Finest Hour 193

“This Welsh Problem” Churchill and the Creation of a Minister for Welsh Affairs

Gwylim Lloyd George

February 8, 2022

Finest Hour 193, Third Quarter 2021

Page 35

By Adam Evans

Dr. Adam Evans is Clerk of the Welsh Affairs Committee of the House of Commons and Honorary Research Fellow, Cardiff University.

From the late nineteenth century onwards, questions about Wales’s status as a region or a nation and calls for recognition of her distinctiveness became increasingly vocal and significant. This period saw the emergence, and entrenchment, of Welsh political difference vis-à-vis England, initially through the electoral hegemony of the Liberal Party—a dominance that would latter be eclipsed by a Labour hegemony that has seen the party top the poll in Wales at every UK General Election since 1922.

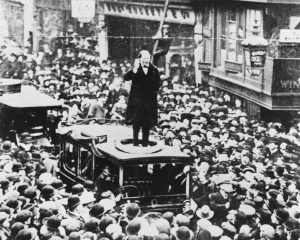

While Welsh political demands were often focussed around issues relating to the Church, education, and land, this period also saw the first flickering of demands for recognition of Wales as a distinct political entity through what we would today consider devolved government. These demands were most powerfully championed by the Cymru Fydd movement, which at one point commanded the support of several Liberal MPs (including the future Prime Minister David Lloyd George) and seemed set to merge fully with organised liberalism in Wales, until, that is, the South Wales Liberal Federation at a famous meeting in Newport in 1896 refused to follow the lead of their North Wales counterparts and merge with Cymru Fydd.

Cymru Fydd’s failure would mark the end of any serious pressure from within Wales for legislative devolution for more than half a century. Recognition of Welsh territorial distinctiveness would instead come in the form of administrative devolution. Administrative devolution had been established in Scotland, in the form of a Secretary for Scotland and the Scottish Office in 1885, but Wales would have to wait until 1964 and 1965 respectively for similar arrangements.1 In the interim, Wales had to settle for a trickle of administrative decentralisation, beginning in 1907 with the creation of a Welsh Department within the Board of Education. In 1911 a Welsh Commission for the administration of health insurance was established, which in turn evolved into a Welsh Board of Health in 1919, and a Council of Agriculture for Wales was also set up that year.

2025 International Churchill Conference

As a result of this patchwork of bodies, the main demand for national recognition, at a political level, came in the form of calls for a Secretary of State for Wales and a Welsh Office. These demands were made on a number of occasions during the interwar period to no avail and were repeated, again unsuccessfully, after the election of the Labour Government in 1945. This latter bid for reform was blocked by the strident opposition of Cabinet heavyweights such as Herbert Morrison, Sir Stafford Cripps, and Aneurin Bevan, and saw the Attlee Government offer what then seemed to be the minor concession of an advisory Council on Wales and Monmouthshire instead.2

The Commitment to a Minister

With administrative devolution on Scottish lines rejected by the Labour Government, it would fall to the Conservatives, then seeking to rebuild after their crushing defeat in 1945, to make the first move in recognising Wales as a distinct nation within the Government’s ministerial ranks. The mastermind of the Conservative offer of a Minister for Welsh Affairs was Enoch Powell, at that point a member of the Party’s Research Department. Tasked with formulating a distinctively Welsh policy for the Party after its defeat in 1945, Powell had, by 1948, reached the conclusion, after some fact-finding visits to Wales, that what was desired was a presence for Wales and Welsh interests within the Cabinet and that such a role could be appended to an existing Cabinet role.3 This suggestion appears to have been rapidly accepted by senior figures in the Conservative party. Indeed, on 26 January 1948, during a debate in the House of Commons on a White Paper on Wales, R. A. Butler, one of the most senior Tories, endorsed the establishment of a “watchdog, a Minister in the Government who can be, so to speak, an Ambassador for Wales.” Such a Minister, Butler suggested, would be neither a “messenger boy” nor have “over-riding” powers and, crucially, would not be such a Secretary of State as existed for Scotland.4

This vision of giving a member of the Cabinet special responsibility for Welsh affairs was reaffirmed by the Conservative Party in its 1949 policy prospectus for Wales and the manifestoes for the 1950 and 1951 General Elections. The 1950 manifesto pledged that “special responsibility for Wales should be assigned to a member of the Cabinet” (for Scotland, the party promised a new Minister of State with Cabinet rank to accompany the Secretary of State for Scotland within Cabinet), and a year later promised that “there will be a Cabinet Minister charged with Welsh Affairs.”

