Finest Hour 187

“Strange Glittering Beings”

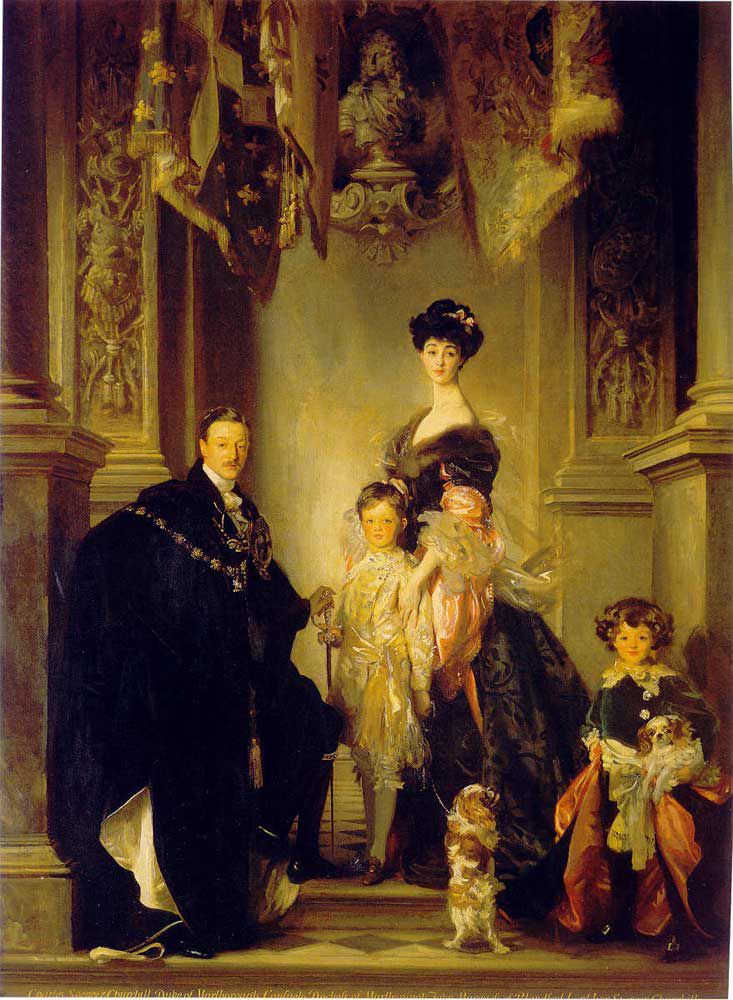

The ninth Duke of Marlborough with his first wife, Consuelo Vanderbilt, and their children, as depicted by John Singer Sargent

July 8, 2020

Finest Hour 187, First Quarter 2020

Page 30

By Hugo Vickers

Hugo Vickers’ biography The Sphinx: The Life of Gladys Deacon, Duchess of Marlborough, was published by Hodder & Stoughton/ Zuleika in January 2020.

It is not beyond the realms of possibility that Winston Churchill could have become the tenth Duke of Marlborough, and thus custodian for life of Blenheim Palace. He was heir presumptive to the title between 1895 and 1897, since at that time his first cousin the ninth Duke had no children, and Winston’s father Lord Randolph Churchill had died in January 1895.

This prospect was evidently of some concern to Frances, Dowager Duchess of Marlborough, a daughter of the third Marquess of Londonderry, though this may have been exaggerated by Consuelo Vanderbilt in her somewhat misleading and self-serving memoirs The Glitter and the Gold. That was the book from which she emerges as the poor, unloved American bride, forced by her mother to marry Sunny, the ninth Duke, in 1895—his only motive to obtain Vanderbilt money to keep Blenheim going. In her book, Consuelo described her husband’s grandmother as “a formidable old lady of the Queen Anne type… [with] large prominent eyes, an aquiline nose, and a God-and-my-right conception of life.”

