Finest Hour 186

Churchill and the Nuclear Cold War

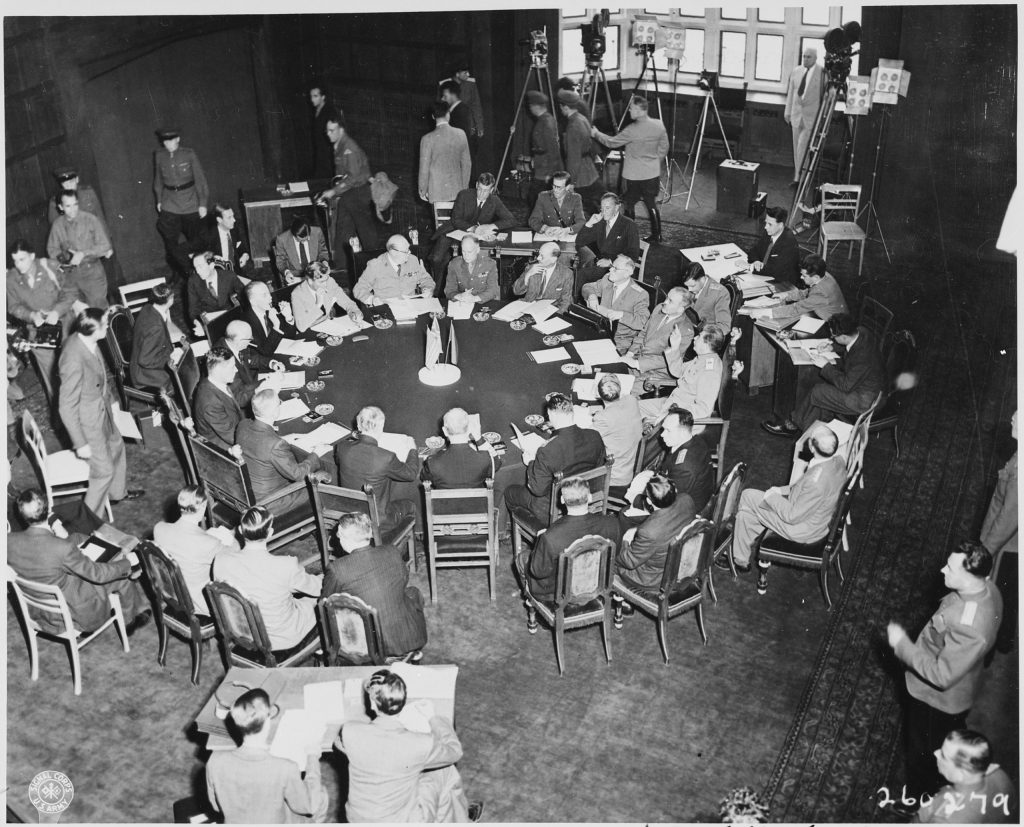

A sitting of the Potsdam Conference in Berlin, July 1945

February 19, 2020

Finest Hour 186, Fourth Quarter 2019

Page 23

By Kevin Ruane

Kevin Ruane is Professor of Modern History at Canterbury Christ Church University, an Archives By-Fellow of Churchill College, Cambridge, and author of Churchill and the Bomb in War and Cold War (Bloomsbury, 2016), a BBC History “Book of the Year.”

In 2013, a short fragment from a British Royal Family home-movie came to light. Dating from October 1952, the silent footage shows the young Queen Elizabeth II enjoying a family fishing expedition at Balmoral in Scotland. Also prominent is the unmistakable figure of Winston Churchill, returned as Britain’s Prime Minister the year before; he can be seen sitting on the riverbank chatting to Prince Charles.1 He is relaxed, but he is not off-duty. His thoughts, we now know, were focused on the Montebello Islands, a barren outpost of the Commonwealth eighty miles off the north-west coast of Australia. It was there that the United Kingdom’s first atomic bomb, a plutonium weapon, was about to be tested.

Much rested on the success of “Hurricane,” as the test was codenamed, not least the future of Britain’s independent nuclear deterrent. “Pop or flop?” an anxious Churchill asked his scientific experts as the test neared. “Pop” came the reassuring reply.2 And pop it was. On 3 October 1952, Churchill, still at Balmoral, learned that the “Hurricane” device had detonated with a destructiveness equivalent to twenty-five kilotons of TNT, a yield which surpassed the A-bombs used against Japan in 1945.

What, one wonders, did Churchill say to his young Queen when he briefed her later that day? How did this Victorian cavalry officer, trained in horse, sword, and pistol process the fact that now, at the dawn of a second Elizabethan Age, he had at his disposal a weapon which drew on the same energy that fuelled the stars of the night sky?