The historian Matthew Cragoe has suggested that these manifesto commitments were part of a broader “discourse of decentralisation” adopted by the Conservative Party as a deliberate strategy to help rebuild its electoral appeal after the 1945 Labour landslide.5 The 1950 manifesto, for example, spoke of the “justifiable grievances” of Scotland and Wales “against the immensely increased control of their affairs from London” and warned that “until the Socialist Government is removed neither Scotland nor Wales will be able to strike away the fetters of centralisation and be free to develop their own way of life.” The 1951 manifesto again adopted this discourse, proclaiming that “the United Kingdom cannot be kept in a Whitehall straitjacket.”

The Appointment of a Minister

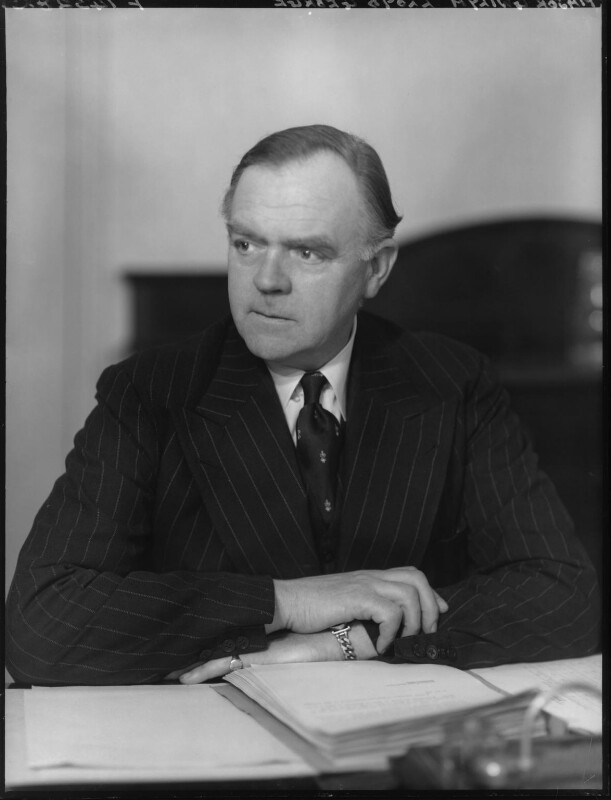

In October 1951, having been returned as Prime Minister after the Conservative Party’s victory at that year’s General Election, Winston Churchill announced that Sir David Maxwell Fyfe would be the first Minister for Welsh Affairs—in addition to his duties as Home Secretary. The decision to add the Minister for Welsh Affairs post to Fyfe’s duties as Home Secretary led to criticisms on two main fronts: first, the part-time nature of the role, and, second and most significantly, the decision to appoint a Scotsman representing an English seat as the Minister for Welsh Affairs.

George Thomas, a Labour MP for Cardiff West (who would go on to become a Cabinet Minister and eventually Speaker of the House of Commons) cut to the heart of the first of those lines of criticism. Thomas raised the spectre of an already busy Home Secretary having to manage his additional responsibilities, suggesting Fyfe would be left saying to himself, “now I can spare a quarter of an hour from my Home Office duties; let us have a look at this Welsh problem.” Thomas went on to query whether the post would be “No. 1 or No. 41 in the duties of the office he [Fyfe] now enjoys?”6

As for the decision to appoint a non-Welsh MP as Minister for Welsh Affairs, this attracted critical comments in and outside Parliament. The Western Mail (the main Wales-wide newspaper), for example, reported on the criticisms that had developed in Wales in the weekend after Sir David’s appointment was made public. One particular display of protest which secured coverage in The Western Mail, as well as in national papers such as The Daily Mail, was the decision by Llanwinio Rural Council (a local council in Carmarthenshire) to pass a motion condemning the appointment.7

Within Parliament, the view of the Labour opposition was summed up by Daniel West, then the MP for Pontypool in South Wales:

Naturally, from the statements made by hon. Members of the Tory Front Bench in the debates in the House on Welsh affairs, the people of Wales were led to expect that when the Conservatives got into power they would, at any rate, have a good Welsh corgi, but when the Conservatives were elected, apparently, the Prime Minister looked round his kennels but he was not able to find a good Welsh corgi. Of course, there is not a good Tory corgi in Wales at all, and so he gave to the people of Wales, instead, a Scottish terrier which had strayed into an English seaport town. I am quite sure that the right hon. and learned Gentleman will not take it amiss when I say that it was a good dog, but of the wrong breed.8