But according to her biographer, Margaret Elizabeth Forster, the old Duchess was fond of her other grandson, Winston. Yet Consuelo wrote that, no sooner had she married Sunny, the Dowager Duchess admonished the young bride: “Your first duty is to have a child and it must be a son, because it would be intolerable to have that little upstart Winston become Duke. Are you in the family way?”1 Whatever the truth of that, Consuelo obliged by producing “Bert,” the Marquess of Blandford, on 18 September 1897. A younger brother, Ivor, followed in 1898, and Winston was duly side-lined, enabling him to stand as an MP and remain in the House of Commons with significant results.

Winston was one of the many Churchill relations frequently to be found at Blenheim Palace during the ninth Duke’s day. Consuelo liked him: “He struck me as ardent and vital and seemed to have every intention of getting the most out of life, whether in sport, in love, in adventure or in politics,” she wrote.2 She continued that Winston was “the life and soul of the young and brilliant circle that gathered about him at Blenheim.” She contrasted him to her husband: “[Winston’s] conversation was invariably stimulating, and his views on life were not drawn and quartered, as were Marlborough’s, by a sense of self-importance.”3 But there are contradictions. In January 1902 she wrote to Gladys Deacon: “Sunny is still devotedly attentive to Winston’s every remark—a great sign of friendship,” while she was less enthusiastic: “Winston still on the talk—never stops and really it becomes tiring.”4

When Sunny’s marriage to Consuelo was going through a difficult time in January 1900, she having reignited her love for Winthrop Rutherfurd, the man she would have preferred to marry, Sunny was only too happy to head off to the South African War with his cousin Winston and the Yeomanry Volunteers.

In the summer of 1900 General Sir Frederick (Bobs) Roberts VC had three Dukes on his staff—Norfolk, Westminster, and Marlborough. Winston Churchill organised with General Hamilton that Marlborough should accompany him on the march from Bloemfontein to Pretoria. At the beginning of May, both men were part of Hamilton’s column entering the Transvaal, with a chariot and a team of four horses, the wagon secretly stocked with food and alcohol. They reached Pretoria on 5 June, Winston and Sunny galloping in advance of the troops. Winston teased his cousin, saying that if he had not been a Duke, he could have been a jockey. Sunny was livid.

Winston was fond of both Sunny and Consuelo, and, when separation loomed in 1906 (following Consuelo’s departure for Paris with Lord Castlereagh—later Marquess of Londonderry), Winston strove hard to effect a reconciliation. He wrote to his mother from Blenheim: “We are all very miserable here. It is an awful business.”5 But Sunny had had enough—there had been too many affairs—he had suffered enough humiliation—and wanted to end what he called the “false and sordid history” of his marriage. Winston berated Sunny:

Of course I cannot save you from yourself. If you cannot fight & will not make peace you will just be hunted down and butchered. When I think how near we were to a satisfactory settlement it makes me heartsick to see you cast away your last chance of a decent life, by folly & weakness. All you are asked to do is to give up the pleasure of blackguarding your wife. Rather than surrender that, you will immerse yourself in such shame & public hatred that no one will be able to help you any more….

Why on earth can’t you face the situation like a man? Do your best to help Consuelo to have a fair chance in life, under the new conditions, & forget for a moment your petty pride, your shoddy consistency & the damned fools you listen to.

From the bottom of my heart I feel for you in your distraction, but if you muddle this business any longer, compassion is all you will ever get in the world & that only from a few dumbfounded friends.6

A legal separation was granted in January 1907, at which point King Edward VII instructed Lord Knollys to write to Winston to ask him to notify the Duke and Duchess that they “should not come to any dinner or evening party, or private entertainment at which either of their Majesties are expected to be present.”7 Sunny was a Knight of the Garter. He was allowed to attend the Chapters, but he had to leave before luncheon.

