Finest Hour 192

Winston Churchill and the Approach to D-Day

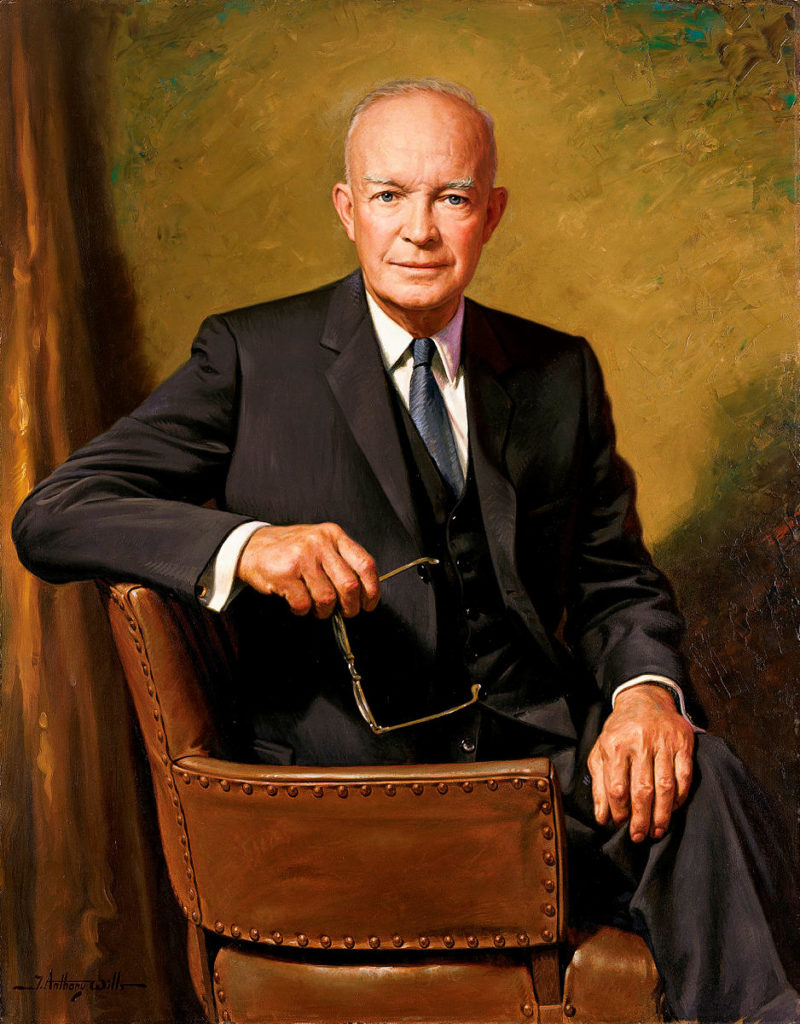

Dwight D. Eisenhower

December 15, 2021

Finest Hour 192, Second Quarter 2021

Page 20

By Dwight D. Eisenhower

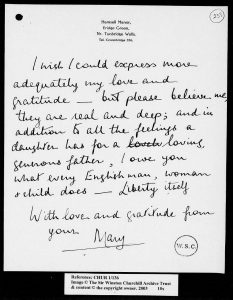

The International Churchill Society is grateful to the Eisenhower family for permission to reprint these remarks.

In 1967 former President Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890–1969) published a collection of memoirs under the title At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends. Unlike his previous books about the Second World War and his service as the thirty-fourth President of the United States (1953–61), At Ease has a casual and affectionate tone. Naturally it includes a pen portrait of working with Winston Churchill during the war. Here follow extracts.

There was a considerable difference in the methods used by the British government and those used by the Americans in communicating with and supporting a theater commander. The American Chiefs of Staff, with the approval of the President, gave the theater commander a mission, provided him with such supplies and troops as they deemed adequate, and let him alone to fail or succeed. If he failed, he was relieved and a new commander assigned. As long as he was succeeding, they largely let him make his own decisions.

The British government, on the other hand, kept in close touch with almost every tactical move in our theater of war. Often suggestions came to us for doing this or that and occasionally these seemed to indicate that London was focusing its attention on side issues.

2024 International Churchill Conference

If the suggestions were political in character, and if the other political leaders approved, they were promptly carried out. When they dealt with tactics, I always answered courteously that I was ready to discuss them with General [Sir Alan] Brooke [the Chief of the Imperial General Staff] or the Prime Minister himself but it had to be remembered that I had the sole responsibility for carrying out the directive of the combined Chiefs of Staff—the defeat of Hitler.

