Finest Hour 184

The Constitutional King: George V

The future King George V opening the first Australian Parliament, 1901

July 24, 2019

Finest Hour 184, Second Quarter 2019

Page 16

By David Cannadine

The future King-Emperor George V, who would reign from 1910 to 1936, was born at Marlborough House, the palatial London residence of his parents, on 3 June 1865, and he would be christened Prince George Frederick Ernest Albert. He was the second son of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales and later King Edward VII, otherwise known as “Bertie,” and Princess Alexandra, daughter of King Christian IX of Denmark and always called “Alix.” His paternal grandmother was the bereaved but intimidating Queen Victoria. At the time of Prince George’s birth, the royal house of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was at the apex of the preeminent industrial, financial, imperial, and maritime nation in the world.

Sir David Cannadine is Dodge Professor of History at Princeton University and a trustee of the International Churchill Society. His many books include George V: The Unexpected King (2014) and In Churchill’s Shadow (2003), from both of which the text of this article is drawn.

There was a problem with the succession. Prince George’s older brother Prince Albert Victor Christian Edward (known as “Eddy”) was quiet, delicate, lethargic, apathetic, and a slow developer (he may, indeed, have suffered from what would now be termed attention deficit disorder). But despite Eddy’s shortcomings, it seemed inevitable he would one day inherit the throne, and this in turn meant that, as a younger son, Prince George lived the first twenty-six years of his life with no expectation of ever becoming king: like many monarchs whose reigns later turned out well, he was not born to succeed.

For schooling, the two young princes were entrusted to a young curate more interested in strict discipline and in ingratiating himself with royalty than in educating his charges. The non-results of this non-education were soon apparent. Prince George would always write in a slow, deliberate, childlike hand, and his spelling was permanently insecure.

2025 International Churchill Conference

A naval education was deemed to be the remedy. From 1883 to 1891 Prince George alternated between postings afloat and ashore. Like many sailors, he embraced a simple Christian faith: he would always be a middle-of-the-road Anglican, and from the time he went to sea, he read the Bible every day. He began to smoke heavily, and like his father before him, and his second son (George VI) after him, his health would suffer as a result. Also like his father, Prince George was obsessed by uniforms and decorations, protocol and etiquette, timing and punctuality; and, like many naval officers, he was impatient with nuance and complexity, and he mistrusted imagination and intuition. All his life, he would view the world from the vantage point (and often in the language) of the quarterdeck; in his early twenties, the smile vanished from his face, to be replaced by the bearded stare, by turns intimidating and defiant, baffled and uncomprehending, that scarcely changed thereafter.

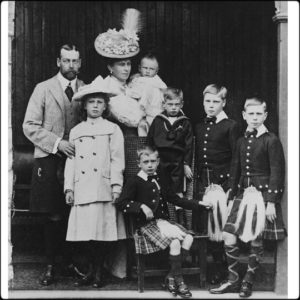

On 14 January 1892, Prince Eddy died after contracting influenza. It was neither the first nor the last time that a royal demise would prove to be a blessing, for in his mid-twenties the more stable and more reliable Prince George unexpectedly found himself in direct line of succession to the British imperial throne. He even found himself guided by his grandmother into proposing to his deceased brother’s fiancé Princess Victoria Mary of Teck. The wedding duly took place despite the couple scarcely knowing one another. Quite unlike his father, the Duke of York, as Prince George now became, would be an exceptionally loyal, devoted, and uxorious husband. Together the Yorks had six children: five boys and a girl—the eldest two both fated to succeed their father.

Following the death of Queen Victoria in 1901, George was created Prince of Wales by his father, the newly enthroned Edward VII. This title he held for nearly nine years until his father died on 6 May 1910. And so it was that King George V came to the throne during a tumultuous political crisis that involved, among many, the Liberal Home Secretary Winston Churchill.

Churchill

Winston Churchill had decided views about monarchy. One was that, despite the delinquencies of many individual monarchs, the English crown was a sacred, mystical, almost metaphysical institution, which connected the past, the present, and the future, and which proclaimed the unity and identity of the nation. A second was that, while other European nations preferred (or suffered) kings and queens who were generally despotic and absolute, the English evolved a more admirable form of “constitutional and limited monarchy.”

Churchill never forgot that while the mystical, unifying, moral, and imperial functions of the monarch were important, the whole thrust of English history had been to bring about a state of affairs where the king’s government was carried out by ministers, who were primarily answerable to Parliament, rather than to the Crown. He spelt out the ministerial doctrine early in his career. “The royal prerogative,” he insisted to his wife Clementine in 1909, “is always exercised on the advice of ministers, and ministers and not the crown are responsible, and criticism of all debatable acts of policy should be directed to ministers, not the crown.”

