Finest Hour 179

The British Bulldog and the Little Tramp: Winston Churchill and Charlie Chaplin

June 14, 2018

Finest Hour 179, Winter 2018

Page 16

By Bradley P. Tolppanen

Bradley P. Tolppanen is author of Churchill in North America, 1929: A Three Month Tour of Canada and the United States (2014). The original version of this article appeared in FH 142. It has been revised and updated.

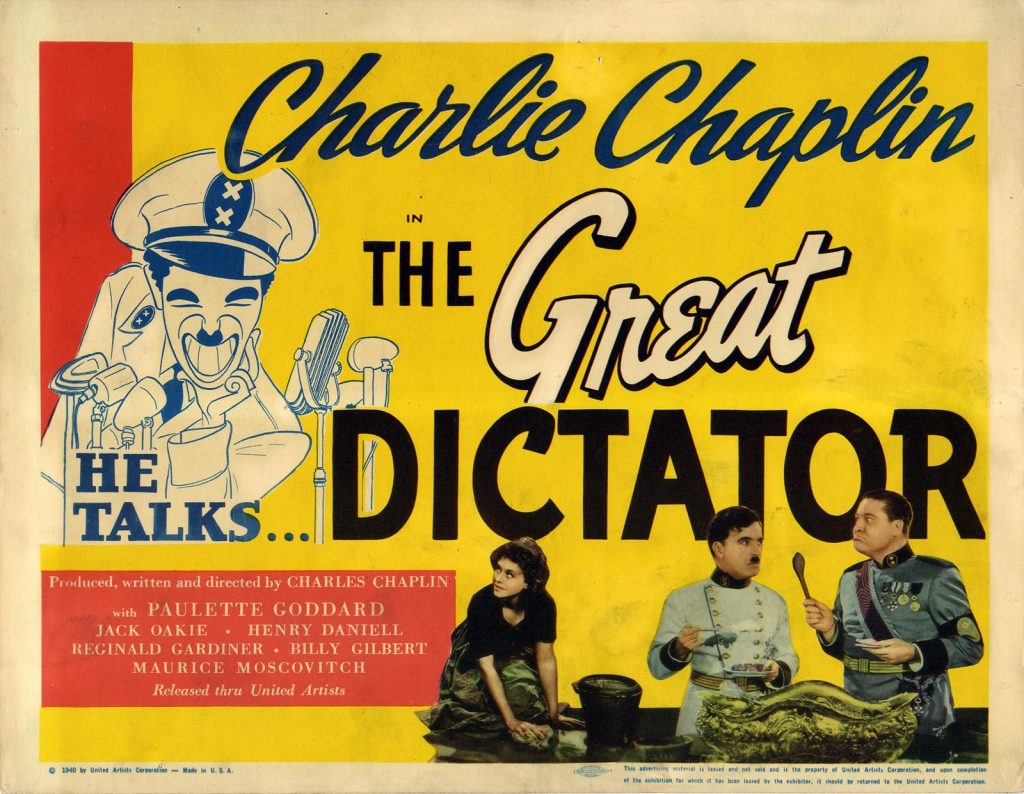

On 14 December 1940, as Britain struggled alone against a triumphant Nazi Germany, Winston Churchill briefly set aside his heavy responsibilities to watch with his family and advisers Charlie Chaplin’s new film The Great Dictator. They were at Ditchley Park in Oxfordshire, which was placed at the Prime Minister’s disposal by its owner Ronald Tree MP, on nights when the full moon made Chequers, the PM’s official country house in Buckinghamshire, too inviting a target.

An avid film lover, Churchill naturally enjoyed this pre-release viewing lampooning Hitler, which starred and was directed by an old friend. The Prime Minister laughed throughout, especially the scene where two dictators throw food at each other. After it ended, Churchill returned to composing another secret cable to President Roosevelt.

Hollywood Sojourn

Churchill had met Chaplin more than a decade earlier, during a tour of North America shortly after the Conservatives had been defeated in the 1929 general election. Despite sharp political differences, Churchill and Chaplin had come to admire and appreciate each other’s qualities, and Chaplin had twice been Churchill’s guest at Chartwell.