In the reverse situation, the Prime Minister and his government were sensitive, and properly, to anything they thought was a field commander’s intervention into a political situation. One time in the Mediterranean, when we were trying to move air equipment (including steel plates for runways) from Tunisia to the area around Bari, Italy, it became necessary for us to suspend bombing for a few days. Trying to make a virtue out of necessity, we announced that we were giving Italy a short respite, affording the Italian government a chance to quit the Axis and surrender. I had failed to tell the British government in advance why I was doing this. Immediately, I had a copy of a telegram sent by the Prime Minister to President Roosevelt which said there was no excuse for military commanders meddling in things that were essentially political. Of course, when I explained, everything was understood, but the incident did show how carefully the British government followed the detail of military operations.

OVERLORD

We all think back to Sir Winston Churchill as a man who bespoke confidence. There can be no question but that his very presence in the British Isles, a presence of the spirit as much as the mind, is responsible for the fact that those Isles survive today, so that their phenomenally distinguished history reaches into and includes the present. But Winston Churchill was a human being and there were moments when none of us could be sure of success.

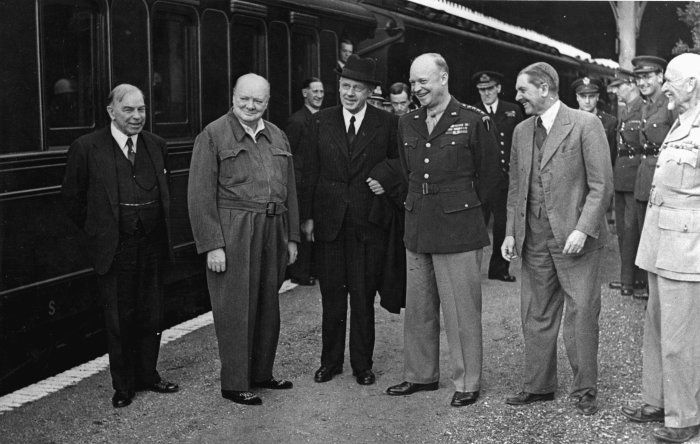

Upon my return to London in January 1944 the Prime Minister and I resumed a habit of meeting at least twice a week. There was luncheon on Tuesday and dinner with the Chiefs of Staff and others on Friday. Occasionally, the dinner would be transformed into a weekend at Chequers, the country residence for the Prime Minister. At Chequers, other guests came for conferences, some rushing in for a few hours, others for the entire time. Fifteen months had wrought a tremendous change in the atmosphere of these meetings.

Early in the fall of 1942, no one could have predicted how or when we would stop the Axis advance, the outcome of our counter-offenses in either theater of war, the survival of Russia as a fighting power, or our own capacity to wage offenses relentlessly on two fronts separated by half the earth’s circumference. But now behind us was success in North Africa and Sicily. In Italy we had advanced almost to Rome, bringing down Mussolini’s government. On the Pacific Front, the Japanese had been driven from Attu and Kiska, outposts of the Western Hemisphere they had occupied in 1942. MacArthur’s troops were leapfrogging up the 1500-mile coast of New Guinea; islands in the southwestern Pacific had been liberated or their Japanese garrisons surrounded. Above all, clear to everyone, friend and foe alike, was the increasing might of the United States in men and weapons.

Nevertheless, in the meetings, tension and anxiety were inescapable. Across the Channel, scant minutes by air from our headquarters, was Festung Europa. Behind the dunes and low cliffs the Nazis had through four years been fortifying beaches and ports. These were supported by mobile reserves who could be rushed to any point we might choose to assault, concentrating masses of armor and infantry against the relatively small numbers we could land by sea or from the air. Our lines of support, on the other hand, would be subject to fatal interruptions by stormy weather, by undersea attack, and, it was rumored, by assault from new projectiles whose range and speed would change the nature of the war.

For the sort of attack before us we had no precedent in military history. Caesar and William the Conqueror had crossed the Channel to invade England successfully. But the England of that day was not guarded by an almost unbroken perimeter of guns and fighting men. Armies from Britain had been put ashore on the European coast—but they had always landed where friendly countries possessed a stretch of the frontier or where the defenders were weak. OVERLORD was at once a singular military expedition and a fearsome risk.

