Finest Hour 181

The British Army in Normandy: Winning the War the Wrong Way

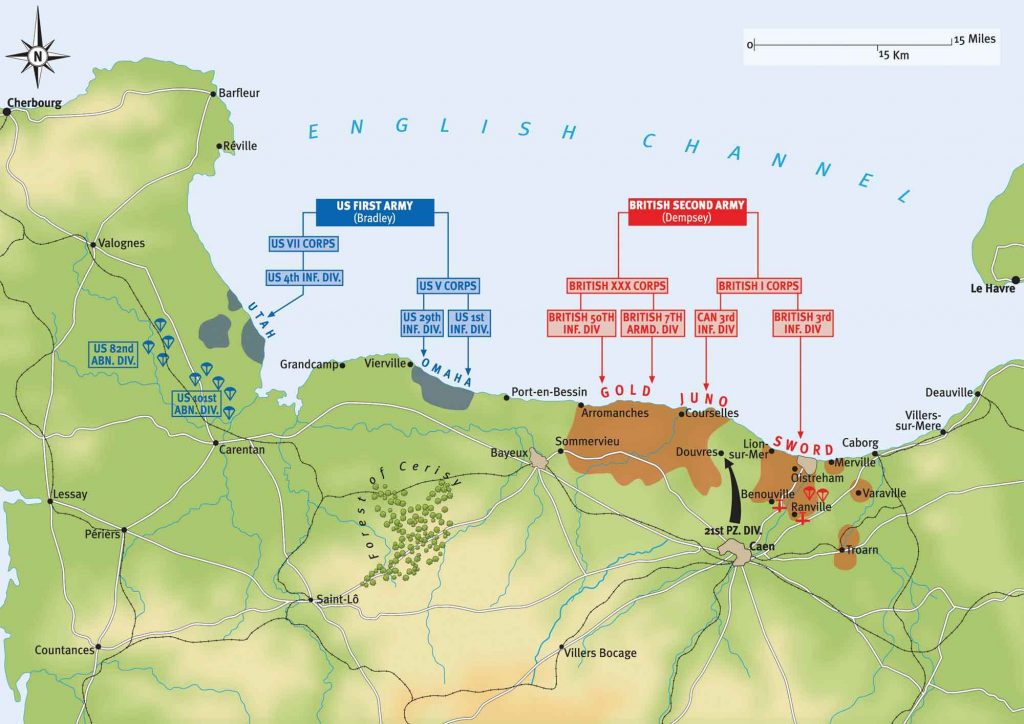

Map of landing zones on D-Day, 6 June 1944

December 12, 2018

Finest Hour 181, Summer 2018

Page 26

By Edward E. Gordon and David Ramsay

Edward E. Gordon and David Ramsay are co-authors of Divided on D-Day: How Conflicts and Rivalries Jeopardized the Allied Victory at Normandy (Prometheus Books, 2017).

The commander sighed. “Well, there it is: it won’t work but you must bloody well make it.”1 With these words Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, chief of the Imperial General Staff, instructed Lieutenant General Sir Frederick E. Morgan in 1943 to begin preparing a cross-channel invasion plan. From the first day of the war, America’s leaders were determined to confront and defeat the German army speedily by invading northwestern Europe. But because the British had recently been decisively defeated by German forces at Dunkirk as well as in Norway and Greece, Churchill and the British armed forces chiefs of staff were much more cautious. They still remembered the slaughter of an entire generation on the Western Front during the First World War.

Britain’s war leaders also harbored grave doubts about the battle readiness of US soldiers, believed that American generals lacked combat experience, and were skeptical about America’s ability to increase the production of war materials rapidly.

From December 1941 to June 1944 this British foreboding cast a pall over the very idea of mounting a successful cross-channel invasion. “Why are we trying to do this?” Prime Minister Winston Churchill was shouting even as late as February 1944. Almost up to the day of the actual Normandy landings, Churchill continually bombarded the Americans and his own generals with alternatives such as invading Norway, Portugal, or the Balkans. This continued insistence on these diversionary maneuvers weakened his relationships with the American commanders.

