Finest Hour 192

Truman Visits Chartwell

The Trumans' Chartwell visit, 24 June 1956.

December 15, 2021

Finest Hour 192, Second Quarter 2021

Page 15

By Katherine Carter

Katherine Carter works for the National Trust as Property Curator at Chartwell.

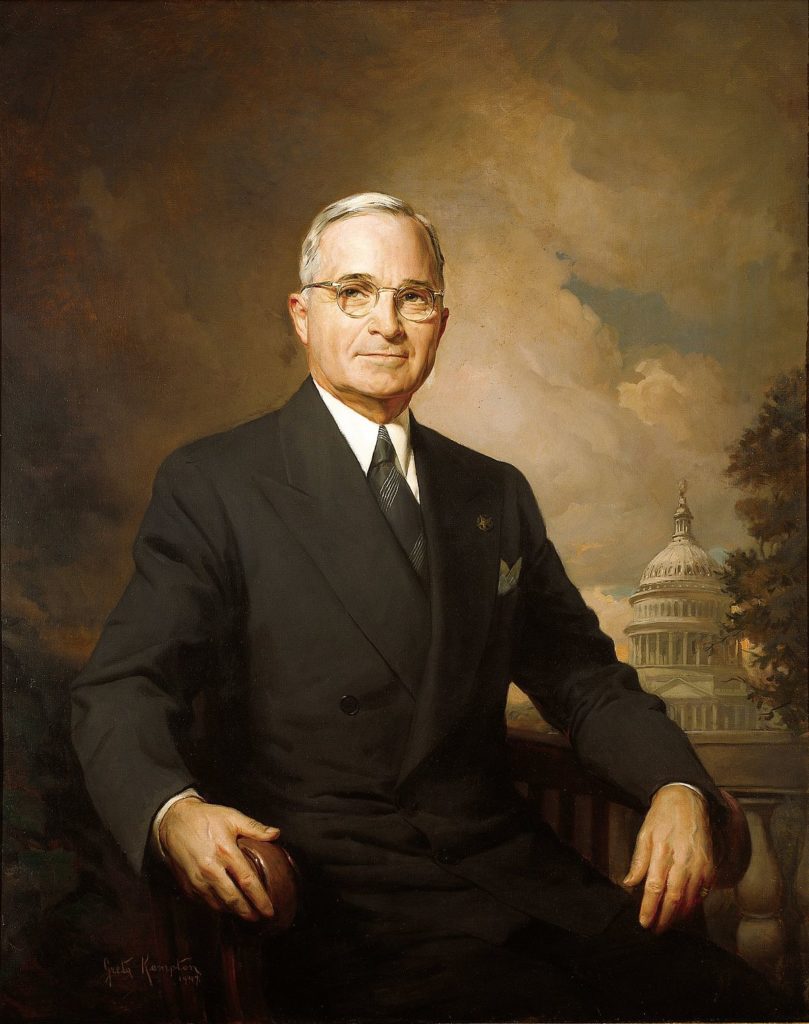

Harry S. Truman (1884–1972) was the thirty-third President of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. He and Churchill met several times over the course of eleven years. Truman also has the distinction of being the only American president to have visited Churchill at Chartwell. Chartwell Curator Katherine Carter looks at the Churchill-Truman relationship by examining some of the artefacts in the house’s collection.

When former President Harry S. Truman visited Winston Churchill at his home at Chartwell, he became the most powerful politician ever to walk through the magnificent oak doors of the Churchills’ country home. Despite the family having welcomed the great and the good of the mid-twentieth century, from royalty to film stars and from artists to military leaders, Chartwell gatherings were usually small-scale, intimate affairs. You had to be someone either very close to the Churchills or very much admired by them in order to receive an invitation to Chartwell. For this reason Truman’s visit offers a unique prism through which we can view the relationship between two major figures in history.

Writing this as I am from my desk at Chartwell, I often find myself making connections between those whom the Churchills entertained here and the collection for which it is our privilege to care and share its stories with the quarter-of-a-million visitors who come here every year. The “special relationship”—and Churchill’s own relationship with America and Americans—is a constant thread throughout the rooms of this house, and the dynamic between him and President Truman is no exception. When considering key moments in the pair’s association, with the Chartwell visit effectively the finale, it is striking how many key moments can be seen through the collections housed at Chartwell today.

2025 International Churchill Conference

First Contact

On 12 April 1945, following the sudden death of President Franklin Roosevelt, Truman became the thirty-third President of the United States only eighty-two days after becoming Vice President. He succeeded a man who had dominated America’s political landscape for the past twelve years. Roosevelt’s death not only shocked the nation: it also risked destabilising the relationship between the United Kingdom and the United States, which Churchill had carefully cultivated.

