Finest Hour 183

Making Woolton Pie: Rebuilding the Conservative Party’s Campaign Machine

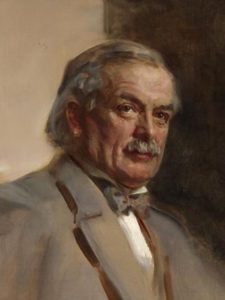

Churchill’s peacetime cabinet (Woolton is front row, second from left)

May 29, 2019

Finest Hour 183, First Quarter 2019

Page 26

By Iain Carter

Iain Carter is Political Director of the Conservative Party. He has previously been a special adviser to the Leader of the House of Lords and a member of the Conservative Research Department.

When it came to preparing meals during the Second World War, the British people had to make do with what they were allocated under the ration. Francis Latry, Maitre Chef de Cuisine at the Savoy Hotel, came to the rescue with a recipe for vegetable pie that was then popularized by Lord Woolton, the Minister of Food responsible for overseeing the rationing system. “Woolton Pie,” as the pastry became known, would be forgotten as soon as the end of wartime austerity could be achieved. Making the most of sparse beginnings, however, was something the former Cabinet minister would be called upon to repeat.

In a private conversation following Labour’s landslide victory in the 1945 general election, Winston Churchill remarked, “I shall not be idle. I shall write, I shall speak on the wireless and I shall still be an MP, although I shall never return to Number Ten.”1 The Conservatives had suffered their worst defeat in two generations, yet less than six years later Churchill would return to Number 10 to begin his second premiership at the head of a majority government. He was propelled there in part because of a rejuvenated Conservative Party campaign machine, in addition to the changes in policy and policy making which are more commonly focused on.

Churchill’s leadership of the 1945 campaign, on balance, is likely to have prevented an even poorer performance, notwithstanding his disastrous “Gestapo” speech. Yet the Party’s problems were undoubtedly compounded by the weakness of its campaigning infrastructure, both locally and nationally. Despite the suspension of normal politics as a result of the formation of the wartime coalition, both major parties made attempts to maintain their capacity to campaign. A message sent out to local constituency associations from Churchill urged action in this regard, saying: “it is vitally important that, side by side with our war effort, ways and means should be found of keeping the Conservative Party organisation in being and ready to be tuned up when the time comes.”2

Yet these efforts were to prove insufficient. When reporting on the state of the party’s organisation to Churchill in 1945, area agents were unanimous in the view that an election could not be won in the summer because of the poor state of the Party. This view was also shared by the then Party Chairman Ralph Assheton. A sign of just how poor this was is provided by the fact that party professionals judged that even pushing back the election to the autumn would not have a material efffect on the result, notwithstanding the improvements that could be made in the intervening months.3

Enter Woolton

Efforts to rebuild the Conservative Party machine began immediately after the general election, when the dire predictions were realised. In the first year following the defeat, a number of important structural changes were made under Assheton—who initially stayed on as Party Chairman. There was also a renewed focus on research and political education.4 The Conservative Research Department was re-established and went on to take a more central role than it had played before 1939.5 The creation of the Conservative Political Centre gave members the training they needed to make the Conservative case from first principles. All this proved valuable, but the crucial developments were to come under Assheton’s successor.

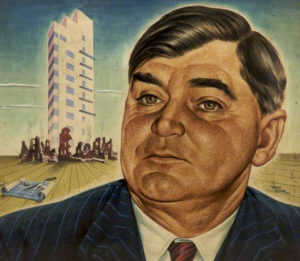

Frederick Marquis, as Lord Woolton was originally known, built a successful career before the war as an executive of Lewis’s department store chain and had been rewarded with first a knighthood and then a peerage. Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain brought the politically non-partisan businessman into the Government as Minister of Food in April 1940, a position he retained when Churchill succeeded Chamberlain as Prime Minister the following month. In 1943, Churchill appointed Woolton to be Minister of Reconstruction with the difficult assignment of planning for the post-war period when Britain would be left with meagre resources.