Operation RANKIN was the British chiefs of staff alternative plan to implement this peripheral strategy with attacks in the Mediterranean Region, the Balkans, Norway and elsewhere. These thrusts would help to wear down the Nazi empire in Europe until it collapsed. Perhaps it was all wishful thinking on their part, but as late as November 1943 the British Chiefs still considered the possibility of implementing RANKIN as an alternative to a major landing in Normandy.

Here two fundamentally opposing conceptions of war—the indirect versus direct approach—collided. For the British, an invasion of northwestern Europe would come only as a final knock-out blow. First the German Wehrmacht had to be worn out by fighting on many fronts. The Americans contended that the Allies should be using the Clausewitzian principle of concentration of their forces at the decisive point. Their dispute was never resolved and repeatedly hampered the successful course of the Normandy campaign.

Overall Brooke did not believe that the Wehrmacht would be sufficiently weakened before 1944. Furthermore he doubted that US war production would be able to turn out the huge quantity of goods required for an invasion or that America could train an adequate number of troops before this date.

Above all Brooke believed that the way to victory was to conduct a war of attrition. This strategy had been the linchpin for the Allied victory in the First World War. He continued to preach this attritional doctrine throughout the Second, much to the annoyance of Churchill and US war leaders. This perspective had a clear impact on the final British army ground campaign in Normandy.2

Montgomery’s “Plan”

On 15 May 1944, a dazzling array of commanders and leaders gathered at St. Paul’s School in West London for the final full-scale briefing. Because General Dwight D. Eisenhower had appointed General Sir Bernard Montgomery the temporary ground commander for the initial phase of the OVERLORD operation, he was designated to do the main briefing. In this presentation and in his 8 May planning document, Montgomery emphasized that the Allies must quickly move forward and keep the initiative.

He stressed that the main D-Day objective of the Second British Army was to take Caen. “Once we can get control of the main enemy lateral [corridor], Granville-Vire-Argentan-Falaise-Caen, and the area enclosed in it is firmly in our possession, then we will have the lodgement area we want and can begin to expand,” he assured his audience.3

The army that quickly gained control of this Caen-Falaise corridor would control the battle. This was borne out by subsequent events. A slow, safe advance would give Rommel the time he needed to reinforce and shift his troops across the battlefront to keep the Allies contained inside their bridgehead.

For the Allies the very boldness of Montgomery’s plan to take and hold Caen on D-Day ensured its failure. Max Hastings termed it “a substantial strategic misfortune.”4 The overall failure of British senior commanders to warn their assaulting forces of the presence of the German Twenty-First Panzers was inexcusable. Could they have reinforced the British Third Armoured Division and better orchestrated the landings by delivering a stronger combined armor-infantry Caen assault on D-Day? The fact that these alternatives were not even considered is evident by examining Montgomery’s diary and papers from early June 1944.5

After 6 June, Montgomery makes no mention of his initial failure to take the city. As historian Carlo D’Este states, “To have taken, [Caen] according to plan…would have needed…some sort of miracle.”6 Monty’s failed plan to capture Caen on D-Day stalled the entire Normandy campaign.

Montgomery’s Mind Games

On 11 June, Montgomery made his first attempt to disguise a change in his own plan when he informed General Alan Brooke that “my general policy is to pull the enemy on to Second Army [British and Canadian] so as to make it easier for First Army [American] to expand and extend the quicker.”7

Eisenhower thought that Monty’s 11 June message was an admission that his original plan had been nullified by the Caen failure. Ike interpreted this British switch to the defensive as Montgomery’s reversion to his previous battlefield behavior of over-caution and reluctance to risk heavy casualties. At that time whatever Monty’s intention, it was not clear to the other Allied commanders.

Until Montgomery’s 11 June invention of his new strategy, he had always made it perfectly clear that D-Day required an initial aggressive thrust that gained more ground and broke through the German defenses to take Caen. British and Canadian armored forces would rapidly move onto the Falaise plain, then toward the Seine and Paris. This was Montgomery’s original planned “feint” at Caen that would draw the German panzers into a battle highly favorable to the Allies. Overwhelming British and American air superiority and the mobility of their much larger armored forces would destroy any German counteroffensive. This “feint” in turn would assist a faster American breakthrough in support of the British. The Americans would largely bypass the bocage country and help flank the German positions along the coast, forcing their general retreat to the Seine.

