Finest Hour 187

Betrothal at Blenheim

The Seventh Duke of Marlborough as caricatured by “Spy”

July 22, 2020

Finest Hour 187, First Quarter 2020

Page 26

By Mary Soames

This text is taken from Mary Soames’s 1979 biography of her mother Clementine Churchill: The Biography of a Marriage and is reprinted with permission.

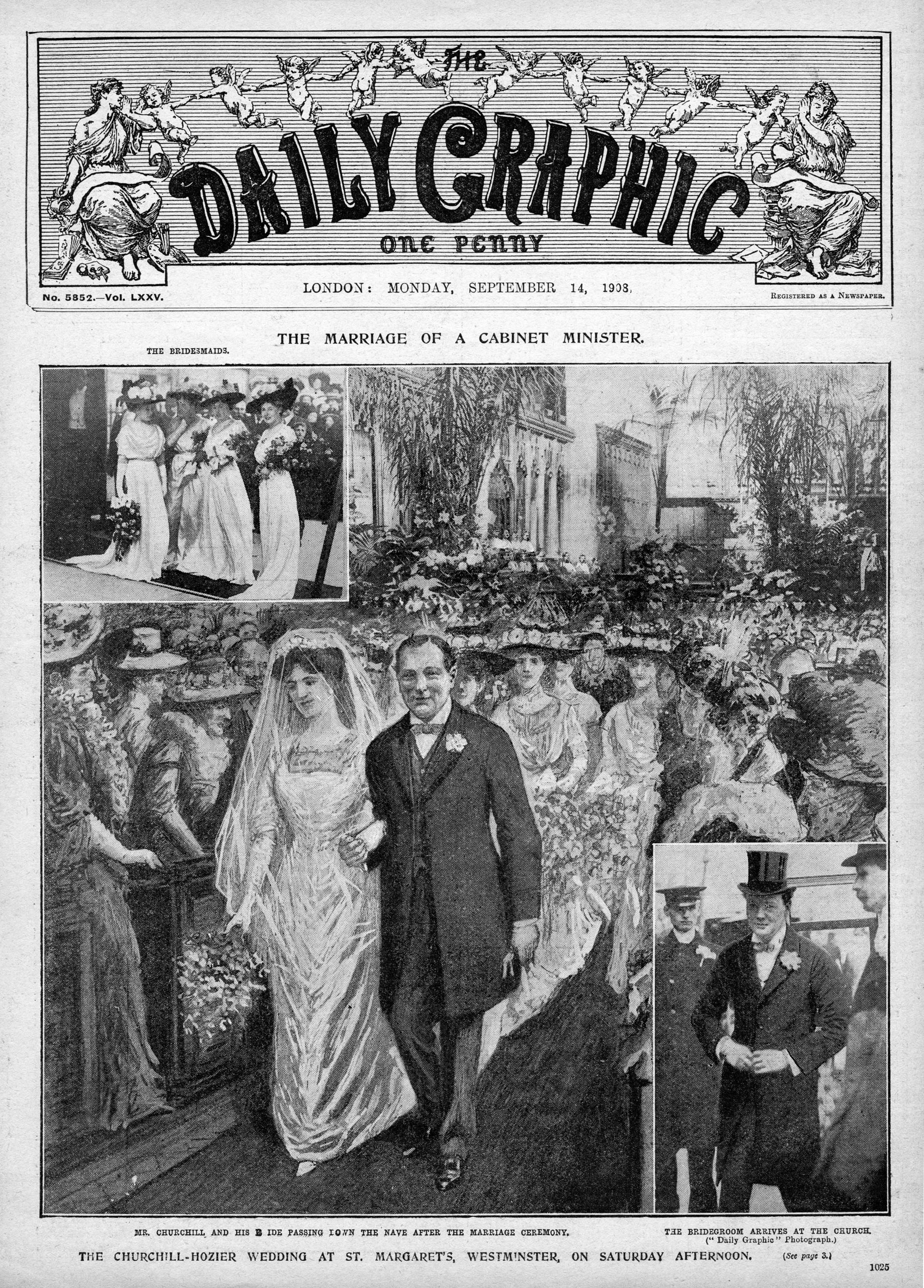

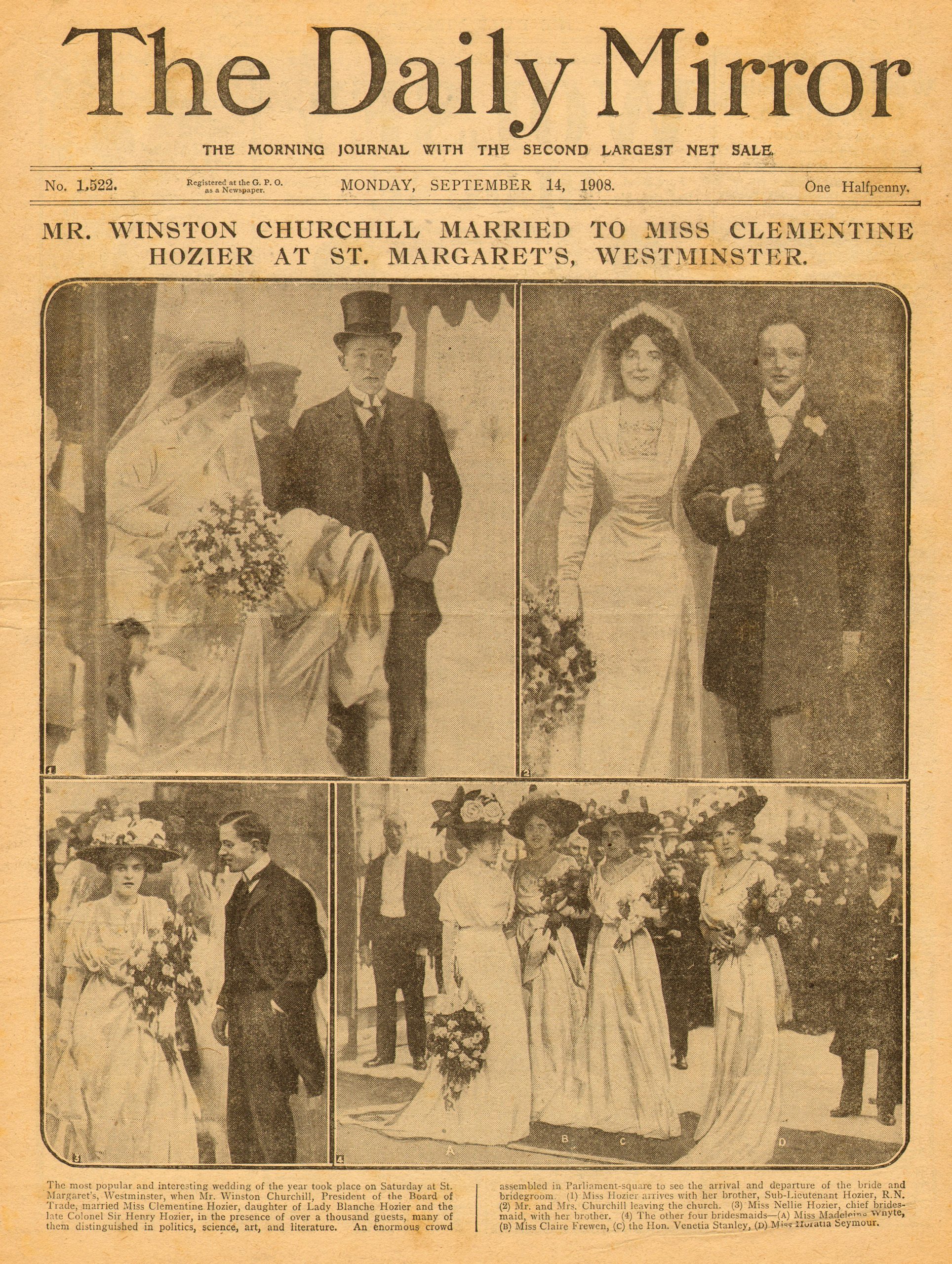

The youngest child of Winston and Clementine Churchill recounts how her parents became engaged at the time her father was President of the Board of Trade.

During the months of June and July [1908, Winston] and Clementine met several times, but as unmarried girls did not in those days lunch or dine alone with men, they met in the main only on social occasions. Clementine was by now deeply in love, and in an agony lest their growing friendship should be remarked upon. Such was her anxiety on this count that when Winston invited her to a garden party he was giving in the gardens of Gwdyr House (then the Board of Trade) she declined to go. Presumably their closest family must have been aware that something was brewing, but their discretion was complete. More than most girls Clementine could keep her own counsel, so now at this crucial moment of her life even her close friends were not aware of her feelings.

The parliamentary summer recess was soon imminent, and both Winston and Clementine were committed to prearranged visits, but they planned to meet at Salisbury Hall in the middle of August. In the interval, Clementine went to stay with Mrs. Godfrey Baring at Nubia House in Cowes. She took part in the round of balls and entertainments, but she was a somewhat distracted guest, as her thoughts were elsewhere.

Winston was staying with his cousin Freddie Guest, and his American wife, Amy Phipps, at Burley Hall, near Oakham, a house the Guests had rented. During the night of August 6, soon after everyone had gone to bed, a fire broke out, and a whole wing of the house was burned to the ground by daybreak. Rumors fly fast, and Clementine’s heart turned over when she heard a garbled account of the disaster. She knew Winston to be one of the house party, and first reports were alarming about loss and injury. Fortunately The Times put her out of her misery: The damage had been great, but no loss of life or injury had occurred. Unable to contain her grief and joy, she rushed to the local post office and sent a telegram to Winston.

