Finest Hour 185

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – Overstretched Air Chief Marshal

August 21, 2019

Finest Hour 185, Third Quarter 2019

Page 46

Review by W. Mark Hamilton

W. Mark Hamilton is author of The Nation and the Navy: Methods and Organization of British Navalist Propaganda, 1889–1914 (1986).

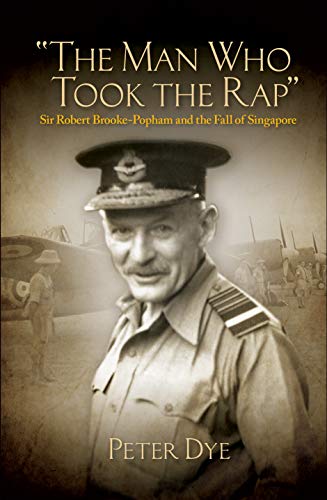

Peter Dye, The Man Who Took the Rap: Sir Robert BrookePopham and the Fall of Singapore, Naval Institute Press, 2018, 410 pages, £43.50/$44.95. ISBN 978–1682473580

For Winston Churchill, the fall and surrender of Singapore to Japan in February 1942 was an emotional scar he would carry his entire life, much like Gallipoli. He called the fall of the “Gibraltar of the East” the “largest capitulation in British military history.” In retrospect, we know it ultimately signaled the end of Great Britain’s Asian Empire.

Historian Peter Dye has written the first biography of a key figure in the Singapore story—Air Chief Marshal Sir Henry Robert Moore Brooke-Popham. It was BrookePopham who took the ultimate blame for Churchill’s Singapore nightmare. The goal of this biography is to provide a more balanced view of Brooke-Popham’s life and his many contributions to the defence of the British Empire.

Early chapters reveal BrookePopham’s pioneering work to enhance British air power in the Royal Flying Corps before and during the First World War. A man of high intellect, he was hard-working and an excellent writer. Dye says Brooke-Popham found a keen sense of purpose when the RFC became the Royal Air Force (RAF) in 1918.

The 1911–1920 Cairo-Baghdad air route can be attributed to Brooke-Popham’s work. Creating new aviation links was part of Britain’s effort to unify the Empire and meet the demand for reliable communications, a demand that extended to the Far East. BrookePopham held the Iraq Mandate Command in 1928, a period of Arab unrest, when Britain used airpower as a tool of suppression and control. In later years, the rising RAF air marshal worked to improve Britain’s tense relations with Egypt through the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936. Anthony Eden, British foreign secretary and later prime minister, gave Brooke-Popham full credit and praise for progress made with Egypt on a variety of contentious issues.

As early as 1921, discussions had commenced in London on the future defence of the island fortress of Singapore, located on the southern tip of the Malay peninsula. Anglo-Japanese relations had deteriorated since the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902. Japanese military power had greatly increased, especially with the defeat of the Imperial Russian Navy in 1905, and strong pressure on Great Britain from the United States to reduce Anglo-Japanese cooperation. “Navalism” was on the rise as Japan looked with envy on the resource-rich European colonies in the Pacific and the Far East.

Neither Churchill nor his military commanders really understood the impending Japanese threat to Britain’s Far-Eastern Empire and its vital naval fortification at Singapore. Churchill thought it “irrational” for Japan to attack Great Britain, and he had serious doubts about Japanese military capability, much as he had about Ottoman fighting abilities before the First World War. According to Dye, Brooke-Popham shared identical views. The British strategy was to send out the needed reinforcements to Singapore if and when a Japanese attack occurred rather than to keep a permanent force in place. No one imagined then that Britain would be facing a hostile Germany and Italy when Japan made good on its threats to Singapore.

During the build-up to the Second World War from 1937 until 1939, Brooke-Popham served as governor of the Kenya colony. London chose him because it wanted a governor with military experience. Italy had invaded Abyssinia (Ethiopia), which shares Kenya’s northern border. Brooke-Popham’s service was adequate but not distinguished, and he rejoined the RAF with the outbreak of the war in Europe.