It was only after D-Day that this new 11 June strategy became his plan. None of Montgomery’s pre-invasion planning, reports, or presentations ever suggested that the British would stop short of attacking and quickly taking Caen. Thus Montgomery opened the door to what became a long battle of attrition in Normandy.8

It took the British and Canadian forces six battles over forty-two days—from 6 June to 18 July —to capture all of Caen. What was behind Montgomery’s thinking that might help explain his slowness in taking the city? Why had he suddenly shifted the “plan” from a British- and Canadian-led offensive breakout strategy to one of attrition warfare?

The United Kingdom was reaching the end of its manpower reserves. Churchill feared that the manpower situation would diminish his influence with Roosevelt and his status in the “Big Three Conferences” with Roosevelt and Stalin then deciding the postwar future of Europe.

Montgomery believed that a major sustained British offensive to take Caen would lead to heavy casualties. Instead, throughout June, July, and early August, he mounted a whole series of limited attacks. In the long run, Monty’s attrition strategy failed. The failure to take Caen quickly stalled the entire Allied offensive and resulted in heavy British infantry casualties. Montgomery became an “attrition general” who paradoxically could not afford to fight attrition battles. In the long run, his strategy failed.

By 17 July, British and Canadian losses were 37,563. Though actual D-Day casualties had been fewer than expected, the situation went rapidly downhill afterwards. British infantry casualties were eighty percent higher than estimated, with fewer and fewer available replacements.

The set-piece battle was the forte of Montgomery and many other British and American commanders. At Caen and afterward to the end of the war, Monty’s limitation was his lack of quick exploitation to follow up rapidly on battlefield success.

Montgomery’s operational approach was a holdover from his First World War experience on the Western Front—use a “colossal crack” to hit the enemy with devastating modern firepower. This strategy proved to be very misleading for his Allied partners. Time and time again at Caen, for closing the Falaise gap, in the planning and execution of the MARKET GARDEN campaign, and in opening the port of Antwerp, Montgomery seemed to promise the desired breakthroughs but delivered much less.9

Soldier Morale, Training, and Performance

Montgomery’s set-piece battles around Caen and elsewhere usually resulted in some penetration by forces under his command, but they were repeatedly held back from gaining a breakthrough. This was attritional warfare at its worst that began to break down the fighting spirit of the troops.10

Both the United Kingdom and Canada began the Second World War with small professional armies. Their career officer corps was still much weakened by the devastating losses of the First World War. Huge numbers of citizen soldiers had to be conscripted and trained. The OVERLORD operation was their first combat experience. Their training, however, failed to prepare them for combat in Normandy’s difficult bocage terrain and against a determined and more experienced German army. Although many individual soldiers showed outstanding bravery and self-sacrifice in combat, their attacks have been frequently characterized as sluggish.

Casualties among infantry officers were very high. One new officer who was among a group being sent as replacements to a unit that had just been involved in heavy combat reported that a British major announced, “Gentlemen, your life expectancy from the day you join your battalion will be precisely three weeks.”11

Combat fatigue was a significant problem in veteran British army units. This was true even among Montgomery’s “Desert Rats”: the Fifty-first Highland Division, Fiftieth Northumbrian, and Seventh Armoured. They were frequently overcautious and lacked the elan of fresh troops. Many began to feel they had done their fair share of the fighting, and it was for someone else to do the job left. Brigadier James Hargest, a New Zealand observer attached to the 50th Division, offered this evaluation: “The morale of…officer and soldier is not high….[This] applies to new…troops and veterans….Even senior officers grumble about being too long in the line….they are being ‘used.’”12

