Finest Hour 191

Print the Legend

1955. Churchill hosted the first meeting of Commonwealth Prime

January 1, 1970

Finest Hour 191, First Quarter 2021

Page 46

Review by Alastair Stewart

Alastair Stewart is a Scottish public affairs consultant and freelance writer. He is working on a book about Churchill and Scotland.

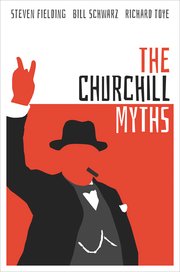

Steven Fielding, Bill Schwarz, and Richard Toye, The Churchill Myths, Oxford University Press, 2020, 224 pages, £20. ISBN 978–0198851967

You would be more successful in counting the stars in the night sky than every Churchill myth. Two twin irritants blight Churchill scholarship: mawkish bon mots, which Churchill never said, or his pantomime bogeyman notoriety. He is only missing the Fu Manchu moustache or perhaps a white cat and a secret lair.

So The Churchill Myths by Steven Fielding, Bill Schwarz and Richard Toye should be a welcome reprieve. The book does not try to answer every charge against Churchill. Nor does it try to dismantle the fetishism of his memory. The authors aim to chart the propagandization of Churchill’s legacy in twentieth-century politics but with mixed results.

2024 International Churchill Conference

No other public figure has so interwoven himself into the cultural and political fabric of countries across the world as Winston Churchill. No other figure is so loved or derided based on half-truths alone. The book charts significant Churchill conjurations in policy and pop culture. But it never quite scratches that itch of a question: why can’t we let Churchill rest in peace?

What is fascinating here is seeing the range of instances of Churchill deployments. The book is a spotter’s guide from the Commons to The Crown. It highlights where Churchill’s reputation evolved beyond itself to become a set of values and finally, an industry. The stereotype has gone one further and influenced campaigns for Brexit and even the rise of Trumpism.

But the authors have pulled at the Gordian Knot. It is a global task to explain every possible reason why Churchill endures as both a cultural symbol and a political prophet. It is disappointing that the book comes in at a mere 162 pages of principal text, for the appetite is very much whet for more. It is really an introduction to how some Churchill factoids came to be, and some more prominent instances where his memory, visage, and spirit were invoked.

Anyone expecting an exhaustive rebuttal against such popular hijackings will be disappointed, and there is a grand spectrum of public maulings to pick from these days. The plurality of Churchills versus the flesh-and-blood man is an ongoing battle. Churchill, as the authors discuss, is more a vessel for modern value debates. The book is full of consistently tight analyses but is slightly too academic to tackle the juiciest of modern Churchill scandals. When everything from white supremacy to genocide and all that is in between are on the table, one needs to be loaded for bear.

The lack of breadth leaves confusing oversights. Brexit is a worthy topic, but the rise in English populism can scarcely be understood without exploring devolution. Churchill is a daily ideological weapon in Scotland, where he is regularly hailed as either a unionist saviour or a blue-blooded fascist of the British state. Both views are paradoxically enabling the cliff-edge push for Scottish independence.

A popular myth abounds that Churchill personally ordered tanks into Glasgow to crush strikers in the 1919 Battle for George Square. The fallacy was recently rebuked when found to have been made the “correct” answer on an official Scottish history test. Churchill is a popular and modern tool to make a point about alleged English oppression. That in itself is indicative of the book’s problem: the title suggests tackling myths. It is more an introduction to understanding the perniciousness of personality cults in England and America.

The book’s premise of understanding Churchill as a prism is culturally illuminating but self-defeating in its political scope. This, of course, presumes one can exist without the other. But Churchill is like Mandela or Gandhi—there came the point when the man split into what we think he is and how his memory is rallied to make a political point.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson—himself an author on Churchill—has dallied in Churchillisms throughout Brexit and in his government’s response to COVID-19. When applied to real life, The Churchill Myths is not the tool to dismantle the political permissibility of Churchillian maxims, clichés, and innuendo. One needs an encyclopaedia to ruin the hagiography and cultism endemic to current policy.

In a quest to find the theory for Churchill’s legacy, the book leaves us wanting more on how to tackle the cancer of ignorance ubiquitous across the Western world. If there is a common thread, it is that many historical figures have become better than they were and worse than we remember. This is a tragedy.

The Churchill Myths is a fascinating, insightful, and often challenging read. It whets the appetite but is too short a work to explain why Churchill, like another British hero, regenerates again and again.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.