be “cool and pale à la Nicholson” rather than too highly coloured, as she feared was so often the case.

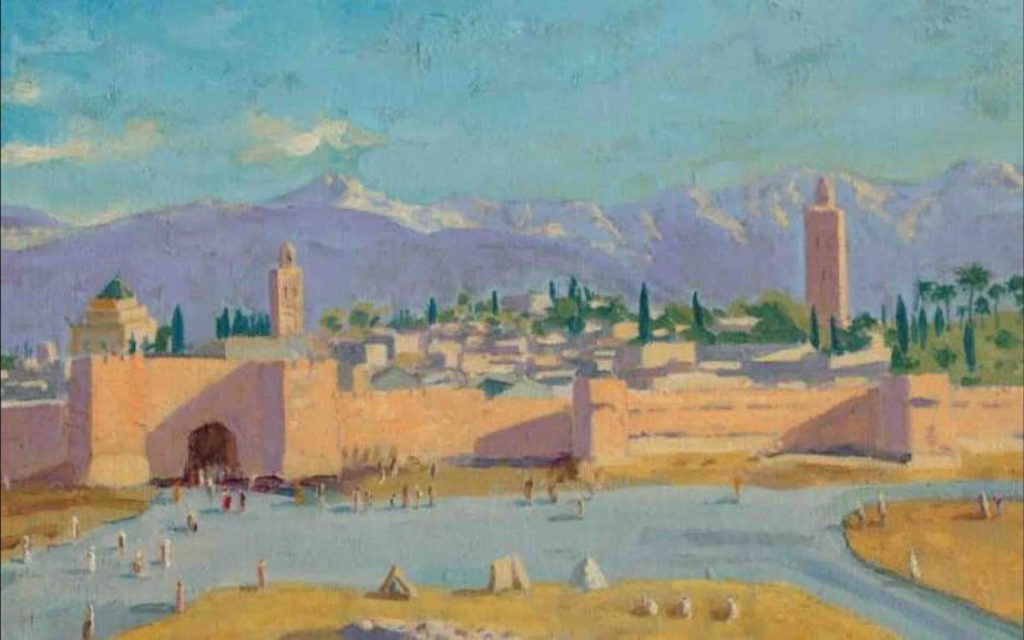

Winston and Clementine disagreed about many things during their marriage, and his paintings were no exception. She thought many of them “over-finished,” and she did not share his liking for the Mediterranean coast, preferring high peaks and snow-covered mountains, by which he was never much enthused. During late 1935, he discovered the painterly delights of Marrakesh, and stayed at the Mamounia Hotel, which was “one of the best” he had ever encountered. Churchill loved the warmth, the sunlight, the gardens, the palm trees, and the views of the Atlas Mountains, and he thought the pictures he painted there “a cut above anything I have done so far.” From the mid-1930s until the late 1950s, Marrakesh would be very special for Churchill, though less so for Clementine.

War and Peace

In the summer of 1939, Churchill completed his final inter-war canvasses in Normandy in the company of Paul Maze. “This is,” he told his friend, “the last picture we shall paint in peace for a very long time.” From the autumn of 1939 until the summer of 1945, Churchill was a titanically busy man, as affairs of state took all of his waking and working hours, and he gave up his brushes and his canvases almost completely.

Appropriately enough, the only canvas Churchill covered while wartime prime minister was of a view of Marrakesh, drenched in sunlight, and rising towards the high peaks of the distant Atlas Mountains, which he painted in January 1943 following his meeting with President Roosevelt at Casablanca. In this century, the painting was purchased by Hollywood power couple Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie. After their separation, “Sunrise at Marrakesh” went under the hammer in 2021 and shattered all previous records for the price of a Churchill painting when it sold for several million pounds.

Just as Churchill had discovered the therapeutic value of painting at the darkest time of his life during the First World War, so he turned to his brushes and canvasses again after his landslide defeat and public rejection at the general election held in the summer of 1945. Even as the votes were being counted, he headed to the south of France in July for a brief holiday, where he set up his easel for the first time since Marrakesh.

And in September, having faced the new Parliament as Leader of the Opposition, he flew to the shores of Lake Como in Italy, where Field Marshal Alexander, the Allied Commander in the Mediterranean, a fellow painter and a Churchill favourite, offered him his villa. As after the Dardanelles disaster, the therapy worked and, within a month, Churchill produced fifteen pictures. “I paint all day and every day,” he wrote to his daughter Mary, “and have banished care and disillusionments to the shades.” “I am confident,” he told Clementine, “that with a few more months of regular practice, I shall be able to paint far better than I have ever painted before. The new interest is very necessary in my life.”

Thereafter, covering canvasses would once more be Churchill’s major relaxation, as he took time off from dictating his war memoirs, from leading the Conservative opposition in Parliament, and from making triumphant visits to the United States and to the capital cities of Europe. “If it weren’t for painting,” he told art historian John Rothenstein at just this time, “I couldn’t live. I couldn’t bear the strain of things.”

By this stage, Churchill’s painting was no longer just a therapeutic exercise and a private hobby: it also became an essential part of his vastly enhanced public reputation, which had taken off in 1940 on both sides of the Atlantic, and which was reinforced rather than diminished, both nationally and globally, by his electoral defeat in 1945. Having led Britain through the Second World War to ultimate victory, and in the aftermath of President Roosevelt’s death in April 1945, Churchill had become the most famous and admired figure in the Western world. Churchill’s artistic endeavours were an essential part of this post-war acclaim and late-life apotheosis, as they became much more widely known and admired.