Initial Doubts

It became quickly obvious that the Prime Minister was not oversold on its value, at least in the early spring of 1944. He felt that it would be far better for the Western Allies to wait for more significant signs of German collapse. Sometimes, in his contemplation of the possibilities before us, he spoke as if he were addressing a multitude. He would say, “When I think of the beaches of Normandy choked with the flower of American and British youth, and when, in my mind’s eye, I see the tides running red with their blood, I have my doubts…I have my doubts.”

There were doubts in many quarters. Some inevitably found their way into newspapers. During the spring, an expert opinion was offered by one writer who said that any attack on the northwestern coast of France would certainly create casualties on the order of 90 percent. Because this prediction was highly publicized, [Gen. Omar] Bradley and I decided that we must stress in all our meetings with American troops that such stories were nonsense. We were convinced that we were not going to have unusually heavy losses and we expressed our confidence that the Allies could successfully carry out the mission prescribed by the combined Chiefs of Staff and by our two governments. In this role, Bradley was superb.

While Winston might at times express his doubts in the close confines of an intimate meeting, he would never show pessimism or hesitancy in public, nor would he allow any expression of his to be distorted into the kind of article that had so disturbed

Brad and me. Among ourselves, the Prime Minister would add, following his expression of doubt, “We are committed to this operation of war. And we must all, as loyal Allies, do our very best to make it a success.” This I knew to be the true Churchill speaking and I always believed that his uncertainty about the wisdom of undertaking OVERLORD in the spring of 1944 was the result of the tragic experiences in World War I, when, in spite of tremendous British losses at Paschendaele, Vimy Ridge, and Ypres, their gains were often measured only in yards.

Growing Confidence

As for the American commanders, our confidence grew by leaps and bounds. We saw that our bombing operations were damaging German communications. We constantly cut into their supplies of fuel. We were destroying equipment and production capacity while, in the meantime, the Russians were making inroads on the Eastern Front. There was little opportunity for Hitler to reinforce the west even though he was aware that sooner or later we were going to attack. This confidence and optimism radiated. In private meetings, Winston said, more than once, “General, it is good for commanders to be optimistic, else they would never win a battle. I must say to you if by the time snow flies you have established your thirty-odd divisions, now in Britain, safely on the Normandy coast and have the port of Cherbourg firmly in your grasp, I will be the first to proclaim that this was a gigantic and wonderfully conducted military campaign.”

Then he added: “If in addition you should have seized the port of Le Havre and have extended your holdings to include all the area including the Cotentin Peninsula and the mouth of the Seine, I will proclaim that this is one of the finest operations in modern war.”

And finally, “If by Christmas you have succeeded in liberating our beloved Paris, if she can by that time regain her life of freedom and take her accustomed place as a center of Western European culture and beauty, then I will proclaim that this operation is the most grandly conceived and best conducted known to the history of warfare.” To this, I invariably replied, “Mr. Prime Minister, we expect to be on the border of Germany by Christmas, pounding away at her defenses. When that occurs, if Hitler has the slightest judgment of wisdom left, he will surrender unconditionally to avoid complete destruction of Germany.”

Once I smiled. “Because of this conviction, I made a bet with General Montgomery some months ago. The proposition was that we would end the war in Europe by the end of 1944. The bet was for five pounds and I have no reason to want to hedge the bet.”

The Prime Minister’s face curved upward into a splendid smile, “My dear General, I pray you are right.” Ultimately, we held two substantial command and staff conferences to review planning and expectations for OVERLORD. At one of these there was assembled under a single roof as much civilian and military rank as may have ever been gathered for an operational briefing. Present were the King of England, his Prime Minister, several of the War Cabinet, all the British Chiefs of Staff, and all senior commanders of the proposed operation.

The meeting was notable for me not because of the group itself but because of a statement by the Prime Minister. When the presentations were over, he said, “I am hardening towards this enterprise.”

Winston repeated this two or three times and its meaning—certainly as far as the American present were concerned—was that while he had been long doubtful of the wisdom of OVERLORD, after hearing the explanations of the kind of resistance that we expected to encounter, the help we would get from the air and naval forces, and the special equipment we had for landing purposes, he had changed his mind and got caught up in the atmosphere of confidence and conviction. The smell of victory was in the air.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.