Finest Hour 193

Investing the Prince of Wales – Caernarfon, July 1911

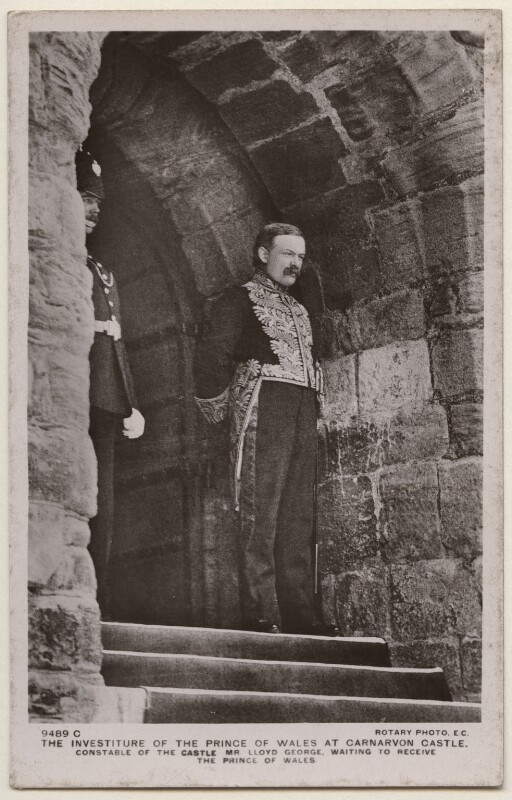

Lloyd George dressed in Privy Councilor uniform waiting in his role as Constable of Caernarfon to present the keys of the castle to the King.

January 9, 2022

Finest Hour 193, Third Quarter 2021

Page 23

By David Freeman

David Freeman is editor of Finest Hour.

In July 1911, Winston Churchill travelled to Wales to take part in the formal investiture of the newest Prince of Wales. The previous holder of the title had acceded to the throne as King George V upon the death of his father Edward VII in May 1910. In accordance with a 600-year-old tradition, George V had then created his eldest son and heir, also named Edward, Prince of Wales. Officially this had been done by letters patent on 23 June 1910, the prince’s sixteenth birthday. The formal ceremony, however, did not take place until more than a year later so that it would come after the coronation of the new king and queen in June 1911.

Not for 300 years had the investiture of a Prince of Wales taken place at Caernarfon Castle on the northwest shores of the principality. The idea of reviving the tradition originated with Queen Victoria’s eldest daughter, who had married the King of Prussia but—while visiting Windsor Castle in 1893—suggested to the Bishop of St. Asaph the notion of once again having a truly Welsh ceremony. Nothing had been done about it when George V himself became Prince of Wales in November 1901, but the bishop recalled the idea when it once again became germane in 1910 and mentioned it to an old political adversary of his, who was by then Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George.

Lloyd George immediately apprehended the value of holding the ceremony in Wales. In addition to being the Member of Parliament for Caernarfon Boroughs, the Chancellor, since 1908, had also been the Constable of Caernarfon Castle. For Lloyd George, the occasion would amount to a royal gift to his constituency with no doubt in the public mind as to who was responsible. It would also reassure traditionalists throughout the United Kingdom, who viewed the Chancellor as a dangerous radical.

2025 International Churchill Conference

King George V also agreed to the idea with alacrity. The country was in the midst of a protracted constitutional crisis that had started when Lloyd George introduced his “People’s Budget” in 1909. Two general elections in 1910 had resulted in a hung parliament and a government formed by the Liberal party dependent on the support of Irish MPs demanding Home Rule as their price, an action that threatened the possibility of civil war in Ireland. In the midst of all this, Edward VII had died, and George V was trying to find his way as a constitutional monarch above the taut political situation. A Caernarfon ceremony would boost the popularity of the Royal Family in Wales and show that the new king felt no animosity towards his Chancellor of the Exchequer.

The Preliminaries

The Royal proclamation announcing the ceremony was issued on 4 February 1911. The investiture of the prince at Caernarfon would take place on 13 July, less than a month after the coronation of the new king and queen at Westminster Abbey in London. Under the direction of architect Frank Baines, seconded from the Office of Public Works, Caernarfon Castle was given a facelift using stone from the original quarries. An imperial flavour was added with the use of oak imported from Canada. The ceremony would take place under a canopy set up in the outer bailey of the castle courtyard. Grandstands were erected to flank the inner and outer baileys with room in between for the participants to process to the ceremonial platform from the castle’s main entrance.