2024 International Churchill Conference

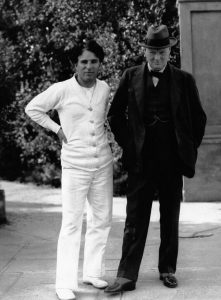

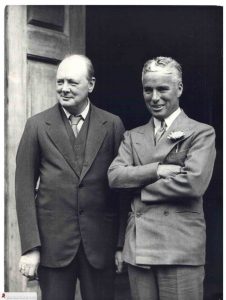

These photographs show Churchill’s 1929 trip to California. The “Churchill Troupe” visited Chaplin in Hollywood. Though initially put off by each other, Churchill and Chaplin became lifelong friends.

These photographs show Churchill’s 1929 trip to California. The “Churchill Troupe” visited Chaplin in Hollywood. Though initially put off by each other, Churchill and Chaplin became lifelong friends.

Accompanying Churchill on his 1929 trip to the United States and Canada were his son Randolph, brother Jack, and nephew Johnny—a foursome which its leader dubbed the “Churchill Troupe.” The troupe was hosted in southern California by newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst and introduced to the city’s film industry, which Churchill later called “a strange and an amusing world.”1 The Churchill men attended receptions in their honor, toured movie studios, and met several film stars, including the actress Marion Davies, Hearst’s long-time mistress.

Davies, whose parties were legendary, quickly arranged for the Churchills to be entertained at a star-studded festivity. It was probably she who convinced her close friend Charlie Chaplin to come. The other celebrities were delivered by Hearst, who had told Randolph and Johnny to prepare a list of all the stars they wished to meet and leave it to him. The only notable to elude them was the reclusive Greta Garbo.

On 21 September, after a day of touring Los Angeles, the Churchill Troupe motored north to Ocean House, Davies’ opulent mansion in Santa Monica. After bathing in the heated Italian marble swimming pool, the troupe dressed for a dinner with sixty glitterati, including Mary Brian, Billie Dove, Bessie Love, Bebe Daniels, Dorothy Mackaill, Wallace Beery, Harold Lloyd and Pola Negri. The most famous guest, however, was Chaplin.

The Little Tramp

After a Dickensian childhood in London, Chaplin had built a long career as a comedian and filmmaker. Declared by some newspapers the most famous figure in the world, he was known to millions through his performances as the “Little Tramp.”

Chaplin was milling about with other guests when Churchill arrived, accompanied by Hearst. Chaplin recalled the future prime minister standing apart, “Napoleon-like with his hand in his waistcoat” as he watched the dancing.2 Since Churchill appeared lost and out of place, Hearst waved Chaplin over and introduced him to the English statesman.

At first Chaplin found Churchill abrupt in manner, but when he started talking about Britain’s new Labour government Churchill brightened. “What I don’t understand is that in England the election of a socialist government does not alter the status of a King and Queen,” Chaplin remarked. “Of course not,” Churchill replied with a quick glance that Chaplin thought “humorously challenging.” “I thought socialists were opposed to a monarchy,” Chaplin persisted. “If you were in England we’d cut your head off for that remark,” Churchill countered with a laugh.3

The dinner party was a great success. Davies persuaded Chaplin to join her in impersonations. She did Sarah Bernhardt and Lillian Gish; he played Napoleon, Uriah Heep, Henry Irving, and John Barrymore as Hamlet. The Davies-Chaplin duo then performed a complicated dance during which Johnny Churchill noticed that Charlie’s feet were small enough to fit into Marion’s shoes. In a sure sign of favor, Churchill kept Chaplin up talking until three in the morning. He wanted Chaplin to take on the role of a young Napoleon as his next film; if Chaplin would do it, Churchill promised to write the script.