While the Canadian troops suffered from inadequate training, their overall enthusiasm, higher morale, and quickness to learn battlefield lessons were impressive. Poor leadership by officers, however, led to heavy casualties and frequent tactical battlefield failure.13 General Charles Foulkes, commander of the Second Canadian Infantry Division, freely admitted that his officers and men were ill-prepared in Normandy: “At Falaise and Caen… when we bumped into battle-experienced German troops, we were no match for them.”14

Fitness to Lead and to Fight

By the beginning of July, the Allied invasion had deteriorated into a stalemate. Allied casualties began to resemble the trench warfare losses of the First World War. By 30 June the British Second Army had suffered 24,698 casualties, and this rose to more than 46,000 (excluding combat-fatigue cases) by 25 July.15

Montgomery’s generalship was in great measure to blame. His boss and mentor Brooke also condemned the alarming weakness in the British officer corps: “Half of our Corps and Divisional Commanders are totally unfit for their appointments, and yet if I were to sack them I could find no better. They lack character, imagination, drive and power of leadership.”16 The rapid expansion from a small peacetime army had stretched the quality of the British officer corps to its breaking-point.

Montgomery had limited confidence in his Second Army commander Lieutenant General Miles Dempsey and practically none in First Canadian Army commander General Henry Crerar, whose leadership he dismissed as inadequate. As a result, Monty intervened in their field operations, thus undermining their performance and self-confidence. Precious time was wasted. Battlefield opportunities slipped by unexploited. The Germans were given breathing space to regroup.

Leadership Failures Prolong the War

The failure of Montgomery’s uncharacteristically aggressive plan to take Caen on D-Day unleashed a cascade of problems for a breakthrough from the Normandy beachhead. Reversion to a war of attrition led to higher casualties and weakened morale. In many cases, inexperienced Allied forces faced battle-hardened German troops. Brooke’s and Montgomery’s lack of confidence in the British and Canadian officer corps meant that decisions had to be referred to Montgomery, which denied forces the ability to take advantage of opportunities in fluid combat situations. The Normandy campaign was a tough proving ground for the Allies. While many lessons were learned, this did not extend to the top leadership. Everyone makes mistakes; the key is to learn from them. Unfortunately, Montgomery did not, and he was allowed to keep his position as temporary ground commander far too long. Monty continued to exhibit a lack of aggression in key tactical situations, and his egotism continually led him to cover up the failure of his strategic plans. He and the other Allied leaders could and should have done better.

The Normandy campaign led to the Allied victory in Europe in 1945. Historian Martin Blumenson related what General George Patton said afterwards: “Patton believed his superiors had won the war the wrong way. They had been much too slow.”17

Endnotes

1. Carlo D’Este, Decision in Normandy (Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky, 1994), p. 32.

2. Edward E. Gordon and David Ramsay, Divided on D-Day: How Conflicts and Rivalries Jeopardized the Allied Victory at Normandy (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2017), pp. 21–26.

3. William Weidner, Eisenhower and Montgomery at the Falaise Gap (New York: Xlibris, 2010), p. 262.

4. Max Hastings, Overlord: D-Day and the Battle for Normandy (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1984), p. 121.

5. D’Este, p. 149; Bernard Law Montgomery, Normandy to the Baltic (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1948), pp. 116–34.

6. D’Este, p. 144.

7. Stephen Brooks, ed., Montgomery and the Battle of Normandy (Stroud: History Press, 2008), p. 129.

8. Gordon and Ramsay, pp. 171–72.

9. Ibid., pp. 201–08.

10. C. J. Dick, From Victory to Stalemate: The Western Front, Summer 1944 (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2016), p. 37 and p. 62.

11. Antony Beevor, D-Day: The Battle for Normandy (New York: Penguin Books, 2009), p. 281.

12. D’Este, p. 282.

13. Dick, p. 63 and p. 66.

14. Charles Perry Stacey, The Victory Campaign: The Operations in Northwest Europe 1944–1945 (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1960), p. 276.

15. Beevor, p. 263; Dick, p. 62.

16. Alex Danchev and Daniel Todman, eds., War Diaries, 1939–1945: Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke (London: Phoenix Press, 2001), p. 243.

17. Martin Blumenson, The Battle of the Generals (New York: William Morrow, 1993), p. 272.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.