On August 7, he wrote her a long letter from Nuneham Park (Sir Lewis and Lady Harcourt’s house, where some of the Burley Hall party had taken refuge), in which a lively account of the fire took third place to an alteration in plans for the visit to Salisbury Hall, and an account of his broth er Jack’s marriage to Lady Gwendeline Bertie (daughter of the Earl of Abingdon), which had taken place at Abingdon on August 4.

The alteration in plans consisted of interposing a two-day visit to Blenheim Palace before going to Salisbury Hall. Winston had arranged everything with his cousin Sunny, the [ninth] Duke of Marlborough, who invited Clementine at Winston’s urgent behest. Clementine jibbed at this, to her, somewhat alarming suggestion but allowed herself to be persuaded by Winston’s assurance that “Sunny wants us all to come, & my Mother will look after you—& so will I. I want so much to show you that beautiful place & in its garden we shall find lots of places to talk in, & lot of things to talk about.”

The following evening, August 8, Clementine wrote from Cowes:

I was so glad to get your delightful letter this morning. I retired with it into the garden, but for a long time before opening it I amused myself by wondering what would be inside. I have been able to think of nothing but the fire & the terrible danger you have been in—The first news I heard was a rumour that the house was burntdown—That was all—My dear heart stood still with terror. All the same I did not need that horrible emotion to ‘jog my memory’.

Please do not think there is any real reason for my not at first wanting to go to Blenheim. It was only a sudden access of shyness….

Another reason for her hesitation was that Clementine was down to her last laundered and starched dress and, having no personal maid, she would have to make this one last the unexpected visit. Clementine had evidently telegraphed Winston that same Saturday morning to acquiesce in the plans to go to Blenheim. Winston hastened to reassure her that there would be no large party, and to introduce her, as it were ahead of the event, to his first cousin, the Duke: “I hope you will like my friend, & fascinate him with those strange mysterious eyes of yours, whose secret I have been trying so hard to learn….”

Throughout his life Winston was a frequent visitor to Blenheim. It was in a special sense his home: there he was born; there he became engaged; there he spent the first few days of his honeymoon. Later, when Winston wrote his splendid life of the great Duke of Marlborough, Blenheim epitomized for him the triumphs and magnificence of England and of his hero. And so it seemed most right and fitting that in the end he should have wished to return there—to Bladon, and the little churchyard just outside the park—to lie close to his parents and kinsfolk.

It seems certain from his letters that Winston had determined to ask Clementine to be his wife. He had taken his cousin, the Duke, into his confidence, and the Blenheim visit was undoubtedly arranged so that he could propose to this beautiful girl with whom he was so deeply in love in a setting which combined the romantic with the heroic, and where he felt so strongly the ties of family and friendship.

In the train traveling between Cowes and Blenheim, Clementine wrote to her mother, who was in London: “I shall get to Oxford at 5.20 where I shall be met by motor. I feel dreadfully shy & retired….I will write to you tomorrow morning from Blenheim. I shall see 2 of Winston’s greatest friends there—the Duke and F. E. Smith.”

The somewhat hastily arranged house party gathered at Blenheim Palace on Monday, August 10. It was, as promised, a small one. Winston came with his mother, and a Private Secretary from the Board of Trade (for affairs of state must not be neglected, even at such an hour). The F. E. Smiths were the only other guests.

Before retiring to bed on the Monday evening, Winston made an assignation with Clementine to walk in the rose garden the following morning after breakfast. Appearing punctually at breakfast was never at any time in his life one of Winston’s more pronounced qualities; even on this day of days he was late.

Clementine came downstairs with characteristic punctuality, and was much discomfited by Winston’s non-appearance. While she was eating breakfast, she seriously turned over in her mind the possibility of returning then and there to London. The Duke observed that Clementine was much put out, and took charge of the situation. He despatched a sharp, cousinly note upstairs to Winston and, deploying his utmost charm, suggested to Clementine that he should take her for a drive in his buggy. He whirled her round the estate for about half an hour, and upon their return there was the dilatory Winston anxiously scanning the horizon.

During the course of the late afternoon, Winston and Clementine went for a walk in the garden; overtaken by a torrential rainstorm, they took refuge in a little Greek temple [the Temple of Diana], which looks out over the great lake. Here Winston declared his love, and asked Clementine to marry him. When in due course, and the rain shower being over, they emerged from the temple— they were betrothed.

Clementine had enjoined absolute secrecy upon Winston until she had been to London to tell her mother their great news, and to seek her formal consent. But as they drew near the house they met the Duke and his other guests gathered on the lawn; whereupon Winston’s triumph and joy were too much for him to contain—he started running across the lawn waving his arms with excitement, and, despite his promise to the contrary, told his assembled friends and relations his glorious tidings.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.