Journalists described a frail and tired Brooke-Popham, who, at the then rather advanced age of sixty-two, was made Commander-in-Chief of the Far East Command, an appointment confirmed at an October 1940 luncheon with Churchill. The appointment came as a surprise to Brooke-Popham and other senior military commanders, since Britain’s relationship with Imperial Japan was worsening and Brooke-Popham was not considered a wartime commander. To add to the dire situation, Japan received captured top-secret British intelligence from her German ally regarding defence of Britain’s Asian colonies, which revealed that Churchill’s first priority was the war in Europe. Presciently, Brooke-Popham, with Churchill’s approval, drafted a plan to meet a Japanese land attack on Malaya, but “Operation Matador” was never fully implemented or executed, Dye writes. Ultimately Japan did attack Singapore from the land side.

Dye creates a compelling narrative of events leading up to the fall of Singapore—and the downfall of Brooke-Popham’s career. Despite displaying public optimism about meeting the Japanese threat, Brooke-Popham revealed his concerns in private letters to his much younger wife, Opal. He shared his thoughts with his American and Dutch Pacific allies, who also feared a Japanese attack on their Asian possessions. Brooke-Popham was provided with a very small staff, and his requests for more modern armaments fell on deaf ears as London gave higher priority to the fighting in Europe and North Africa.

GET OUR BULLETIN

Brooke-Popham’s relations with the press were poor, especially with American journalists, and there was considerable backbiting among the British resident officials. Life magazine published a July 1941 cover story describing him as “exquisitely English—tough, tactful, thoughtful, and fond of flowers.” Though he met his social and official duties, Brooke-Popham did himself no favors by earning a reputation for napping in the corner after lengthy formal dinners, which became the talk of Singapore colonial society.

Increasingly critical reports reached Churchill and the London Cabinet. Australia was especially nervous and displeased with British defensive efforts. When British Minister of Information Duff Cooper was dispatched to the Far East to investigate, BrookePopham was justifiably worried about what Duff Cooper would tell London. Cooper was not pleased. In November 1941, Churchill replaced Brooke-Popham, thanking him for his nearly one year of service as Commander-in-Chief of the Far East Command, and offering him a baronetcy—which was never bestowed. Before Brooke-Popham reached Britain by passenger ship, the bastion at Singapore fell to Japan. Churchill refused to meet with Brooke-Popham upon his return, and the air-marshal maintained a lifelong, public, stoic silence. His sister committed suicide, which many blamed on the family’s public humiliation following the surrender of Singapore. Interestingly, Brooke-Popham’s name never appears in Churchill’s History of the Second World War, but Churchill himself does accept personal responsibility for the failure in Singapore.

Though Brooke-Popham was not a major actor in the broad sense, his life and times are well worth recounting, and Dye has written a well-researched biography. To Churchill, the air chief marshal was never a great commander and, in the end, a failure at his assigned task. Churchill seldom forgave failures.

Yet as Dye’s book makes clear, Brooke-Popham was far from solely responsible for the defeat at Singapore and the collapse of the British military power in the Far East. In fact, Brooke-Popham was very much a mirror of the calmer Victorian-Edwardian era, but the personality and military instincts that served him well earlier in his career were not assets in the Second World War, a time of radically changed geopolitics and cultural expectations. In addition, his command in the Far East suffered from an over-stretched British Empire and, eventfully, a war with three major military powers (Germany, Italy, and Japan). Dye paints a picture of a decent and well-meaning man, but one not up to the final assignment he was given.

The Naval Institute Press has published a handsome volume in its History of Military Aviation series, with excellent photography, maps, and an outstanding dust jacket. One weakness is the index, which misses some prominent names cited in the text. The bibliography is excellent, and the notes section informative. Clearly, the book makes a major contribution to recounting the life of a significant individual and understanding the challenges facing Great Britain in the Far East on the eve of the Second World War.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.