Perhaps sensitive to these criticisms, Churchill appointed a Welsh MP, David Llewellyn (MP for Cardiff North) to the post of Welsh Under-Secretary, a junior ministerial role, to assist Fyfe as Minister for Welsh Affairs.9

Ministerial Responsibilities

On 13 November, in response to a parliamentary question, Churchill outlined the responsibilities of the Minister for Welsh Affairs. As would be clear, the role was envisaged largely along the ambassadorial lines floated by Butler in 1948. According to the Prime Minister:

The function of the Minister in charge of Welsh affairs is to inform himself of the Welsh aspect of business by visiting the Principality and by discussion with representatives of Welsh life and to speak in Cabinet on behalf of the special interests and aspirations of Wales…. It is not proposed to confer executive powers on the Home Secretary as Minister for Welsh affairs and he will therefore have no direct responsibility to Parliament for education, health and agriculture in Wales or for the administration in Wales on any services for which other Ministers are departmentally responsible.

The Minister for Welsh Affairs therefore had limited formal responsibility, beyond an ambassadorial role (what would later be referred to as being Westminster’s voice in Wales and Wales’s voice in Westminster). Even then, this role had to be balanced alongside the onerous day-to-day duties of the Home Office.

It therefore fell upon the “Welsh Under-Secretary” to conduct much of the day-to-day work associated with this new post. As Sir David Maxwell Fyfe explained to the House of Commons on 29 November, the “Welsh Under-Secretary” would be expected to pay frequent visits to Wales (indeed, he was provided with accommodation in Cardiff), and he was to become Chairman of the Conference of the Heads of Government Offices in Wales, which met quarterly. He was also tasked with ensuring that Fyfe was fully briefed and abreast of “major issues of special interest to Wales” which may be discussed in Cabinet, assisting him in relations with the Council for Wales, and would also receive deputations from various Welsh stakeholders.10 If the Minister for Welsh Affairs was to be the Ambassador for Wales in this new cabinet embassy, the “Welsh Under-Secretary” was expected to be a hands-on Deputy Head of Mission.

From a Minister for Welsh Affairs to a Secretary of State

Sir David’s tenure as Minister for Welsh Affairs came to an end in 1954 when he was persuaded to “go upstairs” to the House of Lords as Lord Chancellor. Despite the early criticisms of the choice of Fyfe as the voice of Wales within the cabinet, he earned a degree of affection within Wales. Indeed, within a few months of his appointment, Sir David Maxwell Fyffe had been given the moniker “Dai bananas,” a play on the Welsh diminutive for David (Dai) and the coincidence that he shared a surname with a popular importer of bananas—Fyffes.11