The Royal Academy

More importantly, it was during these years that Churchill’s relationship with the Royal Academy moved into a much higher gear. This was largely thanks to the initiatives of its President, Sir Alfred Munnings, who had succeeded Sir Edwin Lutyens in 1944. Munnings was a famous painter of conventional sporting scenes, especially fox hunting and horse racing, and he was notorious for his visceral and vituperative hostility to modern, nonrepresentational art. He was also a friend of Churchill’s, and they often saw each other at dinners of the Other Club.

In 1947, Munnings revived the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, which had not been held during the war years, and encouraged Churchill to submit two pictures for consideration, which he did under the pseudonym of David Winter. Both works were accepted, the real identity of the artist was only then revealed, and they were duly put on display, the first time that any British prime minister had exhibited at the Academy. But this was only the beginning, for in 1948, Churchill was elected an Honorary Academician Extraordinary, by the unanimous resolution passed by both the Academy’s Council and its General Assembly. No amateur artist had been recognized before, and none has been so honoured since.

With Churchill’s active prompting and support, Munnings revived the Royal Academy banquet after a lapse of ten years. Churchill was naturally invited, and made a few brief remarks after the dinner, but Munnings delivered an uninhibited and intoxicated speech, broadcast live by the BBC on the wireless, in which he denounced the Academy itself, along with the Arts Council and the Tate Gallery, for their misguided embrace of modern art, inveighed against such “foolish daubers” as Cézanne, Matisse, and Picasso, and insisted that Churchill shared his views. He may have done, but Churchill admired Cézanne and Matisse, and he believed strongly in freedom and artistic expression, and he subsequently rebuked Munnings for revealing and misrepresenting a private conversation. The outrage and embarrassment caused by his remarks was so great that Munnings was compelled to resign the Presidency.

By contrast, Churchill’s relations with the Royal Academy continued to be close and cordial, and he exhibited at every Summer Exhibition between 1948 and 1951. Just as his association with the Academy added to his own lustre and renown, so the Academy’s association with him enhanced its own standing and significance, and Churchill got on well with Munnings’ three Presidential successors, Sir Gerald Kelly, Sir Albert Richardson, and Sir Charles Wheeler.

Later Years

Churchill’s second and final premiership lasted from October 1951 to April 1955, but the continued press of events, combined with advancing years and increasing ill-health, meant that he once again had little time for painting. He covered a few canvasses on his occasional sojourns at La Capponcina, Lord Beaverbrook’s Mediterranean villa, and also on a brief trip to Jamaica. He exhibited every year at the Royal Academy summer show: as Prime Minister and the only Honorary Academician Extraordinary, it was inconceivable that his canvasses would have been turned down, and he was advised by Gerald Kelly and Kenneth Clark as to which pictures to submit. Churchill was also a regular attendee and speaker at the Academy’s annual banquet (see following article).

Immediately following retirement as prime minister, Churchill departed for a holiday in Sicily, where he again rediscovered his pleasure in painting, and did so with “considerable vigour” for three hours at a stretch. During the late 1950s he spent a great deal of time on the French Riviera, but he found spending long hours at the easel increasingly tiring, and he rarely felt “up to it,” either physically or mentally. On his final visit to Marrakesh in 1959, he produced “but two pictures in five weeks.”

If Churchill’s ability to paint slowed, public interest in his painting only intensified. Urged on by his former colleague and fellow soldier-painter President Eisenhower, the Nelson Art Gallery in Kansas City displayed thirty-five of Churchill’s canvasses in January 1958. The show was a record-breaking success, and there followed similar exhibitions across the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Churchill had previously resisted all suggestions that the Royal Academy should mount an exhibition devoted exclusively to his work, insisting that he did not “contemplate such a display in my lifetime.” But the successful displays of his pictures in North America and the Antipodes emboldened the Academy to ask again. This time, Churchill agreed.

The Academy’s display of Churchill’s pictures was much larger than the recent overseas touring shows, and after a private viewing to which Churchill’s extended family and many of his political friends and colleagues were invited, the exhibition opened in March 1959. It was a “phenomenal success,” with 3,210 visitors on opening day—a record for a one-man show. The queues stretched all along Piccadilly, and so great was the demand that its run was extended from the end of May to the end of July, by which time over 140,000 people had visited—a greater number than for any exhibition held in the same spaces of Burlington House except for one devoted to the work of Leonardo da Vinci. There were requests that the exhibition should travel on to Manchester, Cardiff, Belfast, Glasgow, and Edinburgh, but Churchill wanted “the pictures back after their long absence.”

By then, he was visibly ageing, as the “surly advance of decrepitude” was becoming irresistible, and as “the end of the day” drew inexorably closer. Churchill painted his last canvasses at Lord Beaverbrook’s villa in 1960, and there was a final Chartwell picture, of the goldfish pool, two years later (see FH 178); but the optimism, the sunshine, and the vigour that had for so long given his works their warmth and spirit had largely disappeared.

Churchill attended the Academy’s summer banquet until 1963, and he was accompanied by his bodyguard, Sergeant Edmund Murray, who was himself a talented amateur artist. Paintings were submitted on his behalf until the last year of his life, by which time Churchill had contributed more than fifty works to the annual exhibitions. His death in January 1965 severed a connection with the Royal Academy extending back to 1908, when he first spoke at the annual banquet, and with the British art world across more than forty years. As Sir John Rothenstein lamented, “A great presiding presence was no longer there.”

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.