Enter Gladys

Gladys Deacon, who was eventually to succeed Consuelo as Duchess of Marlborough, first met Winston at the great Unionist Rally at Blenheim on 10 August 1901. Sir George Lewis, the famous lawyer, stated that she had had nothing to do with the Duke’s separation from Consuelo, though he had been closely interested in her for some years. She and Consuelo were close friends, and it seems to me that Consuelo pushed her towards the Duke, but later chose to blame her for stealing her husband.

ninth Duke of Marlborough

Winston Churchill ran into Gladys in Venice in September 1907 when he shared a gondola with her and described her (and other ladies there) as “strange glittering beings with whom I have little or nothing in common.”8

From Rome in 1908, Gladys wrote to him:

Ah me, dear Winston, you’d said you wd write—& ne’er ere a line. However, I do hear news of you, for the watchful illustrateds bring me good messages of your grand doings. In them I see most respectable looking people bowing & scraping before you, & you looking on with engaging simplicity, good humour & healthy countenance. So I know you are well & successful.9

When he got engaged to Clementine Hozier, she congratulated him from Sils, where she was staying:

Here’s good news & I am not at all surprised to be congratulating you on your engagement.

I prophesized it when in London, feeling your time was ripe.

You spoke of a Lady Blanche something or other with some warmth, so I put her name down as label—It is not she, but I was right in the main = marriage.

May happiness in all her showings abound you & if some picture of the lovely lady / for I was told she is lovely / sd appear in any pictorial, please send it so I too may admire…I love the happy, the busy & you with most particular friendship.10

In old age Gladys retained a less flattering memory of him. She used to compare him to the Italian poet and politician d’Annunzio, of whom she said: “he had spark but not fire.” She added: “In this respect he was like Winston Churchill. Winston…he was not a great man…he had weight, yes, but he was not a gentleman….He liked to lay down the law.” Like Consuelo, Gladys remembered him as a young man with reddish hair, who always had to be the centre of attention. When I said: “He loved Pamela Plowden, didn’t he?” she riposted: “He was in love with his own image, his reflection in the mirror. He took an instant dislike to me. I knew him from top to bottom. He was entirely out for Winston.” She found that if she asked him to do something, he would let her down: “He’d leave you in the boiling pot.” Nor did Gladys have much time for Clementine: “You couldn’t discuss a thing with her. She had no opinions, only convictions.”11

Changing Views

Consuelo would not allow Sunny a divorce until 1920, when she wished to marry the aviator and balloonist, Colonel Jacques Balsan. Meanwhile, Gladys was forced into the role of mistress, staying sometimes in London, but often in Paris, where she had a small apartment on the Quai Voltaire. There exist many letters between Sunny and Gladys, and some of these refer to Winston. In 1915 the Duke was glad to have Winston’s support when it seemed that Consuelo was conspiring against him to prevent him from succeeding the Earl of Jersey as Lord Lieutenant of Oxfordshire. “The C gang” (as Sunny called them) failed, and he was appointed, telling Winston: “The dirty dogs have been downed and may they now come and lick their chops in rage and annoyance.”12

But the Duke and Winston were not always on good terms. Sunny was enraged when Winston introduced the 12 ½ per cent wage increase for skilled workers in February 1918. He ran into Clemmie and she invited him to lunch, but he told Gladys nothing would induce him to accept:

I do not mean to go into their house again—till order reigns in this country—and they have learnt their proper place. That 12 ½ % I can never forgive. It means 150 millions a year more in wages. I wonder what the French would have done to their Minister of Munitions.13

Gladys replied: “WSC is the nucleus of Bolchevism [sic]. He will try to be the Marat of the future. As I’ve told you over & over again, he’s dangerous to your interests.”14

In 1921 Sunny informed Winston that he was finally able to marry Gladys. Winston congratulated him and Sunny replied:

I think that Gladys and I will be happy in our lives together. She is a very remarkable woman and possesses the power of attracting all classes of individuals among the population of Paris to herself, a task by no means easy. Politicians, artists, May Fairies all stream along to see her. The round of social entertainment will soon become intolerable.15

Lady Randolph Churchill died when the Marlboroughs were on honeymoon. Gladys was quick to sympathise with Winston:

I want to tell you how much I grieve with you & how much my thoughts are with you during the first hours of the great sorrow which has come to you….