The impact of FDR’s death on Churchill can be seen in an unassuming display case at Chartwell in which Churchill himself kept his most cherished medallions—from the fencing medal from his schooldays at Harrow to the rare gold medallion depicting the first Duke of Marlborough on horseback at the Battle of Blenheim. Alongside these, Churchill placed the Franklin D. Roosevelt Memorial Medal, a gold medallion struck in the president’s memory with the words “For Country and Humanity” above a seated mourning figure. Roosevelt is the only one of Churchill’s political contemporaries represented in this case, which is shown today exactly as it was during Churchill’s lifetime.

In the aftermath of Roosevelt’s death, Churchill knew he had to move quickly to build a relationship with Truman. With the war still raging, the need for urgent communications between president and prime minister continued. Early telephone calls between the two men included those discussing the terms of Germany’s surrender. The transcription of one such call on 25 April 1945, less than two weeks after Truman was sworn in, tellingly reveals Churchill employing his trans-Atlantic charm offensive once again, quickly creating a sense of rapport and like-mindedness between the two men:

Truman: I hope to see you some day soon.

Churchill: I am planning to. I’ll be sending you some telegrams about that quite soon. I entirely agree with all that you’ve done on the Polish situation. We are walking hand in hand together.

Truman: Well, I want to continue just that.

Churchill: In fact, I am following your lead, backing up whatever you do on the matter.1

Churchill and Truman quickly developed a strong relationship, with Churchill acting as a firm supporter of the new President, calling him “the type of leader the world needs when it needs him most.” Their alliance, however, would not translate to an in-person connection until several months later, when “The Big Three” would meet to determine the future of a post-war world.

Potsdam

The Potsdam Conference in July 1945 provided the medium for the pair’s first face-to-face meeting. With Stalin and Churchill having met on several occasions over the course of the Second World War, Potsdam was the occasion that first saw President Truman represent the United States on the world stage. Churchill, meanwhile, Britain’s victorious wartime leader, appeared at the zenith of his popularity and had spent recent weeks campaigning in the General Election in Britain. It was widely believed that Churchill, the war hero, would be unbeatable, resulting in a resounding Conservative victory. Polling took place on 5 July, but in order to allow time for the ballot boxes to be collected from servicemen overseas, the count would not begin until the 25th.

The conference took place somewhere between war and peace, with guns having fallen silent in Europe but with fighting continuing in East Asia. Truman and Churchill had differing objectives at the outset of the conference. Truman’s goal was, as it had been for Roosevelt at Yalta, to urge the Soviets to enter the war against Japan. British leaders, however, focused on the future of Eastern Europe and Germany.

It was mid-way through proceedings at Potsdam that votes in the 1945 election were finally counted. Churchill’s Conservative Party suffered a crushing defeat. Labour’s victory meant Churchill would lose his seat at the table and be replaced by Clement Attlee, who went to Potsdam as Prime Minister on 28 July. By that time, a number of issues had been settled bilaterally between the American and Soviet delegations, resulting in the remark that the Big Three had become the “Big 2½.”2

Following Churchill’s departure from proceedings at Potsdam, a message was sent to him from Truman, Stalin, and Attlee in order to thank him for the role he played, particularly noting “the untiring efforts and the unconquerable spirit with which at earlier conferences and throughout the war he served our common cause of victory and enduring peace.” Though written almost as a farewell, this was not the last time that President Truman and Winston Churchill would meet. Churchill soon took on the new role of Leader of the Opposition, retaining his place on the world stage.

North America

It was just a few months after Churchill’s departure from Potsdam that he received an invitation to speak as part of a lecture series being held at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri. The invitation included a note from President Truman himself saying, “This is a wonderful school in my home state. Hope you can do it. I’ll introduce you.” The addition of this handwritten note from the President undoubtedly influenced Churchill’s decision to accept at a time when he was receiving invitations to appear from all over the world. Most had to be declined with thoughtfully worded apologies penned by his secretaries.

Churchill’s visit to the United States in 1946 was a lengthy one, and he balanced his time between work and pleasure. He had already been planning a trans-Atlantic journey, with time scheduled in Miami for the several weeks at the start of the year. The invitation to speak at Westminster College in March provided a particularly welcome addition to his itinerary. It gave him a perfect opportunity to voice his concerns about the growing threat of the Soviet Union to world peace. In addition, the presence of the President guaranteed a worldwide audience at a time when Churchill was keen to remain in the public eye and position himself as an authority on international relations in the post-war world.

The early portion of Churchill’s trip took place as planned, with Miami providing a particularly welcome backdrop for his artist’s eye. He completed a number of paintings during his stay in Florida. Churchill’s seascapes and depictions of water are among my favourite of his artistic works and, of those on display at Chartwell, the painting “The Surf Club at Miami, 1946” is no exception. With the sense of energy from the crashing waves and stormy skies looming overhead, the composition appears symbolic of the growing Soviet threat and the peril facing the western world. After all, it was during his time here that he undertook much of the preparation for the speech he called “The Sinews of Peace.”

