Finest Hour 192

Winston Churchill: The Largest Human Being of Our Time

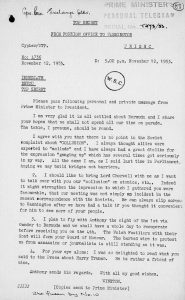

Churchill and Nixon, 1954.

December 15, 2021

Finest Hour 192, Second Quarter 2021

Page 30

By Richard M. Nixon

The International Churchill Society is grateful to the Nixon family for permission to reproduce these remarks. President Nixon’s daugher Julie was a guest at the 2013 Churchill Conference in Washington, D.C., when her husband David Eisenhower, grandson of the President, was the keynote speaker.

Richard M. Nixon (1913–1994) served as the thirty-seventh President of the United States from 1969 to 1974. He frequently said that Winston Churchill was the most impressive man that he ever met. Likely it was as a member of the House of Representatives in January 1952 that Nixon first saw Churchill in person, when the Prime Minister was a guest of President Harry Truman at the annual State of the Union address to Congress. Evidence at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library, however, indicates that, due a family commitment, Rep. Nixon probably missed Churchill’s own speech to Congress that took place a few days later.

Nixon served as Vice President to President Eisenhower from 1953 to 1961. In this capacity, Nixon twice had substantive meetings with Churchill. The first was during the Prime Minister’s visit to Washington in 1954. The second was during the Vice President’s visit to London in 1958. In his 1982 memoir Leaders, Nixon described these meetings in detail, as is shown in the following extracts.

I first met Churchill in June 1954, when I headed the welcoming party that greeted him on his arrival in Washington for his official visit as Prime Minister. I still remember the eager anticipation, even the excitement, that I felt that day as I waited for his plane to come into view. I had already travelled extensively abroad. I had met many national and international leaders and famous celebrities. But none matched Churchill as a larger-than-life legend. In the Pacific during World War II, I had been moved by his speeches even more than by those of President Roosevelt. Since moving into the political arena, I had come to appreciate more than ever what his leadership of Britain had meant to the world during that supreme test of courage and endurance. Superlatives hardly did him justice. He was one of the titanic leaders of the twentieth century.

2024 International Churchill Conference

It was my good fortune that, under the protocol followed at that time, the President went to the airport to greet visiting heads of state, but heads of government first met him at the White House; thus Eisenhower would have greeted the Queen, but it fell to me to greet the Prime Minister.

The night before, I spent over an hour preparing a ninety-second set of welcoming remarks, and I quickly reviewed it in my mind as his plane came into view.

The four-engined Stratocruiser touched down, taxied from the runway, and finally came to a halt in front of us. The door was opened. After a moment Churchill appeared alone at the top of the ramp, wearing a pearl-gray homburg. I was rather surprised that he looked so short. Perhaps it was because his shoulders slumped and his large head seemed to rest on his body as if he had no neck at all. In fact he was five feet eight inches tall [sic: WSC was 5’6”—ed.], and you would never have thought to call him a “little” man, any more than you would have thought to do so with the five-foot-eight-inch Theodore Roosevelt.

His aides were hovering around to assist him down the steps. After quickly surveying the scene and surveying the welcoming party and the cameras down below, he rejected any assistance. Using a gold-headed walking stick, he started slowly down the ramp. He had suffered a stroke the year before, and he was very hesitant and obviously unsure of himself as he took each step. About halfway down, he noticed four Air Force men saluting him and paused momentarily to return the gesture.

We shook hands and he said he was very happy to meet me for the first time. Like so many Englishmen, his handshake was more of a pressureless touch than a firm grasp. After greeting Secretary of State [John Foster] Dulles, he headed straight for the cameras and microphones. Without waiting for me to make my welcoming remarks, he proceeded to make his arrival statement. He said that he was glad to be coming from his fatherland to his mother’s land. (He was referring, of course, to the fact that his mother had been an American.) Amidst the warm applause when he concluded, he flashed his famous V for victory sign and then strode toward the black Lincoln convertible that we would use for the ride to the White House. The remarks I had so painstakingly prepared were never delivered, but neither did they seem to be missed.