Recognizing that much too large a crowd would be present for the available seating in the courtyard, which was ticketed, Lloyd George arranged for the parade to Caernarfon to pause in Castle Square, where the young prince would speak a few words in Welsh to the gathered throng. For this the prince had been trained at 11 Downing Street by the Chancellor of the Exchequer himself. Wearing regalia of gold specially mined in Merionethshire for the ceremony, white satin breeches, and a purple velvet surcoat, the prince said as loudly as possible to the large audience in Castle Square, “Mor o gan yw Cymru I gyd”—all Wales is a sea of song.1

Lloyd George wisely cast himself in only a small supporting role. He knew that the Royal Family needed to be kept front and center throughout the proceedings. He rode in an automobile to Castle Square and, following the remarks made there by the prince, appeared in full court dress at the castle entrance, where, in his role as constable, he presented the keys of Caernarfon to the king. After that, Lloyd George played no further part in the pageant.

The Ceremony

“The day was intensely hot,” wrote one eyewitness, “Drapery embroidered with the Royal Arms, and with the feathers of the Prince of Wales, covered the ancient grey walls of the castle, while Union Jacks and Welsh Dragons hung from every staff, and waved from every window. Within there had assembled all that was brilliant and representative of Welsh life; while accompanying the Royal Family came a crowd of their most distinguished servants—[including] Mr. Asquith [the Prime Minister, and] Mr. Churchill [the Home Secretary].”2 Thanks to his good friend and political mentor the Chancellor, Churchill had been given a much more prominent role in the ceremony than Lloyd George himself.

Churchill had been at the Home Office since February 1910. In this capacity, he would be the one to read out the letters patent investing the Prince of Wales with his new titles while the prince was presented by others with the paraphernalia of his station. In preparation for the ceremony, Churchill motored to Wales on 12 July. At Penrhos on the Isle of Anglesey, Churchill met the royal yacht Victoria & Albert and was invited onboard to meet with the king. “We have rehearsed the ceremony today with the little prince,” Churchill wrote his wife Clementine, “He is a v[er]y nice boy—quite simple and terribly kept in order.”3

Following the investiture on 13 July, Churchill made a full report to his wife: “It was indeed a beautiful and moving ceremony wh[ich] I witnessed yesterday. The little prince looked & spoke as well as it was possible for anyone to do. The enthusiasm was sincere & unbounded. The great radical crowds gave the King & his son the best of welcomes.” “My reading of the Patent,” Churchill added, “was much praised & I thought went well,” an observation attested to by people other than Churchill himself.4

The proceedings were filmed, and surviving portions of the silent, black-and-white footage can be found online.5 While the canopy over the ceremonial platform had most likely been intended to account for rain, the shade provided a welcome relief to the participants on an unexpectedly hot day as the king placed a coronet on his son’s head and other members of the official party, heavily—and uncomfortably, given the heat—adorned in scarlet and ermine, covered the prince with robes of his own. In the video, Churchill, in the full court dress of a privy councilor, can be seen on the right of the platform. Thirty-five and now noticeably balding, the Home Secretary can be recognized standing bareheaded before putting on his cocked hat.

After the ceremony Churchill returned to the Royal “Yacht & dined again on board.”6 Prime Minister Asquith also joined the dinner, and there, on a pleasant evening off the coast of north Wales, discussions about the continuing constitutional crisis resumed. Resolution would soon come in the form of the momentous Parliament Act of 1911.

Footnote

Churchill had a long and complicated relationship with the Prince of Wales, who later became King Edward VIII and, ultimately, the Duke of Windsor (see FH 184). Characteristic of this is a footnote to the events of 13 July 1911. The coronet that the prince received from his father that day was the same one that had been made for King George V when he had been created Prince of Wales a decade before. After Edward VIII abdicated in 1936, however, he took his prince’s coronet with him into exile. This typically self-centered act of the ex-king was also illegal and meant that a new coronet had to be made for Prince Charles when he was invested at Caernarfon in 1969.

Endnotes

- Philip Ziegler, King Edward VIII (London: Collins, 1990), p. 27.

- John Grigg, Lloyd George: The People’s Champion (London: Eyre Methuen, 1978), p. 304.

- Mary Soames, ed., Winston and Clementine: The Personal Letters of the Churchills (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1999), p. 54.

- Ibid.

- www.bing.com/videos/search?q=1911+prince+of+wales+investiture&&FORM=VDVVXX

- Soames, p. 54.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.