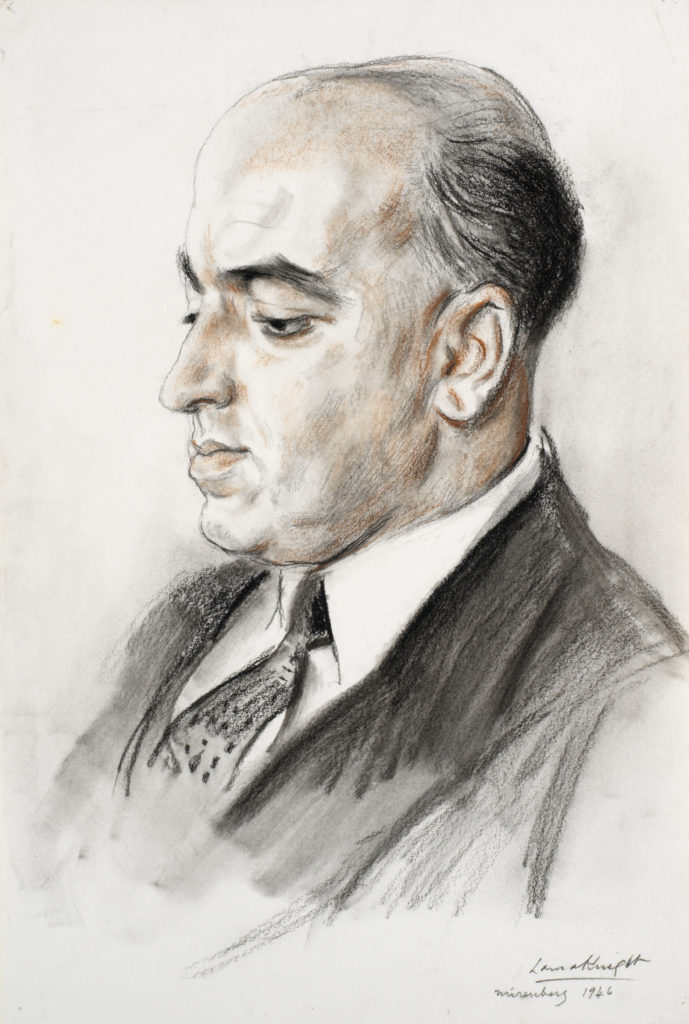

His successor as Minister was a Welshman, albeit one in exile, Gwilym Lloyd George. A member of Wales’s most famous political dynasty and son of the only Welshman (even if he was born in Manchester) to be Prime Minister, Gwilym Lloyd George continued to hold the post as a bolt-on to his day job as Home Secretary. Lloyd George, described as “an able, if not outstanding, minister,” was in post until 1957, when he was reshuffled out by the new Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan.12 At that reshuffle it was decided to move the post of Minister for Welsh Affairs away from the Home Secretary and to add it to the portfolio of the Minister for Housing and Local Government.

From 1957 onwards, the role of Minister for Welsh Affairs was held by successive Englishmen representing English seats: first Henry Brooke, then Charles Hill, and finally Sir Keith Joseph. To compensate those voices, including within the Conservative Party in Wales, who expressed frustration at the continued failure to establish a Welsh Office on Scottish lines, let alone to appoint a Welsh MP as the Minister for Welsh Affairs, Macmillan upgraded the “Welsh Under-Secretary” role to Minister of State status.13

There were, however, growing and increasingly vocal demands for a Welsh Secretary and a Welsh Office. In 1957, the Council of Wales and Monmouthshire, the advisory body established by Clement Attlee’s Government as an attempt to deflect demands for administrative devolution akin to that provided for Scotland, recommended the creation of a Secretary of State for Wales. Two years later, in 1959 the Council returned to the matter, arguing that there was “a clear and unmistakeable need to secure for Wales a different system of administrative arrangements.”14

While these arguments made little headway within the leadership of the Conservative party, the Labour party during its long spell in opposition after 1951 became increasingly supportive of a model of administrative devolution for Wales akin to that in place for Scotland. In its 1959 General Election manifesto, the party concluded that “the time has now come for the special identity of Wales to be recognised by the appointment of a Secretary of State.” The die was cast, and, in 1964, following the election of Harold Wilson’s Labour Party at that year’s General Election, the position of Secretary of State for Wales was created.

Endnotes

1. The Secretary for Scotland would be upgraded to full Secretary of State status in 1926.

2. James Mitchell, Devolution in the UK (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2009), pp. 42–45.

3. Matthew Cragoe (2007), “‘We Like Local Patriotism’: The Conservative Party and the Discourse of Decentralisation, 1947–51,” The English Historical Review, Vol. CXXII, Issue 498, p. 972.

4. House of Commons Debates (HC Deb), 26 January 1948, col. 693.

5. Cragoe, p. 966.

6. HC Deb, 6 November 1951, col. 143.

7. “Protest at Scotsman for Welsh Affairs,” The Western Mail, 31 October 1951, p. 1; “Welsh Protest Against a Scot,” The Daily Mail, 31 October 1951, p. 3.

8. HC Deb, 29 November 1951, col. 1749.

9. Amusingly enough, Llewellyn had been among those to comment publicly on the Prime Minister’s choice of Sir David as Minister for Welsh Affairs. Llewellyn suggested in a Western Mail column that the post might have gone to Gwilym Lloyd George (a Welshman who after losing his Pembrokeshire seat in 1950 had returned to Parliament for an English seat in 1951) had it not been for the prior commitment that the role would go to a Member of the Cabinet (Lloyd George was appointed as Minister of Food, a post which initially fell outside the Cabinet), or to the Liberal Leader and Welsh MP Clement Davies had the latter accepted Churchill’s offer of a coalition government (David Llewellyn, “Scottish Week That Might Have Been Welsh,” The Western Mail, 3 November 1951, p. 2).

10. HC Deb, 29 November 1951, cc. 1743–44.

11. “Dai bananas,” The Times, 24 January 1952, p. 5.

12. Kenneth O. Morgan, “George, Gwilym Lloyd-, first Viscount Tenby,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 6 January 2011 [23 September 2004], https://doi.org/10.1093/ ref:odnb/34571.

13. Lord Crickhowell, “The Conservative Party and Wales,” The National Library of Wales Journal, Vol. 34(1), 2006, pp. 63–65.

14. James Mitchell, “The United Kingdom as a State of Unions: Unity of Government, Equality of Political Rights and Diversity of Institutions,” in Alan Trench, ed., Devolution and Power in the United Kingdom (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007), pp. 45–46.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.