For all his veneration of the Throne as a national institution, Churchill was never overawed by members of the Royal Family, and he often gave the impression, especially in the early stages of his career, that he did not think much of particular monarchs. He had, after all, been born in a palace, which was more than George V or Edward VIII or George VI or Elizabeth II could claim.

King George V

While revering the British monarchy itself, therefore, Churchill often displayed a cavalier attitude towards the occupant. A varying degree of tension always existed between Churchill the young statesman and King Edward VII. The same held true at least during the early reign of George V, whom Churchill had first met socially at Cowes in 1887.

While he was Home Secretary, Churchill was scrupulous in giving his new sovereign full reports of public disorders in the Rhondda Valley in 1910 and Liverpool in 1911; he successfully oversaw the trial for criminal libel of Edward Mylius, who claimed George V had contracted a secret marriage in Malta in 1890, when serving with the Mediterranean fleet; and the King found the nightly reports of House of Commons proceedings, which Churchill sent him at Prime Minster Asquith’s request, “always instructive and interesting.”

In February 1911 Churchill substantially wrote the speech the King delivered at the unveiling of the Victoria Memorial, which ended with these rousing words: “No reign in this kingdom ever gathered up more carefully the treasure of the past, or prepared more hopefully the path of the future.” Later that year, on exchanging the Home Office for the Admiralty, Churchill wrote with flattering grandiloquence: “it has been a high honour to me to have stood so near to your majesty during the moving and memorable events of the first year of a happy and brilliantly inaugurated reign,” and he looked forward to receiving the King’s “aid and support,” based on “a lifetime of practical experience.” There were also visits to Balmoral. “The king,” Churchill told his wife in September 1913, “has been extremely cordial and intimate in his conversations, and I am glad to think that I reassured him a good deal about the general position.”

But while George V recognized Churchill’s zeal and energy, he was also influenced by his father’s disapproval, and generally thought him “irresponsible and unreliable,” a view which his own experiences tended to confirm. In 1908, he had told Churchill that he did not consider Asquith, who had just become Prime Minister, to be a gentleman. Of course, and as he later admitted, George should never have said such a thing, “but Winston repeated it to Asquith, which was a monstrous thing to do, and made great mischief.”

At Edward VII’s lying-in-state in Westminster Hall, Churchill had created a scene; and, during his first formal audience with the new monarch, he had tactlessly asserted that great change was necessary in the constitution, while expressing only perfunctory regret at the death of the late sovereign. There were also difficulties arising from the nightly reports of the Commons proceedings Churchill sent to the King, as when he observed that “there are idlers and wastrels at both ends of the social scale.” George V opined that such views were “very socialistic”; but Churchill stood by the offending phrase and objected to receiving “a formal notification of the king’s displeasure.” Peace was eventually restored; but the sovereign’s private secretary saw this as further evidence that Churchill was “a bull in a china shop,” while he continued to think the royal reproof unjust and a sign of the King’s lack of proper political impartiality.

Treacherous Waters

When Churchill moved to the Admiralty, matters did not improve. The new First Lord was a party politician and a zealous reformer; the King was a former naval person, head of the armed services, and a staunch believer in tradition and precedent. Churchill wanted to name a ship HMS Oliver Cromwell: not surprisingly, George V took violent exception to thus commemorating the regicide. Churchill then proposed HMS Pitt: but the King would not have that, either. In both cases, Churchill grudgingly gave way. “I have always endeavoured to profit from any guidance his majesty has been gracious and pleased to give me,” he wrote rather stiffly and unconvincingly after this second royal rebuff. Thereafter, their relations remained tense.

In January 1914, the King disapproved of Churchill’s threat to resign during the crisis over the Naval Estimates, and there were subsequent disagreements over promotions and honours. Churchill made no secret of his view that George V was a dim reactionary, and the King made it plain that Churchill was rude and inconsiderate. When the King objected to the First Lord’s proposal to withdraw battleships from the Mediterranean to safeguard British waters, in May 1912, Churchill exploded to his wife: “The king talked more stupidly about the navy than I have ever heard him before. Really it is disheartening to hear this cheap and silly drivel with which he lets himself be filled up.” Edward VII and George V disliked Churchill because they thought he was insufficiently respectful of their person and their prerogative; Churchill was unintimidated, and objected to what he regarded as inappropriate royal interference in matters which were wholly within the realm of Parliament.

But while for all his blustering radicalism Churchill still believed in a traditional Europe of traditional monarchies, the British crown and court were firmly against him by the time war broke out in 1914, and thereafter relations deteriorated still further. When Churchill urged that the British Navy would dig out the German Navy “like rats in a hole,” the King protested that such language was “hardly dignified for a Cabinet minister.” Soon after, Churchill rashly assumed command at Antwerp, which caused the King’s Private Secretary Lord Stamfordham to opine that the First Lord must be “quite off his head.” And when Churchill urged the reappointment of Lord Fisher as First Sea Lord, George V objected on the (not unreasonable) grounds that he was seventy-three and lacked the confidence of the Navy; but Churchill insisted, and the King had to give way.