Woolton had not been a member of the Conservative Party during the war but was prompted to join by the election defeat in 1945. In a message to Churchill he wrote: “I am ashamed at the way this country has treated you and would be honoured to serve with your whip.”6 And thus it was that Woolton came to be appointed Party Chairman in 1946. Once again, he would succeed in making success out of scratch ingredients. The most notable changes that followed under his leadership were in three areas: members, money, and manpower.

Swelling the Ranks

Notes for Churchill’s 1946 party conference speech include a section on the need to rebuild the Party, with a focus on membership and money. He was to say: “To extend our influence we must constantly broaden the base of our membership. We must also broaden our financial resources and derive our Party funds from millions of small subscribers.” Although this whole section appears to have been dropped, having been crossed through on the manuscript and missing from the later published collection of post-war speech, it nevertheless gives an insight into his priorities.7 And in these two areas Woolton delivered significant improvements.

A major, on-the-ground membership recruitment campaign began soon after Woolton’s appointment. It was based on the simple principle that a small group of homes made up a “block” that would be the responsibility of one volunteer. Three hundred constituencies were involved, and they successfully added 226,000 new members by the winter of the following year. Despite this, it was thought that more could be done, and Woolton launched an even more ambitious plan for 1948. This time he aimed to get a million new members in just two months. 429 constituency associations took part, and the efforts of volunteers and staff across the country helped to beat his goal with 1,049,000 members added by 30 June 1948. Party membership then stood at more than 2.2 million and continued to increase slowly afterwards, although no future campaigns were able to match the phenomenal efforts between 1946 and 1948.8

Raising the Cash

Like Churchill, Woolton recognised that, as well as more members, the Party needed to raise and spend significantly more money if it were to compete with Labour. With the confidence gained through a career in business, Woolton pushed ahead with improvements, but this left the Party spending five times its resources, by his own admission.9 The Party Chairman initially pushed associations to raise more locally and in 1947 requested they set a fundraising target of between £2,000 and £3,000 a year (between £74,000 and £111,000 in today’s prices.)10 These were sums that few associations at the time were likely to have been meeting, nor would they have found them easy to raise even with the provision of more guidance from the centre. In addition, the removal of the practice of MPs and candidates making very large local contributions, as a result of the implementation of the Maxwell Fyfe Reports in order to increase the diversity of representatives, put constituency associations under further financial strain. Nevertheless, the reforms—out of necessity—simultaneously forced associations to improve their fundraising capacity. The same reports also established a quota system for local associations to contribute to the activities of Conservative Central Office (CCO) via a Central Fund.11

Alongside improving local fundraising, Woolton also pushed forward with a national fundraising campaign. Despite the risks that another failure might prove “fatal,” he rejected advice to seek a more modest £250,000 and instead set a target £1 million, saying it “gave the party the thrill of high endeavour.”12 The ambition of “Lord Woolton’s Fighting Fund” cannot be underestimated, sitting at £37 million in today’s prices.13 Yet it proved a success, and the target was met. In Woolton’s eyes this achievement went beyond just finance. It represented the beginning of the Party’s fight back.

He recalled in his memoirs: “That appeal was the beginning of a long trail of hard individual work done by the rank and file of the Party, who not only gave their time to go canvassing, but trained themselves to do it well. The party members throughout the country began to realise that it was not the large public meetings addressed by important people that would be the predominant factor in winning the election, but the advocacy of people who, combining personal friendliness in their approach to individuals with a sense of high national purpose and deep political conviction based on knowledge, took these things to the houses of the voters. “Operation Knocker” as I called it.”14

Developing the Manpower

Credit: Chartwell Booksellers

How Woolton put the results of these fundraising successes into action was the third significant way in which he turned around the Party’s campaign machine. The professional party was expanded, with new staff recruited to Conservative Central Office, allowing it to support better the volunteers who were the leading edge of the Party’s campaign efforts. As Woolton acknowledged: “The most difficult task that we set ourselves to perform at the Central Office was to translate these political arguments into simple forms that were likely to be useful and convincing in ‘Operation Knocker.’”15 Locally, more agents were recruited and trained. During the war, some areas had seen more than half of their qualified agents leave.16 Yet as a result of this recruitment drive the number of fully qualified agents doubled. By the 1950 election, 527 out of the 542 constituencies in England and Wales had a full-time party professional to support them.17 The majority of these continued in post for the 1951 election. They were also better trained than ever, making possible “the creation of a national force of full-time political workers who, though locally employed, were centrally trained and had a highly developed awareness of serving in a national organisation.”18