What occurs between monarchs and prime ministers is a closely guarded secret, but we may still speculate. Aside from expressing pride in his country’s scientific-technological achievement, Churchill probably spoke of the increased national security an A-bomb would provide in a dangerous Cold War world. In prestige terms, he could rightly claim that the bomb bestowed on the United Kingdom a power-status matched only by the other members of the old wartime Big Three, the already nuclear-armed America and Russia. More sombrely, he may have harkened back to 1945, to Hiroshima and Nagasaki; two cities, two bombs, two flashes, and 100,000 dead in an instant. If, in addition, he thought to himself, “at last,” that would be understandable. He had waited a long time for this moment.

The Manhattan Project

Eleven years earlier, in August 1941, when his country was in the coils of a war for survival, Churchill had given the go-ahead to a top-secret effort to build a super-weapon, an atomic bomb. A convergence of factors led him to approve “Tube Alloys,” the codename for the endeavour: his rich scientific imagination, fanned by a love of science fiction; his passion for the application of science to warfare; and above all, the dread prospect of an A-bomb in Adolf Hitler’s hands should Nazi scientists win the battle of the laboratories.3

Following the USA’s entry into the Second World War in December 1941, Britain’s pioneering work on Tube Alloys became subsumed into the American bomb programme, the scientific-industrial giant known as the Manhattan Project. Churchill, however, fought hard to protect Britain’s atomic rights. In the Quebec Agreement of August 1943, for example, he secured US acceptance that the combat use of any new weapon required US-UK “mutual consent.”4 Two years on, in June 1945, with an A-bomb very close to realization, Harry Truman (who had succeeded to the presidency on Roosevelt’s death) duly sought Churchill’s consent to deploy the bomb against Japan, the only member of the Axis still fighting.

Back in the 1920s, Churchill had made a number of predictions about the impact of science on warfare: “Might not a bomb no bigger than an orange be found to possess a secret power…to blast a township at a stroke?” Would a military leader in another “world-agony” be able to ‘extinguish…London or Paris, Tokio [sic] or San Francisco, by pressing a button, or putting his initials neatly at the bottom of a piece of foolscap?”5 On 2 July 1945, Churchill lived out his premonition. On a piece of foolscap referring to Truman’s request for UK consent to use the atomic bomb on Japan, Churchill wrote, neatly, an approving “W.S.C.”6

A fortnight later, the Manhattan Project climaxed with the successful test of a plutonium device near Alamogordo, New Mexico. Codenamed “Trinity”, the test not only marked the birth of the nuclear age but sped the war with Japan towards its endgame. On 6 August, a uranium bomb destroyed Hiroshima. On 9 August, a plutonium bomb devastated Nagasaki. On 14 August, Japan surrendered unconditionally.

By then, of course, Churchill was no longer Prime Minister: the result of the British General Election, declared on 26 July, confirmed a landslide victory for Labour. Churchill, however, was determined that his role in the atomic drama should be recognised. “The decision to use the atomic bomb,” he told the House of Commons on 16 August, “was taken by President Truman and myself.”7

Nuclear Diplomacy

Churchill had been at Potsdam in July 1945 for the final Big Three conference of the war when he learned from the Americans that the “Trinity” test had exceeded all expectations. In terms of the war with Japan, this news changed nothing: Anglo-American agreement to use the bomb had already been reached. In contrast, in terms of Churchill’s approach to the USSR, “Trinity” changed everything.

Whenever Churchill looked at the map of Europe as it stood on 8 May 1945, Victory in Europe Day, his relief at the defeat of Nazi Germany was tempered by grave concern about Soviet intentions. The Red Army physically occupied Eastern Europe, the Balkans, half of Germany and the Baltic States with no sign that the Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin, intended honouring earlier pledges to permit free and democratic elections in countries “liberated” by his armed forces. For Churchill, this was a deeply distressing development. Britain went to war in 1939 not just for the sake of Poland but to save Europe from the tyranny of the right, Nazism. Now, with Hitler’s Third Reich in ruins, the tyranny of the left, Soviet communism, appeared dominant throughout the eastern half of the continent. And what of the western half? Would Stalin rest content or seek to expand towards the English Channel?

