Finest Hour 183

Sarah Churchill: Winston’s Right-Hand “Man”

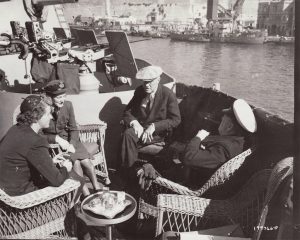

Sarah joins her father on deck

April 12, 2019

Finest Hour 183, First Quarter 2019

Page 22

By Catherine Grace Katz

Catherine Grace Katz’s book The Daughters of Yalta will be published in 2020. Extracts from the writings of Sarah Churchill are reproduced with the permission of the Master and Fellows of Churchill College, Cambridge.

One day in early November of 1943 I was summoned to the commanding officer and told by him that leave of absence was to be granted to me so that I could accompany my father on an important journey. The RAF station at Medmenham was quite near to Chequers.…I hurried there now, and my father told me that a conference between the President of the United States, Stalin and himself had been arranged at Tehran, that the President, despite his health and physical handicap was making the long journey and that Stalin had finally been lured from his lair. My father and the President were to meet in Cairo before the conference in Tehran. I was to accompany my father as one of his aides-de-camp….I walked on air.—Sarah Churchill1

Though many people remember Mary as the most visible of Winston Churchill’s children from the Potsdam Conference in 1945 through the postwar period, few realize that it was actually her older sister Sarah who accompanied the Prime Minister as his aide-de-camp during his tripartite wartime conferences with Franklin Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin. Early in the war, Winston and Clementine had decided that a member of the family should accompany the Prime Minister on his travels as his confidante and supporter, as well as a chronicler of family history.

An actress by trade, Sarah Churchill had joined the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force—the WAAFs—as an interpreter of aerial reconnaissance photographs in autumn of 1941. At twenty-nine, she was the perfect person to accompany her father. As a WAAF Section Officer, she was familiar with the inner workings of military and political hierarchy and bureaucracy. As an actress, she was well prepared to handle the performance aspects of international diplomacy. Most importantly, having spent the last two years immersed in the minutest details of the war in the Mediterranean and North Africa, she was well aware of the crucial issues at stake at these conferences, namely, the opening of the western European front.

When the commanding officer’s summons came, Sarah was at RAF Medmenham poring over images of enemy ships, troops movements, and supply lines in the Mediterranean and North Africa taken by reconnaissance pilots from 10,000 feet in the sky. Clementine and twenty-year-old Mary had both joined Winston at the First Quebec Conference in August 1943, but this time, the Prime Minister requested that Sarah accompany him for his upcoming conferences with Roosevelt and Chiang Kai-shek at Cairo and Roosevelt and Stalin at Tehran in late November and early December.

On 12 November 1943, Sarah and her father departed from Plymouth aboard HMS Renown. They sailed to Alexandria via the Strait of Gibraltar and then flew on to Cairo to meet Roosevelt and Chiang on 22 November about the state of the Pacific War.

Road to Teheran

My duties were mainly to see, along with others, to my father’s comfort and wishes, to relay messages, and to drape myself silently along with the coat racks in the antechambers of the conference rooms with other ADCs assigned to similar duties. I did not have any “ideas above my station.”2

Though Sarah was the Prime Minister’s daughter and the only female delegate at Cairo aside from Madame Chiang, she tried not to call attention to herself and behaved like any other British officer on duty.3 As soon as she arrived in Egypt, Sarah and the other ADCs who had accompanied their respective diplomats, generals, and admirals on the trip were summoned by a monosyllabic officer and briefed on the logistical arrangements, including how to use the telephones and work the lavatories. It was hardly glamorous work for a woman who had recently been a starlet on the stage and had made her first appearance on screen, but Sarah found the atmosphere thrilling. The diplomatic intrigue and plainclothes detectives around every corner and under every window infused each whispered conversation with dramatic flair, and the palatial buildings and luxurious surroundings in Cairo were more impressive than any film set Sarah had ever seen. While her father met with Chiang, Sarah and the Chinese ADCs hovered in the antechamber until their respective principals summoned them. Some of the Chinese aides spoke English, so they passed the time making spirited conversation.4

