Finest Hour 189

A “Villain for All Seasons”

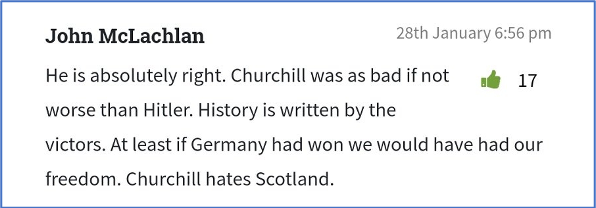

A comment under an article in the nationalist newspaper the National during the controversies about Churchill’s reputation, early in 2019. By the time I took the screenshot, seventeen people had “liked” it.

September 21, 2020

Finest Hour 189, Third Quarter 2020

Page 14

By Gordon J. Barclay

Dr. Gordon J. Barclay is an archaeologist and historian. His most recent book The Fortification of the Firth of Forth 1880–1977: “the Most Powerful Naval fortress in the British Empire” (with Ron Morris) was published in 2019.

The real, complex, and historically important Churchill is increasingly disappearing behind crudely mythologised versions erected by those who wish to defend a political position or a series of values, and those who wish to attack them. On the one hand there is the faultless secular saint; on the other, a villain for all seasons. Oddly, at both extremes, these positions can often be characterised as “nationalistic.” In much of this rhetoric, “Churchill” often seems merely to be a personification of Britain, England, or the Empire for those whose nationalism either idolises or denigrates what they stand or stood for. It appears to have little connection to the real man in the context of the times he lived through.

A particular strand of Scottish nationalism seems to believe that the cause of Scottish independence will be furthered by promoting division and distrust between the Scots and the English. On social media, their rhetoric can cross the line into something like hate speech.

Historical grievances are being resurrected, exaggerated, or just invented. In particular, there are what I have termed the four twentieth-century “military myths,” and it will perhaps come as no surprise to the reader that Churchill features in three of them. It is these three that I discuss here. The fourth, claiming that Scotland suffered disproportionately high casualties in the First World War—between 25% and 28% of enlisted men—has been discredited by Patrick Watt.1

2025 International Churchill Conference

Myth One

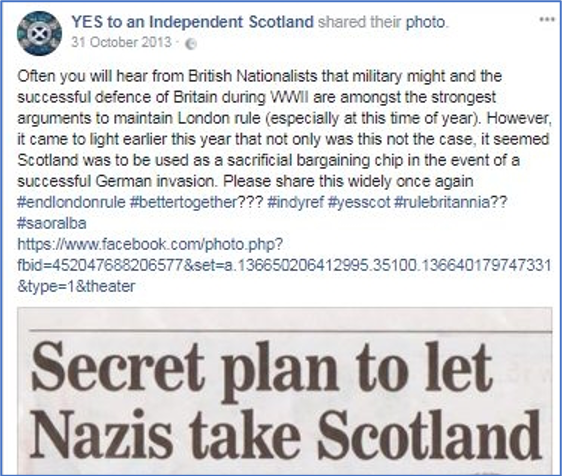

On Sunday, 24 March 2013, in the Mail on Sunday a myth sprang fully formed from the imagination of a journalist, that in 1940 Scotland was to be sacrificed to the Nazis in the event of a German invasion, in order to protect England. The story was picked up and repeated in the Daily Express the next day. Both articles were published in print-only Scottish editions of the respective papers, but the Mail on Sunday article is now available on-line.2

The problem was, that the article named me and my then about-to-be-published book on the anti-invasion defences of Scotland during the Second World War as the source of this “fact.”3 The book and my research suggest no such thing: the myth was created by assigning words to people who did not say them, quoting things from one context as though they were from another, and leaving out much that undermined the story.

Three days before the article was published, the devolved Scottish Government had announced that the referendum on Scottish independence would be held in September 2014. In the atmosphere of increasingly heated debate, the “fact” that in Britain’s “finest hour” Field Marshal Ironside, Churchill, Westminster, and “the English” planned to abandon the Scots to the Nazis was seized upon as a splendid stick with which to beat those campaigning to preserve the Union. At 10 p.m. on 25 March a scan of the Daily Express article was posted on the Facebook page for “Yes to an Independent Scotland” (see image above). This post received almost 1000 “shares” in a short period. Other widely followed bloggers also posted it, and the lie went off round the world.

At that time, I was not active on social media, and it was some time before I became aware that my book had been misrepresented. I started challenging the mythology as soon as I discovered it, but it continues to appear frequently, even now.

Myth Two

In 2014 I wrote an article describing the creation and political use of the “abandon Scotland” myth. Three years later, I was passing long days beside my wife’s hospital bed revising that article, and, while searching for recent occurrences of the first myth, I came upon many social media posts about two others.4 These were, first, that in 1919 “Churchill sent English troops and tanks to George Square, Glasgow to crush a strike,” and, second, that in June 1940, after the end of the Dunkirk evacuation, Churchill “abandoned” or “sacrificed” the men of the 51st Highland Division at St. Valéry-en-Caux “because they were Scots and expendable.”

