Finest Hour 194

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – Mary Churchill’s Diaries

September 28, 2022

Finest Hour 194, Fourth Quarter 2021

Page 44

Review by W. Mark Hamilton

W. Mark Hamilton is author of The Nation and the Navy: Methods and Organization of British Navalist Propaganda, 1889–1914 (1986).

Emma Soames, ed., Mary Churchill’s War: The Wartime Diaries of Churchill’s Youngest Daughter, Two Roads, 2021, 384 pages, £16.15/$26.95.

ISBN 978–1529341508

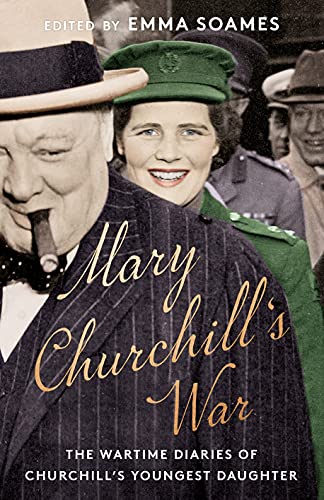

Emma Soames has revealed yet another facet of the life and family of Winston Churchill through the diaries of her mother Mary, Churchill’s youngest daughter, who died in 2014 at age 91. Mary was just seventeen in 1939 when this diary selection begins. The book continues through the end of the Second World War in 1945, and most of the content has never been published. The diary entries are animated by the energy and interests of Mary and the values of her generation.

Mary was devoted to her family and had a special love for “Papa,” who could do no wrong in her eyes. While some of the diary entries are quotidian, Mary—despite her youth—was not only a gifted writer but a sharp observer of the people who surrounded her father. Like him, she did not hold back on her opinions, but the diaries are also full of heart and open a window into history.

2025 International Churchill Conference

Mary describes herself as being “insincere, a coquette, biting her nails, and thinking too much about herself.” Always weight-conscious and worried about being “too fat,” Books, Arts, & Curiosities ISSUE NO. 194 | 45 she admires good looks, especially those of young men, and loves to dance when the opportunity comes along. Her outlook on life is cheerful and optimistic, and the diaries make for happy reading. While some readers may criticize the book for its teenage outlook and some of the inconsequential humanizing revelations about a world leader during a global crisis, those aspects of the book are outweighed by what else it offers: a front-row seat to many of the events and leading personalities of the Second World War from the view of an energetic, youthful, and maturing woman.

Mary shared her father’s love for France, and the French surrender to Germany hit her hard. “Oh, chère France—I can never love you one jot the less—but why have you failed in this.…Now we are alone. May God be with us and grant that we shall not fail.” Mary finds strength and support from her spiritual faith, but she does not wear religion on her sleeve.

As the war rages, its presence is a constant thread in Mary’s diaries. “I have thought more about human suffering and anxiety than ever before,” she writes. “I have seen so many worried and sad and lost expressions.” She traveled sometimes with her father to meet foreign leaders, and the occasional visit from the exiled General Charles de Gaulle to Downing Street leaves her impressed.

In 1941, after a brief courtship, Mary has an ill-fated, eight-week-long engagement to Viscount Eric Duncannon. The engagement dissolves under pressure from her mother and family friends, who oppose the marriage. When these matters of the heart are pushed aside, Mary goes to visit her beloved Chartwell in Kent. (After the war, Mary spent the early part of her marriage to Christopher Soames close to Chartwell, where the couple raised their five children.)

The diaries reflect a self-effacing young woman who is determined not to take advantage of her father’s powerful position. When she was only eighteen, a major turning point in Mary’s young life came with her decision to join the Auxiliary Territories Service (ATS). Though she recounts leaving her family as being painful, she reflects in her diary that her independence is necessary. She now wears a uniform and is assigned to an anti-aircraft battery outside London. Her father was proud of Mary’s decision and visited the gun battery.

Mary’s diaries include accounts of her active social life, as she goes to numerous lunches and dinners, many times surrounded by famous people—about whom she expresses her opinions. She also shares insights into the Churchill family, along with its ups and downs. Her chief family concern is always her father and his health. Mary’s brother Randolph becomes a source of anxiety, with his various sour moods and marital issues. She loves him but seems to lose patience with Randolph’s behavior and loses regard for him as time progresses.

Being a child of Winston Churchill could not have been easy, but Mary concludes early in her diary, “I am not a great or important personage, but this will be the diary of an ordinary person’s life in wartime. Though I may never live to read it again, perhaps it may not prove altogether uninteresting as a record of my life.”

An accomplished editor, Emma Soames is well suited to be her mother’s literary executor. Her professional acumen, combined with her familiarity with the subject matter, make Mary Churchill’s War a significant contribution to the primary literature about Winston Churchill. Major credit must also go to the staff of the Churchill Archives Centre, who served as co-editors.

Emma Soames also proves an excellent writer herself in the essays she has penned to open each chapter of the diaries. These provide context and help to explain events described by her mother. Most useful are the brief biographies Soames has written on the people central to the diaries and the several photos included of people and events discussed in the text.

Though not objective, as no diarist could claim to be, Mary Churchill’s diaries are valuable expressly because of their subjectivity about life in the Churchill family at such a crucial time for Britain and the world.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.