A Drive to the White House

As I reread the diary notes that I dictated that day, I am amazed to find that this seventy-nine-year-old man, who had recently suffered a stroke and who had just crossed the Atlantic on an overnight prop-plane ride, could have covered so many subjects so well in the thirty minutes it took us to reach the White House. And all the time he talked, he continually turned to wave to the crowds that lined the route.

He began by telling me that he had followed with interest the trip I had taken to Southeast Asia a few months before. He especially appreciated the fact that during my stop in Malaysia I had gone out into the countryside to visit the British troops who were combating the Communist insurgency there. I told him that I had been very impressed by General Gerald Templer and the other officials who were easing the transition of British colonies to independence. He quickly responded, “I only hope we didn’t give them their independence before they were ready to assume the responsibilities of government.” When I saw him for the last time four years later in London, he again expressed his concern on the same point.

He then commented on Indochina, which I had visited on my Asian trip. He said at the end of World War II the French should have made up their minds whether they were actually going in to save Indochina or whether they were only going to make a halfhearted effort to do so. With his arm still waving to the crowd, he looked over at me and said, “Instead they made the decision to go in, but not to go all out. This was a fatal mistake.”

After a few moments of smiling at the crowd, he looked back at me and said, “The world, Mr. Vice President, is in a very dangerous condition. It is essential for our two peoples to work together. We have our differences. That is normal. That is inevitable. But they are, after all, relatively small. And the press always make them seem larger than they really are.”

This seemingly innocuous exchange in fact had considerable significance. It was clear that he was signaling to me, and through me to the administration, that he wanted to smooth some waters he had troubled two months earlier when Admiral Arthur Radford, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, had visited London. Radford had had a disturbing meeting with Churchill on the subject of Indochina, and the press had subsequently published rumors about it that had strained Anglo-American relations.

Churchill had apparently been annoyed when Radford urged him to help France in its efforts to keep its colonies in Indochina. Churchill churlishly had asked why the British should fight so France could keep Indochina if they would not even fight to keep India for themselves. Radford, not the most diplomatic of men, observed that Congress might not be particularly happy with the British if they refused to go along with our efforts to repel Communist aggression in Asia.

Churchill’s reply to this was blunt: “I’ll be glad when we are no longer dependent on U.S. aid.”

Churchill was reluctant to move against the Communist Vietminh in Indochina because he feared the Communist Chinese might intervene. This, he thought, might lead to war between China and the United States, which would drag in the Soviet Union and make Europe a battleground and Britain a target. But when Radford reported on this meeting to Eisenhower, the President was obviously surprised and shocked that Churchill, the symbol of resistance despite all odds in World War II, seemed almost resigned to defeat in Southeast Asia.

As he continued to wave to the crowds, Churchill expressed his grave concern about the atomic bomb. He said that it was all right for us to talk about retaliating with this “terrible weapon,” but that the theory of “saturation” in connection with nuclear weapons concerned him.

When I told him that I had just finished reading The Hinge of Fate, the fourth volume of his World War II memoirs, he commented that for a period of four months before Roosevelt’s death there was very little communication or understanding between Churchill and the American government. He was surprisingly direct when he added, “President Roosevelt was not himself. And President Truman did not know what he was doing when he suddenly entered upon his great office.” His face became completely serious and once again he ignored the crowds and looked at me. “That was a grave mistake,” he said. “A commander must always keep his second in command informed when he knows that he is ill and that he will not be on the scene for very much longer.”

By now we were nearing the White House. I said after reading his memoirs I often wondered what would have happened if the Allies had accepted his recommendation to launch an offensive against the “soft underbelly” of Southern Europe rather than concentrating on making the D-Day invasion in Normandy. As we turned into the Northwest Gate, he lightly remarked, “Well, it would have been handy to have Vienna.”

Party at the Embassy

The best chance that I had to observe our formidable guest was at the stag dinner at the British embassy on the last night of his visit. Once again protocol kept Eisenhower away, so I was the senior American guest.