The first of these two is not as mythological as the “abandon Scotland” story, in that it is, to some extent, based on real events, but the “Battle of George Square” is perhaps the most mythologised event in twentieth-century Scottish history. On Friday, 31 January 1919, a demonstration, part of what was known as the “Forty Hours Strike,” descended into violence between demonstrators and Glasgow police. The army was not “sent to Glasgow” by Churchill, nor even by the government, but was called in by the Sheriff of Lanarkshire as “military aid to the civil power”; he had previously checked that troops would be available. In fact, the War Cabinet had been reminded on the previous day, 30 January, by the commander of the army in the UK, that the government had no legal powers to send troops onto the streets of a British city, unless martial law was declared which in this case, it was not.5

The myth that “Churchill persuaded the Cabinet that troops, machine guns, and tanks should be deployed” seems to have been invented by the Labour politician (and a leader of the Forty Hours Strike) Emanuel Shinwell in his 1973 memoirs I’ve Lived Through It All. Shinwell had blamed “Westminster” in a previous book and would go on to blame the Prime Minister of the time, Lloyd George, in two later books.6 He provided no evidence for any of these accusations, which indeed are contradicted by the War Cabinet minutes.

A century of myth making about the “Battle” means that the mythology is complex. Other elements include claims that:

• All of the troops sent were English. The earliest known date for this claim is 1957, thirty-eight years after the strike. In fact, most of the force was Scots.

• There were troops, tanks, and a howitzer in George Square on 31 January. The troops started arriving late that evening; the tanks arrived three days later; the only howitzer in the Square was a German “trophy” weapon from the war.

• The troops were sent to crush the strike. The strike continued for twelve days after the “Battle.”

The narrative has developed from one of “oppression of the workers by capitalists” into one of an “English invasion.” The reality is that the army was called in by the city’s own authorities; the army decided to use mainly Scottish troops; in such situations the army decides what force it needs and, fearing perhaps a re-run of the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin, took six tanks along, which were not used. Not only was this not an “English invasion,” the majority of War Cabinet members present at the meeting at which it was agreed to provide troops to the Sheriff, if he needed them, were themselves Scots, and the discussion took place in a room where the majority of politicians and civil servants present also were Scots.

The mythology continues to be used as the touchstone of English, Tory, or Westminster oppression, whenever a suitable (or not so suitable) occasion arises. An almost completely mythical version of the event, English troops, tanks in the square and all, continues to appear in Scottish school textbooks.

Myth Three

The third of the myths is more complex. In the period of the “Phoney War” in the west, between September 1939 and May 1940, the British Expeditionary Force was based in northern France, along the frontier with neutral Belgium. It was decided that British formations would be rotated to the French Army, into positions in advance of the Maginot Line, just east of the border with Luxembourg. Here, they would be directly facing the German Army and could gain experience in front-line conditions, for example, undertaking offensive patrolling. Over the winter, nine individual infantry brigades had gained this experience; at the end of the winter, it was decided that a whole division at a time would henceforth be posted to the French on rotation. The 51st (Highland) Division was the first whole division to be sent, late in April 1940. The 51st was a firstline Territorial Army Division comprising nine Scottish infantry battalions and (usually ignored in the narrative of grievance) Royal Artillery, Royal Engineers, and other units, some of which were English. The ancillary force sent with the 51st also contained three English infantry battalions.7

There is no space here to describe their retreat across France. In the end, one-third of the force did manage to escape through Le Havre. The rest retreated towards St. Valéry-en-Caux. Churchill made a calculated decision to keep the 51st in the line with the French, as part of his efforts to keep them in the fight. Was that a useless “sacrifice”? As General de Gaulle said:

…the comradeship in arms experienced on the battlefield of Abbeville in May and June 1940 between the French armoured division which I had the honour to command and the valiant 51st Highland Division under General Fortune played its part in the decision which I took to continue fighting on the side of the Allies unto the end, no matter what the course of events.

The commonly employed narrative of grievance about the 51st is not, however, a subtle consideration of Churchill’s realpolitik, but a series of claims that the 51st was treated worse because they were Scots and therefore expendable. The narrative veers back and forth between “sacrifice” and “abandonment”; the latter is more problematic because it links directly to the frequently made but false assertion that no attempt was made to evacuate the men from St. Valéry. The planned evacuation in more than 200 vessels that had been gathered offshore was made impossible by inadequate communication, fog, and German artillery fire. Some 3,300 men were, however, lifted from a beach at the eastern end of the St. Valéry perimeter. Naturalist Sir Peter Scott, then a naval lieutenant, evacuated injured men from the harbour.8 As in the other military myths, Churchill is assigned personal blame.