This brings us back to Potsdam. Briefed by Truman about the Trinity test, Churchill instantly recognised the A-bomb’s diplomatic value. The United States had “the power to mould the world,” he maintained.8 The A-bomb might even be the lever to prise Eastern Europe from Stalin’s grip. “Churchill said that we now had something in our hands which would redress the balance with the Russians!” Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke recorded in his diary. Churchill wanted to say to Stalin that “if you insist on doing this or that, well we can just blot out Moscow, then Stalingrad, then Kiev, then Kuibyshev, Karhov…Sebastopol. And now where are the Russians!!!”9

“Monstrous Child”

As it transpired, Churchill was given no time to factor the A-bomb into his Russia policy before he lost office. But there is ample evidence as to what that policy would have involved. The day after Hiroshima, Churchill lunched with Lord Camrose. “Churchill is of the opinion that, with the manufacture of this bomb in their hands, America can dominate the world for the next five years,” Camrose wrote afterwards. “If he had continued in office, he is of the opinion that he could have persuaded the American Government to use this power to restrain the Russians.” There must be a showdown with Stalin, Churchill insisted, with the Soviet leader given an ultimatum: either abide by democratic norms in Eastern Europe or face punishing atomic consequences.10

For the next five years—the period when the Cold War was joined—the need for a nuclear-infused diplomatic showdown with the Russians was Churchill’s repeatedly (if privately) expressed conviction. Accepting that politicians in opposition are freer to express themselves than those in power, the consistency and vehemence with which Churchill spoke of a showdown, before the USSR got an A-bomb of its own, points to some seriousness of intent.

One example of Churchill’s showdown mind-set must stand for the many that exist. In November 1947, he met the Canadian leader William Mackenzie King in London. When Stalin cropped up in conversation, the “gleam” in Churchill’s “eyes was like fire,” King noted in his diary. If the Soviet dictator refused to accept an all-European settlement rooted in Western democratic values, Churchill proposed to tell him directly that “the nations that have fought the last war for freedom, have had enough of this war of nerves and intimidation,” this so-called Cold War. “If you do not agree to pull out of Poland and Eastern Europe here and now, within so many days, we will attack Moscow and your other cities and destroy them with atomic bombs from the air.”11

In the event, the Truman administration proved wary about employing its atomic monopoly in so threatening a manner, a hesitancy that frustrated Churchill. But then around 1949–1950, something unexpected occurred: Churchill, the man of Fulton and the Iron Curtain, the archetypal Cold Warrior, began to reinvent himself as a Cold War peacemaker. The transition was gradual, but by 1954 he was a fully-fledged advocate of détente.

The shift in Churchill’s outlook dates from September 1949 when the news broke that the USSR had tested its first atomic bomb. Like many in the West, Churchill was unnerved by the sudden ending of the American atomic monopoly. In January 1950, the Truman administration announced its response: the United States would build the “super,” a hydrogen weapon. With a predicted power up to 1,000 times greater than the A-bombs used against Japan, the thermo-nuclear H-bomb was not the next rung on the ladder of escalation in the arms race, it was the top rung itself. Previously, Churchill had looked on the atomic bomb as “the perfected means of human destruction.” Now, “its monstrous child, the hydrogen bomb,” was poised to eclipse it.12

New Priority

Against this troubled backdrop, Churchill called for an East-West summit in the hope of reducing Cold War tensions before they spiralled into a Hot (nuclear) War. Put forward in the middle of the February 1950 UK General Election campaign, Churchill’s proposal was dismissed by Labour as a cynical attempt to win votes by playing on popular nuclear anxieties. In truth, Churchill’s summitry was inspired by alarm over the Soviet A-bomb, unease at the prospect of the hydrogen bomb, and fear for the fate of the United Kingdom in any nuclearized general war.

Labour won the 1950 election but by so small a margin that another poll beckoned. It took place in October 1951. This time the Conservatives secured an overall majority of twenty-six, modest but sufficient for Churchill, approaching 77 years of age, to reclaim the premiership. A year on, Churchill was at Balmoral awaiting news from Montebello. When the success of “Hurricane” was finally confirmed, he became the first British Prime Minister in history to have a nuclear weapon at his disposal.

The nuclear club now numbered three, the USA, USSR and UK. But it was not a club of equals. In August 1953, Britain’s achievement was put into perspective when the USSR announced that it had become the world’s first thermo-nuclear power. “We were now as far from the age of the atomic bomb as the atomic bomb itself from the bow and arrow,” Churchill lamented.13 Should Britain ever fall victim to Soviet H-bomb bombardment, he feared that “all we hold dear, ourselves, our families and our treasures” would be immolated. “[A]nd even if some of us temporarily survive in some deep cellar under mounds of flaming and contaminated rubble, there will be nothing left to do but to take a pill to end it all.”14

Thanks to the H-bomb, by 1954 Churchill’s transformation into a Cold War peacemaker was complete. As long as Cold War tensions persisted, so did the danger of Hot War and thermo-nuclear conflict. Détente, in consequence, became Churchill’s overriding priority, with the convening of a summit an essential first step in that direction.