All of this meant that Churchill’s downfall over the Dardanelles disaster in 1915 was greeted at Buckingham Palace with scarcely concealed relief. “It is,” Queen Alexandra informed her son, “all that stupid, young foolhardy Winston C’s fault which has upset everybody.” And the King agreed. Churchill had become “impossible,” a “real danger,” and he was “delighted” and “relieved” that he had been got rid of. So was his son, the Prince of Wales and future Edward VIII: “It is a great relief to know that Winston is leaving the Admiralty,” he wrote to his father. Thus ended the first phase of Churchill’s involvement with the British crown, which scarcely presaged the mutual admiration that would characterize their relations in the last two decades of his life.

A New View

During the inter-war years, Churchill’s attitudes towards monarchy, both in Britain and abroad, began to change, as the balance between criticism and approval, hostility and appreciation, shifted markedly in their favour. Like many pre-1914 Liberals, the First World War had left him saddened and uncertain, with his own reputation damaged and his career prospects diminished, and looking out on a social, political, and international landscape so brutally transformed and disturbed that it bore little resemblance to what seemed, in retrospect, to have been the Edwardian belle époque, with its settled values, historic institutions, venerable titles, and great estates. With the exception of Britain, all the great power monarchies—“mighty organisms built up by generations of patience and valour, and representing the traditional groupings of noble branches of the European family”—had gone.

The postwar changes, in continental circumstances and in Churchllian perceptions, help explain the substantial transformation in his relations with King George V. For he no longer regarded the British sovereign as the ignorant, blimpish reactionary of his radical Liberal days, but as the embodiment of decency, duty, and tradition, in a world all too often characterized by strife, anarchy, and revolution; and for his part, the King now warmed to Churchill both as an old friend and as a new conservative. The solution of the Irish problem seems to have had a great deal to do with this. Churchill greatly admired the “unswerving sense of devotion” George V displayed in visiting Belfast in June 1921, when he urged Irishmen to “forgive and forget” and the King applauded Churchill’s “skill, patience and tact” in seeing the Irish Treaty through the following year.

Thereafter, the King was “very sorry” about Churchill’s defeat at Dundee in 1922 and, while he was Chancellor of the Exchequer between 1924 and 1929, their relations were much more cordial than they had been before the First World War. When Churchill visited Balmoral in 1927, he “enjoyed” himself “very much” and had “a very good talk about all sorts of things.” And when holidaying at Deauville, Churchill observed the Shah of Persia at the gaming tables, dissolutely “parting with his subjects’ cash.” “Really,” he wrote to Clementine, “we are well out of it with our own gracious monarch.”

Resplendent Rebirth

But as always for Churchill, past history also taught contemporary lessons, as he pointed out in 1933 when he presented George V with the first volume of Marlborough: His Life and Times. “This is the story,” Churchill wrote, “of how a wise princess and queen gave her trust and friendship to an invincible commander, and thereby raised the power and fame of England to a height never before known, and never since lost.” “And,” he went on, “it is submitted in loyal duty to a sovereign under whom our country has come through perils even more grievous with no less honour.”

In the days of Marlborough, no less than in his own time, Churchill regarded the English monarchy as “the crowned embodiment of the nation.” But there was also the “broadening imperial theme,” begun when Queen Victoria “sought by every means in her power to bind her diverse people together in loyalty to the British crown,” and Churchill was eager to safeguard the King-Emperor as an imperial as well as a national sovereign.

Churchill developed these national, continental, and imperial themes more fully in his obituary notice of King George V in 1936, which he subsequently revised and reprinted in Great Contemporaries. In the course of the reign, massive changes had destabilized the world: empires and monarchies had fallen; dictatorships and anarchy had flourished; democracy had become incontinent and unfettered. Yet, “at the heart of the British Empire,” there was “one institution, among the most ancient and venerable which, so far from falling into desuetude or decay,” had “breasted the torrent of events, and even derived new vigour from the stresses.” “Unshaken by the earthquakes, unweakened by the dissolvent tides, though all be drifting,” the “royal and imperial monarchy stands firm.”

This was “an achievement so remarkable, a fact so… contrary to the whole tendency of the age,” that it could not be “separated from the personality of the good, wise and truly noble king whose work is ended.” He was “uplifted above the class-strife and party-faction;” he never feared British democracy; he reconciled labour and socialism to the constitution and crown; he “revivified the national spirit, popularized hereditary kingship;” and in so doing, won the affection of his subjects and the admiration of mankind. “In a world of ruin and chaos,” Churchill concluded, “King George V brought about the resplendent rebirth of the great office which fell to his lot.”

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.