Finest Hour 181

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – “A Bloody Awful Row”

September 19, 2018

Finest Hour 181, Summer 2018

Page 48

Review by W. Mark Hamilton

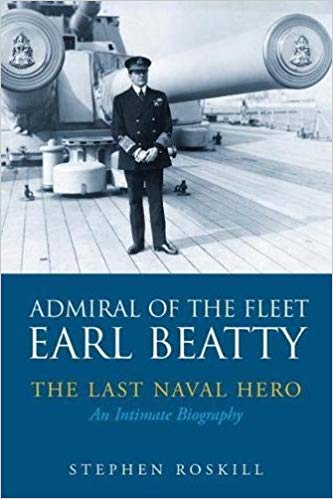

Stephen Roskill, Admiral of the Fleet Earl Beatty: The Last Naval Hero— An Intimate Biography, Seaforth Publishing, 1980 (reprint, with a new introduction by Eric Grove, 2018), 430 pages, £16.99/$29.95. ISBN 978-1526706553

W. Mark Hamilton is author of The Nation and the Navy: Methods and Organization of British Naval Propaganda, 1889–1914 (1986).

Seaforth Publishing and British naval historian Eric Grove are to be congratulated for reprinting Stephen Roskill’s Admiral of the Fleet Earl Beatty. The timing is especially appropriate as the world observes the centennial of the First World War and the historic Battle of Jutland.

Grove’s new introduction is informative and interesting: he comments on recent scholarship since the original publication of Roskill’s biography in 1980 as well as on the contents of the book. He gives special attention to the controversy surrounding the Royal Navy’s substantial losses at Jutland and Roskill’s erroneous conclusion that the primary blame be accorded to defects in ship design, as opposed to the current scholarship ascribing the losses to poor handling of ammunition.

Grove is critical of Admiral David Richard Beatty’s performance in the Battle of Jutland, in regard to both poor gunnery and various signaling issues. For Grove, Beatty must be viewed as careful and cautious at Jutland but no more at fault than Admiral John Jellicoe, who was blamed for his less than aggressive actions in the North Sea. In fact, Grove’s introduction contends that Beatty’s “Whitehall skills,” or political abilities, were more to be admired than his command at sea. Finally, Grove is critical of what has been revealed as Beatty’s efforts to influence the writing of Jutland’s history to favor his own actions.

At the same time, however, Grove praises Roskill’s use of materials from Beatty’s energetic love of life, especially from his mistress, Eugenie Godfrey-Faussett. For Roskill, Beatty is defined by the Royal Navy, polo, blood sport, and the women in his life—of which there were probably many in addition to his wealthy American heiress wife Countess Ethel Beatty.

Despite the flaws that can be seen in hindsight, Roskill’s biography of Beatty remains the strongest to date. Beatty was the most charismatic officer in the Royal Navy in the early twentieth century—widely admired and liked by his fellow officers, the lower deck, and his monarch King George V. Beatty’s good looks, his engaging personality, and his wife’s fortune allowed him to move in the highest social circles and to become the youngest British admiral since Lord Nelson, and later Commander of the Grand Fleet and First Sea Lord.

Beatty had a long and generally good relationship with Winston Churchill going back to the Sudan campaign (1896–98) when, if the legend is true, he gave a bottle of champagne to Churchill by tossing it from ship to shore. Churchill— along with most of high society— was familiar with Beatty’s fearlessness and success on the polo fields, commenting that Beatty’s special abilities allowed him “to view questions of naval strategy and tactics in a different light from the average naval officer.”

In 1912, as First Lord of the Admiralty, Churchill appointed Beatty Naval Secretary and brought him along for cruises on the Admiralty yacht Enchantress. A bond of affection grew between the two men. But Beatty chafed at the formal entertaining required of the Naval Secretary, and in 1913 Churchill gave him command of a battle cruiser squadron, promoting him ahead of many other qualified naval officers. Beatty’s advice for getting along with Churchill was, “You have to have a bloody awful row with Winston once a month and then you are all right.”

With the coming of war in August 1914, Beatty was not always uncritical of Churchill, and he thought Admiral Christopher Cradock had not been fairly judged after the Coronel disaster. Beatty admired Cradock and thought Churchill and the Admiralty were in fact partly to blame for the Royal Navy defeat.

In May 1915, Beatty wrote his wife with concerns about the working relationship between Admiral Sir John Fisher and Churchill. After the disastrous failure of the Dardanelles Campaign, the tension between the two men was substantial. Beatty thought Fisher would survive, but in the end, both Fisher and Churchill would go.

It is at the Battle of Jutland that Beatty comes into full view, and Roskill supports his performance, contrary to the judgment of historian Arthur J. Marder. The Roskill–Marder historical feud is a feature of the book. Beatty himself stated on the first anniversary of Jutland that it was not a day for celebration but “a day for sackcloth and ashes.”

With the conclusion of the war, Beatty was awarded £100,000 by Churchill and the Cabinet, with Churchill commenting, “If he wants it.” Beatty went on to become the longest-serving First Sea Lord and attended the 1922 Washington Naval Conference, which is now seen as a watershed for British naval supremacy. Though he clashed with Churchill over the financial cuts to the Royal Navy, their relationship remained friendly.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.