I was so touched by her wire of good wishes that reached us on our wedding day. It seemed so wonderful to be remembered in one’s happiness by one in such great pain. I wish she cd have known how much we appreciated it!16

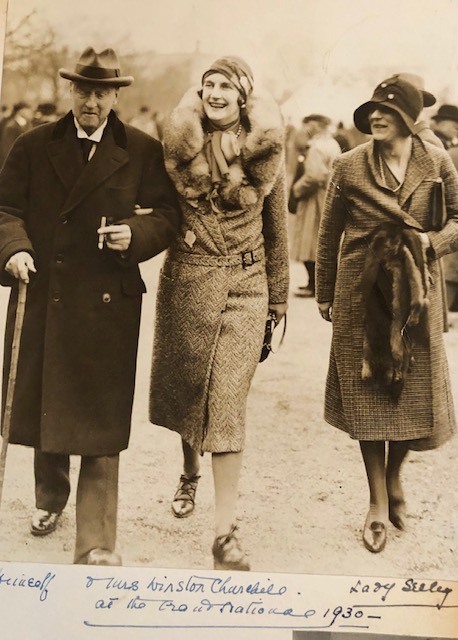

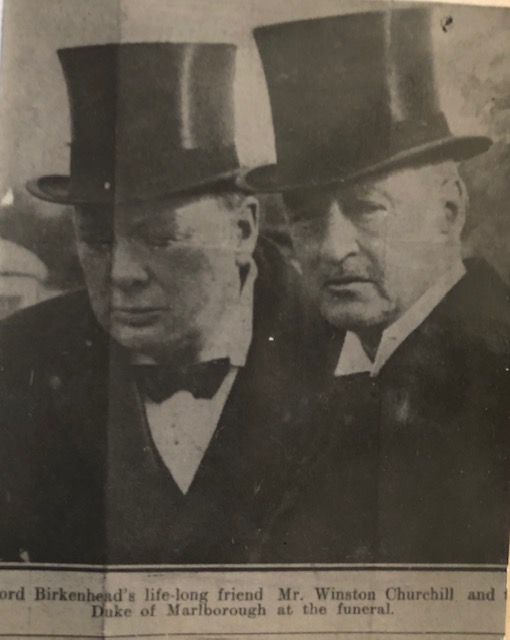

And so from 1921 until 1933, Gladys was chatelaine of Blenheim, and during those years Winston frequently came to stay. She photographed him in house party groups, and with Lady Birkenhead, at Blenheim. She photographed him with Coco Chanel, when Coco was the mistress of Bendor, Duke of Westminster, at Eaton Hall, and she photographed Winston and Sunny together as happy cousins. He attended her Leap Year’s Eve Ball at 7 Carlton House Terrace on 28 February 1928. Fancy dress was the order of the day, and Winston arrived in a toga. Soon afterwards Sunny and Winston were united in grief at the death of their great friend F. E. Smith, Earl of Birkenhead, who died on 30 September 1930.

By this time Sunny and Gladys were far from happy together. In 1931 Sunny left Gladys alone at Blenheim, in favour of life in London, and he concentrated on his racing. He told Winston: “As you may have perceived of late, I have placed more confidence in the performance of quadrupeds than bipeds.”17 During the early years of the 1930s, Winston was not able to stay at Blenheim. Matters deteriorated further. The Duke forced Gladys to leave the palace in May 1933, and furthermore to leave their London home in August that year.