Along with her father’s doctor Lord Moran, Sarah and the Prime Minister’s naval aide Commander Charles “Tommy” Thompson also tried to look after Churchill’s health. The Prime Minister had caught a cold en route to the meeting, and—though he took the medicines Lord Moran prescribed—ensuring he had proper rest was often no easy task, since he liked to work until the wee hours of the morning. By the time they left Cairo for Tehran on 28 No- vember, Churchill’s cold had turned into laryngitis and the early stages of pneumonia. Upon reaching Tehran and learning that Stalin had already arrived, the Prime Minister wanted to meet with his Soviet counterpart right away. Sarah, however, recognized that her father was exhausted after travelling while ill. Under such circumstances, an immediate meeting with Stalin would have placed Churchill at a disadvantage. After much intense debate, Sarah and Lord Moran finally convinced their charge to rest and meet Stalin the next day as planned. The following morning, Churchill’s spirits were up and his voice had returned. making for a more advantageous beginning to the conference.5

High Table

But now to the dinner: almost one of the first toasts that was drunk was mine! This was proposed by the President. It was terribly sweetly done. I was particularly touched because he couldn’t see me—but he has twice remembered me when I wasn’t around—which I think is wonderful. Stalin got up and came round and touched glasses with me; and I went to the President and thanked him, and he said: “I’d come to you my dear but I can’t.” I love him.6

Though Sarah downplayed her role as her father’s aide with humility and humor, describing herself as just another junior officer in the delegation, there were several occasions throughout the conference when her identity as the Prime Minister’s daughter usurped that of Section Officer and ADC. In her mother’s absence, Sarah stood in as her father’s partner for the ceremonial aspects of the conference, particularly at the dinner on 30 November, which became a party in honor of Winston’s sixty-ninth birthday. After a long day of intense discussions about Operation Overlord, the impending invasion of France slated to commence in the late spring of 1944, the mood turned celebratory. Sarah sat at the table as an equal alongside the foremost individuals in the alliance: Roosevelt, Stalin, Alan Brooke, “Pug” Ismay, George Marshall, Harry Hopkins, Averell Harriman, John Gilbert Winant, and Vyacheslav Molotov. In many ways, it was a role for which Sarah had been trained since childhood. When her father’s friends and colleagues across government, the military, and the arts would come to dine at Chartwell, Sarah and her siblings would join in the meal (and, in her brother Randolph’s case, in the discussion), much to the illustrious guests’ surprise and occasional chagrin.

Over the course of the war, Sarah came to know Roosevelt and Stalin as few outside the upper echelons of military and government ever did. Sarah developed genuine affection for Roosevelt, whose paralysis seemed to disappear from one’s notice almost immediately, but her feelings towards Stalin were more complicated. Though small in stature, he could be “a frightening figure with… bear eyes,” in which light seemed to dance “like cold sunshine on dark waters.” He had a readily apparent and sharp wit and would occasionally crack pointed jokes at the dinner table, but behind his eyes lurked an intensity that never truly disappeared.7

Principal Support

On the way home that night my father…fell silent and presently said, “War is a game played with a smiling face, but do you think there is laughter in my heart? We travel in style and round us there is great luxury and seeming security, but I never forget the man at the front, the bitter struggles, and the fact that men are dying in the air, on the land, and at sea.”8

In Sarah’s own humorous description of her role and responsibilities, she sells short the greatest value she brought to her father at Cairo and Tehran, and again when she accompanied him to Yalta just over a year later. As Lord Moran wrote in his published diary of the war years, Churchill, unlike Roosevelt, never had a Harry Hopkins—an adviser who served as the Prime Minister’s closest confidante and supporter on all matters throughout the duration of his tenure at Downing Street.9