Following his time in Miami, and a brief visit to Cuba [see FH 171], Churchill travelled to Washington, D.C., and it was from there that he and the President started their journey by train to Jefferson City, Missouri. Travelling more than a thousand miles gave the pair considerable time together. By the end of the journey, which had been only their second meeting, the two men were on first name terms and had spent most of their time playing poker, with Truman and his aides winning most of the games.

The lecture at Westminster College drew crowds of thousands, overwhelming for an academic institution with just a few hundred students. The speech that Churchill gave, which will be known to most readers as “The Iron Curtain Speech,” is universally regarded as his most significant while Leader of the Opposition and among the most important he ever made. His words, spoken with Truman seated beside him, sounded the alarm on the fracturing relationship between the superpowers. For Truman, who had read a copy of the speech on the journey from Washington, its content “would do nothing but good, though it would make a stir.” In turn, it is likely that his administration welcomed the speech and its resulting global coverage as a harbinger of its own emerging campaign to shift public opinion towards confronting the USSR. In due course, the speech’s importance paved the way for ongoing closeness even beyond Churchill’s lifetime between the office of the President of the United States and the Churchill family. This can be seen in the gift of a gold medal from Westminster College presented to Lady Churchill by President Richard M. Nixon in 1969, which remains on permanent display in the Museum Room at Chartwell.

After Churchill became Prime Minister again in October 1951, he quickly arranged an official visit to meet with President Truman in Washington in January 1952. Before boarding the flight from London, Churchill told a press conference, “Our two governments must understand each other’s points of view and do all we can to work together for the common cause, trusting we will be able to build up that common understanding and intimacy which enabled us to go through safely in the past and without which no full settlement of new problems can be reached.” Once in Washington, the pair made a joint appearance at which Truman commented, “Great Britain and the Commonwealth and the United States are the closest of friends and you and I want to keep it that way.” The mirroring of both tone and sentiment was already showing a synchronicity between the two leaders.

These remarks were followed by lunch and then a cruise on the presidential yacht Williamsburg, which lasted for approximately two hours. Despite reports beforehand that the two leaders’ relationship might be strained by differences of opinion over policy in the Middle East and Asia, a spokesman later said that the talks had “clarified the atmosphere.” A photograph in Chartwell’s collection captures this moment. It includes a handwritten note from President Truman reading “To my good friend Winston in rememberance of a very happy visit. The Williamsburg. June 5, 1952. Harry Truman.”

Chartwell

As it turned out, the official visit of 1952 was among the pair’s last meetings. Their very last took place after both had men retired, though Churchill still represented his constituency of Woodford as their Member of Parliament. Truman had travelled to Britain in the summer of 1956, his only peacetime visit to the country. During their stay, President Truman and his wife Bess went to Kent to visit the Churchills at Chartwell. Recalling their visit, Truman later described the moment, saying, “Sir Winston and Mrs. Churchill met us at the door. We stopped for pictures. Many of the neighbor people were at the gate. They gave a wave and a cheer as Mrs. Truman and I entered.”

As they walked around the gardens, Churchill and Truman discussed the past, including their first meeting at Potsdam. They stopped to feed the fish in the ponds and watch Churchill’s grandchildren playing together. Churchill also reportedly said that he thought Truman should run for the presidency once again, though Truman quickly rebutted that idea.

The visit, however, was relatively fleeting. It took place just before luncheon, which was different from the more typical “dine and sleep” stay for Chartwell guests. Truman later remarked that the occasion was over too soon. Fortunately there was enough time for the Churchills’ Visitors Book to be displayed and made available for the distinguished guests. Perhaps rather tellingly, Truman’s entry is one of only a handful of the 2000+ signatures that includes a comment alongside, with the President proclaiming, “What a grand climax to a great visit!” To this day the Churchills’ Visitors Book remains one of the most important objects in the entire collection at Chartwell, providing a completely unique and incomparable record of the private lives of Winston and Clementine.

The sense of camaraderie continued in the note Truman penned to Churchill a fortnight later in which he said that the meeting had been a highlight of their stay in England: “I do not know when I have enjoyed a visit more than ours at Chartwell.” This was high praise indeed, given that two days after seeing the Churchills the Trumans had dined at Buckingham Palace with the Queen and Prince Philip.

When the pair said goodbye on the doorstep of Chartwell, they could not have known that it would be the last time they would meet. Despite this, they remained friends for the rest of their lives. This can be seen in the penultimate letter ever written from Truman to Churchill, which concluded: “As time goes on my admiration for your great contribution to the winning of the war and the establishment to organisation for the peace continues to grow.”3

Endnotes

1. Transcript of Trans-Atlantic Telephone Conversation Between President Truman and British Prime Minister Churchill. Foreign Relations of The United States: Diplomatic Papers, 1945, European Advisory Commission, Austria, Germany, Volume III, 740.00119 B.W./4–2545.

2. David Dilks, ed., The Diaries of Sir Alexander Cadogan, 1938–1945 (London: Cassell, 1971), p. 778.

3. Letter written from Harry S. Truman to Sir Winston Churchill, 12 June 1964, CHUR 2/536.61, Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.