In March 1934 Winston and Gladys met by chance at a dinner at the Mansion House and exchanged a polite “How d’you do.”18

Gathering of Souls

The Duke of Marlborough died aged sixty-two on 30 June, before the divorce papers were filed. Winston wrote a long tribute to him in The Times, describing him as his “oldest and dearest friend.” In it he wrote of Blenheim:

Many happy years were spent by him and his friends amid the spacious fields and noble woodlands of Blenheim Palace. But always there weighed upon him the size and cost of the great house which was the monument of his ancestor’s victories. This he conceived to be almost his first duty in life to preserve and embellish. As the successive crashes of taxation descended upon the Old World it was only by ceaseless care and management, and also frugality, that he was able to discharge his task.19

The ninth Duke was buried in the crypt at Blenheim Palace. There was then a shuffle in the relationships. Consuelo’s son, Lord Blandford, became the tenth Duke and moved from his home in Leicestershire to the Palace. As mother of the Duke, Consuelo was able to enjoy Blenheim and to inspect the improvements undertaken in her absence with the benefit of her money, since the arrangement had been that the Duke received income from the Vanderbilt family from the time of his marriage, until the day he died. Consuelo then helped her son with the necessary improvements to modernise the Palace.

As Winston was on very good terms with Consuelo and also with her son, he was also able to make return visits, and these went on late into his life. When the tenth Duke opened the Palace to the public, he tried to say that Winston had been born in a different room. Winston was not pleased, and told him that if he did so, he would expose him.

During the Second World War, Gladys lived as a recluse in the village of Chacombe, near Banbury. Occasionally she surprised villagers by sending them to the post office with a telegram addressed to the wartime Prime Minister.

Consuelo was the first of the three survivors to die. She died on 6 December 1964 and was buried in Bladon churchyard. Winston died soon afterwards on 24 January 1965, and, after his State Funeral in St Paul’s Cathedral, he joined her at Bladon. Thus he returned to within sight of the palace where he had been born. Gladys lived on, by then enclosed in St Andrew’s Hospital, Northampton. She died there, aged ninety-six, on 13 October 1977 and was buried in Chacombe churchyard.

Endnotes

1. Consuelo Vanderbilt Balsan, The Glitter and the Gold (New York: Harper, 1952), pp. 71–72.

2. Ibid., p. 70.

3. Ibid., p. 131.

4. Consuelo to Gladys Deacon, 6 January 1902, Blenheim Palace Archives.

5. Randolph S. Churchill, ed., The Churchill Documents, volume III, Early Years in Politics, 1901–1907 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2008), p. 588.

6. Winston S. Churchill (WSC) to Duke of Marlborough, 4 January 1907, CHAR 1/65/1, Churchill Archives, Cambridge.

7. Philip Magnus, King Edward VII (New York: Dutton, 1964), pp. 405–06.

8. Randolph S. Churchill, ed., The Churchill Documents, volume IV, Minister of the Crown, 1907–1911 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2008), p. 680.

9. Gladys to WSC, 2 January 1908, CHAR 1/72/5–6.

10. Gladys to WSC, (undated) but August 1908, CHAR 1/76.

11. Hugo Vickers, The Sphinx: The Life of Gladys Deacon, Duchess of Marlborough (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 2020), pp. 8, 132, and 220. See also Hugo Vickers, Gladys, Duchess of Marlborough (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1979), p. 114.

12. Martin Gilbert, ed., The Churchill Documents, volume VII, “The Escaped Scapegoat,” May 1915- December 1916 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2008), p. 1080.

13. Marlborough to Gladys, 5 February 1918, Blenheim Palace Archives.

14. Gladys to Marlborough, February 1918, Blenheim Palace Archives.

15. Marlborough to WSC, 7 June 1921, CHAR 1/138/41.

16. Gladys to WSC, 3 July 1921, CHAR 1/143/178.

17. Marlborough to WSC, 29 May 1932, CHAR 2/573 A-B.

18. Martin S. Gilbert, The Churchill Documents, volume XII, The Wilderness Years, 1929–1935 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2009), p. 736.

19. Winston Spencer-Churchill and C. C. Martindale, Charles, IXth Duke of Marlborough, K.G. (London: Burns, Oates and Washbourne, 1934), p. 7.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.