Events added urgency to Churchill’s quest. In February 1954, US President Dwight D. Eisenhower confirmed that America had in fact been a thermo-nuclear power for some time and already possessed deliverable hydrogen bombs. The following month came press reports of an American thermo-nuclear test in the Pacific. Codenamed “Bravo,” the test produced a staggering fifteen-megaton explosion. Aside from the enormity of the blast, Bravo gave Churchill something else to worry about: nuclear fall-out, airborne radioactive “death clouds.” The danger from fall-out was acute for Britain. As Churchill reminded Eisenhower, the current generation of Soviet bombers had the operational range to reach the UK but not the USA. Hence, if another war came, it would be Britain and Western Europe, not America, that faced the prospect of total devastation.15

With his thoughts “almost entirely thermo-nuclear,” Churchill devoted much of his remaining time in office to bringing about a summit.16 Stalin died in 1953, and his successors were quick to employ the language of détente. Eisenhower, however, repeatedly made clear to Churchill that he wanted communist deeds, not words of peace before he would consider attending a summit. The Russians, meanwhile, sceptical that Churchill had truly abandoned his long-standing anti-communist outlook, treated his pacific overtures with suspicion. Consequently, when Churchill stepped down as Prime Minister in April 1955, he did so with his summitry ambition unfulfilled.

Getting MAD

Churchill was disappointed, naturally, but he was not without hope for the future. A rarely noticed feature of his final phase as Prime Minister was his emergence as a pioneer of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD). The concept of MAD—the idea that if both sides in the nuclearized Cold War possessed the ability to destroy one another in equal measure, then neither would bother trying to do so and a general, if uneasy, peace would prevail—is most often associated with the nuclear arms race from the 1960s onwards. Churchill, however, got “MAD” a good decade earlier.

Addressing parliament in November 1953, Churchill said he was looking forward to a time when “the advance of destructive weapons enables everyone to kill everybody else,” because then “nobody will want to kill anyone at all.”17 In March 1955, in his last speech before relinquishing the premiership, he told the Commons that if both Cold War blocs enjoyed comparable levels of destructive capacity, then by a “sublime irony…safety will be the sturdy child of terror, and survival the twin brother of annihilation.”18

Does it diminish Churchill the nuclear peacemaker that he had once been a would-be atomic warrior? Hardly. What his personal nuclear journey demonstrates is his ability to react creatively to the challenges of a dangerous international situation, while his later “MAD”-ness is testimony to his capacity for visionary thinking on the greatest life-and-death issue of the Cold War.

Endnotes

1. Chartwell Bulletin, No. 58 (2013).

2. Cabinet conclusions, CC(52)15, 11 February 1952, UK National Archives (UKNA), London, CAB195/10.

3. Churchill to Ismay, 30 August 1941, UKNA, PREM3/139/8A.

4. Quebec Agreement, August 1943, www.atomicarchive.com.

5. Churchill in Kevin Ruane, Churchill and the Bomb in War and Cold War (London: Bloomsbury), pp. 12 and 117.

6. Churchill annotation, 2 July 1945, UKNA, PREM3/139/8A/11A.

7. Hansard, House of Commons Debates (HCD), 5th Series, Vol. 413, column 79, 16 August 1945.

8. Churchill, 23 July 1945, in Lord Moran, Winston Churchill: The Struggle for Survival (London: Constable, 1966), pp. 280–81.

9. Brooke, 23 July 1945, in Alex Danchev and Daniel Todman, eds., The War Diaries of Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke, 1939–1945 (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2001), pp. 709–10.

10. Camrose, 7 August 1945, in Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, Volume VIII, Never Despair, 1945–1965 (London: Heinemann, 1988), p. 119.

11. King diary, 26–27 November 1947, Canadian government online Library and Archives website.

12. “Epilogue, 1945–1957,” in Winston Churchill, The Second World War: Abridged One-Volume Edition (London: Cassell, 1959), p. 963.

13. Churchill, August 1953, in John Colville, The Fringes of Power: Downing Street Diaries, 1940–1955 (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1985), pp. 675–76.

14. Churchill, 5 December 1953, Eisenhower Presidential Library, Abilene, DDE Papers, International Meetings Series, Box 1.

15. Churchill to Eisenhower, 9 March 1954, UKNA, PREM11/1074.

16. Churchill, 26 June 1954, in Moran, Churchill, p. 562.

17. HCD, Vol. 520, columns 28–31, 3 November 1953.

18. HCD, Vol. 537, columns 1893–1905, 1 March 1955.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.