Finest Hour 183

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – Painting with a Purpose

May 6, 2019

Finest Hour 183, First Quarter 2019

Page 44

Review by David Freeman

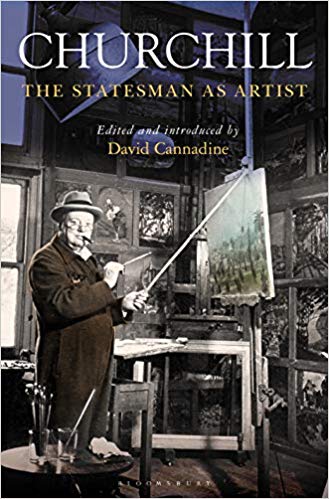

David Cannadine, ed., Churchill: The Statesman as Artist, Bloomsbury, 2018, 172 pages, £25/$30. ISBN 978–1472945211

Writing in his famous essay Painting as a Pastime, Winston Churchill said of his favorite hobby: “I know of nothing which, without exhausting the body, more entirely absorbs the mind.”

There have been several good books that gather together examples of Churchill’s paintings. This is the first book, however, that gathers together all of Churchill’s speeches and writings about painting. It is worth reading.

Sir David Cannadine writes and speaks frequently about Churchill. As a professional historian, his resume is unsurpassed. So it is notable that he does not underestimate the importance of painting in Churchill’s life. He has never been alone. Included in this book are essays by six people from the professional art world during Churchill’s time showing their appreciation for the statesman’s passion.

In his introduction, Cannadine observes that “Churchill spent most of his waking hours talking incessantly…painting was the only activity he seems to have carried out in concentrated peace and complete silence. It absorbed him for many continuous hours, taking his mind off everything else, and off everybody else, too—which was why he found it so therapeutic.”

Painting as a Pastime, which originated as two separate essays published before the war and then printed together in a single volume in 1948, obviously lies at the heart of this collection. The many observations therein represent Churchill’s most heartfelt thoughts on the subject, and Cannadine includes a 1950 review of the book by Eric Newton.

Readers may be surprised to learn, though, that Churchill was often invited to speak to the Royal Academy long before the Second World War. In fact, he even twice spoke to the Academy’s annual banquet at Burlington House before the First World War—before he himself had started painting. On those occasions in 1912 and 1913, however, Churchill, speaking as First Lord of the Admiralty, confined himself to brief remarks about naval matters.

Even after the Great War, when he had taken up painting as a consolation in the aftermath of the Dardanelles campaign, Churchill’s speeches to the Royal Academy initially avoided any observations about art and artists. Speaking in 1932, Churchill delivered a heavily sarcastic address comparing the Royal Academy to the “National Academy” of politics. He said of Labour leader Ramsay MacDonald, who had recently formed a National Government based on an enormous Conservative majority: “For a long time…I thought there was a good deal too much vermillion in his pictures.” Churchill then goes on to praise MacDonald for changing his style and adding to his palette so many shades of “British [read Tory] true blue.”

In the next three speeches that Churchill made to the Royal Academy before the war, he finally began to venture opinions on the canvasses displayed during the annual exhibition. Even this, however, is done with tongue firmly in cheek. “There is a strange absence of the apples, loaves, guitars and dishcloths which pervade the general run of galleries,” he dryly observed in 1932.

Churchill never pretended to be anything other than an amateur painter and did not want the art world to view him as an interloping poseur. He loved and championed painting for the relaxation that it provided him. But he also took lessons with some of the leading artists of his day and enjoyed having serious and probing discussions with them. They in turn respected his enthusiasm and his efforts, which—at their best—were very good indeed.

With some reluctance, but encouraged and guided by authorities such as Sir Kenneth Clark, Churchill allowed a few of his best paintings to be displayed at the Royal Academy. He continued to attend the annual banquet when it was revived after the Second World War, although one year he found himself embarrassed when the president, Sir Alfred Munnings, went on a drunken tirade denouncing modern art in all it forms in remarks carried live on the BBC while claiming that Churchill was in full agreement— which he was not. Munnings had to resign.

Churchill delivered his most important thoughts about art in a speech to the Royal Academy in 1953, when he said: “The function of such an institution as the Royal Academy is to hold a middle course between tradition and innovation. Without tradition art is a flock of sheep without a shepherd. Without innovation it is a corpse.” For Churchill, art was always a living enterprise, and we can share his enthusiasm through this wonderful collection.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.