Churchill joined us about fifteen minutes late. He greeted all the guests and stood talking for a while, but as Secretary of Defense Charles Wilson embarked upon what was obviously going to be a rather long story, he moved deliberately over to one of the chairs and sat down. I had walked with him, and he looked up at me, grinned, and said, “I feel a little better when I’m sitting down than when I’m standing.”

During dinner I asked him how the heavy schedule of the three-day conference had affected him. He said that except for a few “blackouts” he had felt better during this conference than he had for some time. He added, in his characteristically orotund way, “I always seem to get inspiration and renewed vitality by contact with this novel land of yours which sticks up out of the Atlantic.”

The conversation later turned to a discussion of vacation plans. He said that he was going to travel by sea to Morocco for a holiday. I responded that I always travelled by air because I tended to get seasick. He fixed me with a rather stern but amused gaze and said, “Young man, don’t worry. As you get older, you’ll outgrow it.” I was forty-one years old at the time.

I inquired about his views regarding Soviet leaders who had succeeded Stalin. He said that the West must have a policy of strength and must never deal with the Communists on a basis of weakness. He told me that he was looking forward to visiting Russia, but that he had no intention of making any commitments that would bind the United States.

He mentioned that except for the wartime alliance he had opposed “the Bolsheviks” all his life and remarked that he was “sure that the peoples of the United States would trust me as one who knew the Communists and was a fighter against them.” He concluded by saying, “I think I have done as much against the Communists as [Senator Joseph] McCarthy has done for them.” Before I could say anything, he grinned, leaned toward me, and added, “Of course, that is a private statement. I never believe in interfering in the domestic politics of another country!”

London Visit

I saw Churchill for the last time in 1958 when I went to London for the dedication of the memorial to the American dead in World War II at St. Paul’s Cathedral. I hesitated to ask for an appointment with Churchill because I knew he had not been well. But his aide felt that it would be good for him to talk to someone about problems other than his own physical condition. I had learned long before never to ask a sick man how he feels, because he may tell you. But many, and this is especially true of leaders, want to talk about the world rather than about themselves.

At the arranged time I went to Churchill’s house at Hyde Park Gate. When I was ushered into his room, I was shocked to see how his physical condition had deteriorated. He was in a reclining chair with his eyes half-closed. He looked almost like a zombie. His greeting was barely audible. He weakly held out his hand. He asked his aide for a glass of brandy and, when it arrived, drank it in one swallow. Then he almost miraculously came to life. The light came back into his eyes, his speech was clear, and he became interested in what was going on around him.

I had read in the morning newspapers a report from Africa that Ghana was considering annexing Guinea. I mentioned it to Churchill and asked what he thought about it. “Well, I think Ghana has enough to digest without gobbling up Guinea” he growled. With surprising forcefulness he went on to remark that Roosevelt had forced Britain and the other imperial powers to give their colonies independence too soon. These countries, he said, took on the responsibilities of government before they were ready to do so and were worse off than before. In this he echoed a point he had made as we were driving to the White House at our first meeting four years earlier.

I asked for his analysis of East-West relations. He still held firmly to the view that only if free men are strong can they preserve peace and expand liberty throughout the world. He emphasized that there could be no détente without deterrence.

After about sixty minutes I could see that he was tiring. I knew that I would not see him again so I tried—somewhat ineptly, I fear—to tell him that millions in America and throughout the world would be forever in his debt. I just could not find the right words to express my feelings.

As I rose to leave, he insisted on escorting me to the door. He had to be helped out of his chair and he could only shuffle along the corridor with an aide supporting him at each side.

When the front door was opened, we were blinded by a glare of television lights. The effect on him was electric. He straightened up, pushed the aides aside, and stood alone. I can see him now: his chin thrust forward, his eyes flashing, his hand raised in the famous V for victory sign. The cameras whirred and the bulbs popped. A moment later the door was closed. Right to the end his star shone most brightly when the cameras were trained on him. Old age could conquer his body but never his spirit.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.