The tamer version of this kind of social media post merely states, for example, “Churchill abandoned the fighting Scots of the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division June 1940.” This not only particularises the loss of Scottish troops by ignoring the shared fate of non-Scots, but also promotes the myth of “abandonment,” and implies some sort of deliberate act of malice by Churchill. Unfortunately, this problematic post was put up on the Facebook page of a Scottish veterans’ charity in May 2019. Objections to the post on Facebook were answered, “it is a matter of record that a number of historians believe 51st Div. were abandoned in order to allow the evacuation of 300,000 combatants from Dunkirk.” This is demonstrably untrue: the Dunkirk evacuation, over 200 km away, ended eight days before the surrender at St. Valéry, and the evacuation at Dunkirk was not dependent in any way on the struggle of the 51st. A request to name these “historians” went unanswered, and senior figures in the charity have since defended the decision to keep this post on the site, in the face of objections, as they “have no remit to examine the interpretation of military history” as expressed on their social media feed by their staff. This perhaps indicates how much traction this mythologised version of the past is gaining: a Scottish National Party Member of the Scottish Parliament posted in the following month: “Churchill famously abandoned the Highlanders at St Valéry.”

We should remind ourselves that even this relatively mild statement is untrue and airbrushes from history the loss of non-Scottish troops. But this is only the beginning. Others descend to cruder levels: an office-bearer in an organisation affiliated to the Scottish National Party has recently promoted a newly popular and peculiarly unpleasant variant of the mythology, that Scots and Irish troops were selectively abandoned on the beach at Dunkirk, in favour of Englishmen.

Alternative Facts

I have concentrated on fake history on social media, but much of the same mythologised past appears in newspaper articles, TV documentaries, and even popular and academic histories and school history texts. The promotion of this fake history is an interesting study. Three things strike me. First, it is clear from their basic errors of fact that the majority of the people repeating these myths, especially on social media, have almost no knowledge of the historical events to which they supposedly refer. In relation to the 51st, many people clearly believe that the Division (variously described as a “regiment” or “battalion”) was lost at Dunkirk, having been left behind as the rear guard to allow the “cowardly English” to escape.

Second, I have been struck by the ways in which people are willing to invent new “facts” or fabricate circumstantial detail to support their own version. Thus, if there were troops and tanks in Glasgow, logically it follows that they must have been “sent… to disperse protestors in George Square,” with “orders to shoot to kill,” resulting in “hundreds” dead.

Third, the elaborate mythology is not subject to even the most basic critical analysis. No one asks: could this possibly be true? The most strikingly illogical story that I have come across is that Scottish sailors serving on ships during the Dunkirk evacuation were close to mutiny when the news reached them that the 51st was being “abandoned” at St. Valéry. The observant reader will have noticed the flaw: how could sailors on, at the latest, 4 June 1940 threaten to mutiny about an event that would not happen until 11 June? But logic and sense are not the currency of promoters of “alternative facts.”

The polarisation of politics and society is perhaps seen at its most extreme on social media. It is here that the most blatant rewriting of reality, past and present, is being carried out. Populist nationalist politics, at both national and devolved levels in the UK and elsewhere in the world, thrive in an atmosphere in which trust has been eroded in traditional sources of information and in which expertise and specialist knowledge are denigrated. This is the context in which the myths I have been describing have developed. “Truth” has become no more than “what I want to you to believe.”

Endnotes

1. Patrick Watt, “Manpower, Myth and Memory: Analysing Scotland’s Military Contribution to the Great War,” Journal of Scottish Historical Studies, 39.1, pp. 75–100. So far at least, Churchill has not been blamed.

2. https://www.pressreader.com/ uk/the-scottish-mail-on-sunna/20130324/282106339089564

3. Gordon J. Barclay, If Hitler Comes: Preparing for Invasion, Scotland 1940 (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2013).

4. https://www.academia. edu/35272980/The_birth_and_development_of_a_factoid_2013_17_ the_invention_of_history_in_the_ Scottish_independence_debate

5. See Gordon J. Barclay, “‘Duties in Aid of the Civil Power’: The Deployment of the Army to Glasgow, 31 January to 17 February 1919,” Journal of Scottish Historical Studies (2018), 38.2, pp. 261–92, and Barclay, “‘Churchill Rolled the Tanks into the Crowd’: Mythology and Reality in the Military Deployment to Glasgow in 1919,” Scottish Affairs (2019), 28.1, pp. 32–62.

6. Emanuel Shinwell, Conflict Without Malice (London: Odhams, 1955); I’ve Lived Through It All (London: Gollancz, 1973); Lead with the Left (London: Cassel, 1981); Shinwell Talking (London: Quiller Press, 1984).

7. L. F. Ellis, The War in France and Flanders 1939–1940 (London: HM Stationery Office, 1954), p. 366.

8. Ibid., pp. 291–93, and Peter Scott, In the Eye of the Storm (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1966), pp. 161–63.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.