Churchill did have several trusted colleagues who collectively formed something similar to a Hopkins presence in his life: Anthony Eden, Lord Beaverbrook, Brendan Bracken, Lord Cherwell. But none could offer him total and all-encompassing support. For Churchill, his family filled this gap. In moments of doubt, insecurity, fear, and anxiety, he would pour out his worries to his wife Clementine, or, in her absence, his daughters Sarah and Mary. They were the first to assuage his concerns and celebrate his victories. For within the political arena, especially at the highest levels of international diplomacy, there was no one other than his family whom Churchill could trust to share his true feelings about his Allied counterparts and the fateful decisions they made together.

On numerous occasions throughout the Tehran and Yalta conferences, the Prime Minister bared his soul to Sarah, sharing with her the things he could never say at the conference table. Though at times Churchill seemed to carry the weight of the world, Sarah was there to share that burden with him through two of the most complex negotiations of the Second World War, where duplicity and gamesmanship abounded amongst men whom circumstance had thrown together as comrades if not friends.

Darling Papa

I have been meaning to write and tell you something of what the journey to Cairo & Tehran meant to me, and how being with you so closely…has enriched my life so immeasurably.…Darling darling Papa, so long as I live I’ll never forget our wonderful journey—over the years the pageantry and colour of those great events may dim or get confused—but I will never forget.…All this, and more, I have with me forever. I love you very dearly.10

Roosevelt had a complicated relationship with his children, including his daughter Anna, whom he allowed to attend the Yalta Conference as his ADC only after observing the value Sarah Churchill had brought to her father as his aide. Speaking about her father, whom she adored at a distance, Anna once remarked to a friend, “He doesn’t know any man and no man knows him. Even his own family doesn’t know anything about him.”11 By contrast, Sarah Churchill knew her father’s mind better than anyone, save for her mother.

For Sarah, joining the delegations at Tehran and Yalta was more than just a chance to work alongside the Prime Minister as a valued colleague. It was also deeply personal, since the journeys represented two of the scarce opportunities Sarah and Winston found to spend a material amount of time together as father and daughter during Sarah’s early adulthood and the war.

Sarah’s career and marriage to fellow actor Vic Oliver in 1936 had kept her far from home, because the couple traveled in touring productions across Britain and the United States. Sarah and Vic had separated by the time war broke out, but the WAAFs soon replaced the theater, keeping Sarah at RAF Medmenham and away from her family for long stretches of time. Serving as Winston’s ADC at the tripartite wartime conferences allowed Sarah to recapture the closeness she had once felt with her father as a little girl after distance had crept between them during her marriage, her pre-war career as an actress, and the early days of the war. To the world, Winston Churchill was the Prime Minister, the man who had saved Britain as she stood alone against the Nazi scourge in 1940, but to Sarah he was still her beloved Papa.

Endnotes

1. Sarah Churchill, A Thread in the Tapestry (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1967), p. 57.

2. Ibid., p. 59.

3. Several female typists were included in the party that travelled to Cairo and Tehran, but their duties were strictly limited to clerical work.

4. Sarah Churchill to Clementine Churchill, 23 November 1943, Churchill Archive Centre, SCHL 1/1/7.

5. Sarah Churchill to Clementine Churchill, 4 December 1943, SCHL 1/1/7.

6. Sarah Churchill, Keep on Dancing (New York: Coward, McCann and Geoghegan, 1981), p. 122.

7. Churchill, A Thread in the Tapestry, p. 65.

8. Ibid., p. 63.

9. Lord Moran, Churchill at War 1940–45 (New York: Carroll and Graf, 2002), p. 198.

10. Sarah Churchill to Winston Churchill, 28 March 1944, CHAR 1/381/59–61.

11. Robert Ferrell, The Dying President: Franklin D. Roosevelt 1944–1945 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1998), p. 143.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.