Finest Hour 183

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – Dynamic Duo

April 17, 2019

Finest Hour 183, First Quarter 2019

Page 48

Review by Kevin Ruane

Kevin Ruane is author of Churchill and the Bomb (2016) and teaches history at Canterbury Christ Church Univeristy.

David Cohen, Churchill and Attlee: the Unlikely Allies Who Won the War, Biteback Publishing, 2018, 356 pages, £22. ISBN: 978–1785903175

As a cursory internet search will confirm, the popular perception of the Winston Churchill-Clement Attlee relationship is largely shaped by two purportedly Churchillian remarks. The first—the wording alters marginally depending on where one looks— goes thus: “An empty taxi drew up outside Number 10 Downing Street and out stepped Mr Attlee.” The second has Churchill dismissing Attlee “as a sheep in sheep’s clothing.” From these quotes, it is reasonable to infer that Churchill regarded Attlee, the Labour Party leader (1935–55) and his deputy as Prime Minister during the Second World War, as a vacuous non-entity. There is, though, a problem with such an inference: Churchill did not actually utter the remarks upon which it rests. Indeed, when apprised of the barbs he was supposed to have shot in Attlee’s direction, Churchill became angry and upset.

Popular perceptions are quick to set but slow to shift. In 2002, the BBC commissioned a public television poll to determine the “Greatest Britons” of all time. Churchill came top. Attlee did not even make the top 100. In contrast, David Cohen reminds us in his new book Churchill and Attlee that in 2004 British historians were polled on the most successful UK Prime Minister of the twentieth century. Attlee came first, Churchill second. Historians, then, as opposed to the public, have never lost sight of Attlee and his importance.

David Cohen is not a professional historian; he is a psychologist, documentary filmmaker, and author of a best-selling book on the late Princess Diana. As such, Churchill and Attlee, his treatment of the forty-year Churchill-Attlee relationship, is a work of popular, not academic history. By building, however, on John Bew’s positive 2016 assessment of Attlee, Citizen Clem, and through his own potential to reach a wider readership-demographic, Cohen’s study may further the “rediscovery” of Attlee.

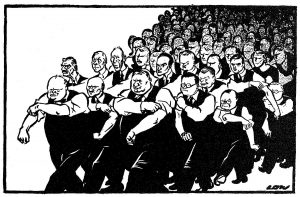

For many browsers, Churchill will be the initial draw (his name retains magnetic allure on dust-jackets), but Cohen’s readers, once engaged, will find themselves learning a good deal about Attlee. Quiet, reserved, and modest, Attlee offers a stark contrast in personality-type to Churchill’s “primordial thrust” (as his son Randolph once put it). Nonetheless, as Cohen shows, Attlee was one of the great political doers and achievers in British history.

Born in 1883 (making him Churchill’s junior by nearly a decade), Attlee was a middle-class, Oxford-educated politician whose “living faith” was socialism. He served with bravery in the Great War (by a quixotic twist of shared history, he fought in the Gallipoli campaign in 1915, which produced one of Churchill’s most searing political and personal set-backs). After the war, Attlee was active in local politics before entering parliament in 1922 as a Labour MP committed to addressing social and economic inequality. In 1935, he assumed the Labour leadership. Five years later, in May 1940, in agreeing to support a Churchill-led national government, Attlee played a critical role in ensuring a Churchill rather than a Halifax succession to Chamberlain. Thereafter, he served as Churchill’s loyal deputy in the wartime coalition before going on, as Prime Minister himself from 1945 to 1951, to establish the welfare state, with the National Health Service as the jewel in its crown.

In Churchill and Attlee, Cohen not only challenges the myth that Churchill was serially contemptuous of Attlee but demonstrates how, as wartime Deputy Prime Minister, Attlee led on the Home Front so effectively that Churchill was left free to focus his attention on military strategy or absent himself from the country on overseas diplomacy. Cohen writes with pace and style on the overlaps, interactions, and occasional interdependency in the Churchill-Attlee relationship. In terms of sources, he relies heavily on the obvious published material but has also consulted the Attlee papers at the Bodleian Library in Oxford and mined the riches of the Churchill Archives Centre in Cambridge. Academic historians looking for footnotes or other explicit evidence of Cohen’s research will look in vain; there are none. Instead, as popular history is wont to do, his narrative bowls along in a fluent synthesis of his research findings.

Readers of Finest Hour will discover little new about Churchill from this book but may be surprised at the extent of the principles and attitudes that Churchill and Attlee held in common—a keen patriotism, devotion to monarchy, a domestic social reformist outlook (albeit of very differing ethos), and a love of the English language, literature, and poetry. At the same time, their political-ideological differences cannot be airbrushed out of existence.

After the war, when Attlee was Prime Minister, the House of Commons became the forum for many a Churchill-Attlee duel. The sparring continued following Churchill’s return to Number 10 in October 1951. In making the case for unalloyed mutual respect behind par-for-the-course political jousting, Cohen is perhaps too quick to dismiss Churchill’s “Gestapo” jibe during the 1945 General Election campaign—the implication of nascent Nazi-style Labour totalitarianism was personally wounding to Attlee. Similarly, in his chapter on Churchill’s 1951–55 peacetime government, Cohen ignores how Churchill waged an unpleasant vendetta against Attlee for his alleged surrender of the UK’s right (which Churchill felt he had established with Roosevelt in the war) to be treated as a full US partner in nuclear weapons development. This issue eventually led to one of the most humiliating parliamentary experiences of Churchill’s career in the hydrogen bomb debate of April 1954. But beyond these and a few other exceptions, Cohen is right: the things that united Churchill and Attlee were greater than those that divided them.

Attlee will continue to rank second to Churchill in the popular estimate, no matter how much historians like Bew and writers like Cohen assert his significance. But if that is to be Attlee’s fate, what a number two he was! Attlee was a political giant whose integrity, devotion to public service, and dedication to the national interest towers above most, if not all, British leaders of more recent vintage. Notwithstanding their spats, Churchill admired him. The feeling was mutual. “We have lost the greatest Englishman of our time—I think the greatest citizen of the world of our time,” Attlee intoned upon Churchill’s death in 1965. When, two years later, Attlee himself passed away, another great Englishman was lost.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.