Efforts were also made to improve the efficacy of the Party’s volunteers. The approach that had helped in the recruitment of members and increasing subscriptions was used in campaigning, with the organisation taking inspiration from the structure of wartime air raid defence. In the best-covered area, there were volunteers at the block, group, polling district, ward, and constituency level.19 The party’s youth wing also saw rapid development and in Woolton’s own words “became probably the most powerful political youth organisation in the free countries of the world,” providing many of the party’s best campaigners, as well as a new generation of politicians.20

A New Spirit

Woolton may not have been Churchill’s first choice for Party Chairman. He had told Anthony Eden that he favoured future Prime Minister Harold Macmillan for the role as “one of our brightest rising lights.”21 As has been shown, however, Woolton proved to be an inspired choice. The service he went on to provide Churchill and the Conservative Party was considerable indeed. Paying tribute to Woolton following his death, Lord Carrington told the House of Lords: “It was to his experience of business and organisation, to his leadership, and to his strong personal example that we owed the great revival which took place in the six years after that election.”22

Following defeat, Churchill spoke of his distress at the prospect of “sinking from a national to a party leader.”23 Yet—in part because of the rebuilt Conservative Party machine—this fear was not realised, and he was able to seize his last chance for a successful return to office in 1951. That victory laid the foundations for the thirteen years of Conservative government that followed. As Woolton said: “I never had any doubt that, although the majority would be small, we were going to win that election in 1951, for we had generated a new spirit not only in the Tory Party, but in the country.”

Endnotes

1. Andrew Roberts, Churchill: Walking with Destiny (London: Allen Lane, 2018), pp. 885–86.

2. J. D. Hoffman, The Conservative Party in Opposition 1945–51 (London: Cox and Wyman, 1964), p. 57.

3. Ibid., p. 22.

4. Ibid.

5. Lord Butler, ed., The Conservatives: A History from Their Origins to 1965 (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1977), p. 421.

6. “Lord Woolton, 81, Food Minister in Early Years of War, Is Dead; Rebuilt British Conservatives in 9 Years as Chairman— Initiated Ration Points,” New York Times, 15 December 1964, p. 3.

7. Churchill Archives Centre, “Every Dog His Day,” 5 October 1946, CHUR 5/9/136-199; Winston S. Churchill, “Conservative Party Conference at Blackpool: A Speech on 5 October 1946,” in The Sinews of Peace, ed. by Randolph S. Churchill (London: Rosetta Books, 2014).

8. Hoffman, pp. 84–90.

9. Conservative Party, Conference Report, 1948, p. 77.

10. Conservative Party, Conference Report, 1947, p. 20; Bank of England, “Inflation calculator” < https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator> [accessed 2 January 2019].

11. Hoffman, pp. 97–100.

12. Lord Woolton, The Memoirs of the Rt. Hon. the Earl of Woolton (London: Cassell, 1959), p. 336.

13. Bank of England, “Inflation calculator.”

14. Woolton, p. 337.

15. Ibid., p. 343.

16. Andrew Thorpe, “Conservative Party Agents in Second World War Britain,” Twentieth Century British History, vol. 18, no. 3 (2007), pp. 334–64.

17. H. G. Nicholas, The British General Election of 1950 (London: Macmillan, 1951), p. 24.

18. Ibid., p. 25.

19. Hoffman, p. 84.

20. Woolton, p. 338.

21. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, vol. VIII, Never Despair 1945–1965 (London: Minerva, 1988), p. 227, n. 1.

22 HL Deb, 15 December 1964, vol. 262, col. 354.

23. Winston S. Churchill, Triumph and Tragedy (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1986), p. 512.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.