“You must do it,” Churchill pressed, describing the opportunities the role presented for drama and comedy. “Think of its possibilities for humour. Napoleon in his bathtub arguing with his imperious brother who’s all dressed up, bedecked in gold braid, and using this opportunity to place Napoleon in a position of inferiority. But Napoleon, in his rage, deliberately splashes water over his brother’s fine uniform and he has to exit ignominiously from him. This is not alone clever psychology. It is action and fun.”4

Growing Friendship

Randolph Churchill had not immediately recognized Chaplin, but wrote in his diary that the actor was “absolutely superb and enchanted everyone.”5 Chaplin, for his part, was impressed by Randolph’s father, whom he thought dynamic with “a thirst for accomplishment” as well as a wonderful talker who could “rattle off brilliant epigrams.”6

Chaplin met Churchill several more times during the troupe’s Los Angeles visit, including an evening when he dined with the Churchills in their suite at the Biltmore Hotel. The actor spent a delightful evening listening to Winston and Randolph pleasantly bantering.

On 24 September, Chaplin hosted the Churchill party at his studio at Sunset Boulevard and La Brea Avenue. After lunch, Chaplin showed them around and provided a private screening of his 1918 film Shoulder Arms, one of his great movies, followed by the rushes for his upcoming silent classic City Lights. As Chaplin always liked to film the visitors to his studio, the troupe’s visit was captured on film. The footage shows “a rather self-conscious and wooden Winston walking beside an assured and relaxed Chaplin.”7 (See the January 2018 Churchill Bulletin for a link to the film.)

Churchill and Chaplin discussed the revolution in progress by the introduction of “talkies.” Chaplin acknowledged the popularity of the new form but was unwilling to concede the demise of silent film, which he called the true “genius of drama.”8 Churchill said City Lights was Chaplin’s attempt to prove silent films superior to talkies, and predicted an “easy victory” for the production.9

That evening the Churchills and Chaplin accompanied Marion Davies to the premiere of Cock-Eyed World at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, where a crowd had gathered for hours. The hoopla did not prevent Randolph from loudly denouncing the film as the worst he had ever seen. Davies apparently forgave him, hosting a dinner at the Roosevelt Hotel where sherry and champagne were served despite the strictures of Prohibition.

A few days later, after leaving Los Angeles, Churchill recounted his fascination with Chaplin: “a marvelous comedian—bolshy in politics & delightful in conversation.”10

Chaplin at Chartwell

In February 1931, Chaplin came to England for the premiere of City Lights. Welcomed by excited crowds, he met a host of public figures and lunched at Chequers with Labour Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald.

Inevitably Chaplin was invited to Chartwell. Churchill asked his onetime Parliamentary Private Secretary Robert Boothby to accompany the actor from London on the 25th. Chaplin brought along his friend Ralph Barton, an artist and cartoonist.

The party arrived on a bitterly cold evening, but Chaplin thought Chartwell a beautiful country residence, “modestly furnished, but in good taste with a family feeling about it.” He bathed and dressed in Churchill’s own bedroom, noticing that it was piled high with papers and had books stacked against every wall. Among the volumes were a set of Plutarch’s Lives, Parliamentary Debates (Hansard), and several books on Napoleon. Chaplin mentioned the latter to Churchill, who replied, “Yes. I am a great admirer of his.”11

Along with Boothby, Churchill had invited Brendan Bracken. Though Clementine Churchill was away, Jack and Johnny Churchill were on hand to meet Chaplin once again, along with two of Winston’s daughters Diana, then twenty-one, and eight-year old Mary, who was allowed to stay up for the occasion by what her father termed a “special arrangement.”12

The evening had a difficult start when Chaplin remarked that Britain’s return to the Gold Standard in 1925 (under Churchill as Chancellor of the Exchequer) had been a great mistake and then launched into a long soliloquy, which Johnny Churchill deemed “pacifist and communist.”13 Winston fell into a moody silence, and Johnny felt badly for Chaplin.

But the actor was himself no mean judge of human reactions. Suddenly changing course, he began to perform. Sticking forks into two bread rolls, he did a dance from his film Gold Rush. The ice melted, everyone relaxed, and an enjoyable dinner ensued. Chaplin thought the evening “dialectic,” as Churchill harangued his guests with humor and wit.14

In a momentary lapse back into contentious subjects, Bracken declared Gandhi a “menace” to the peace in India. Chaplin replied forcefully that “Gandhis or Lenins” do not start revolutions but are forced up by the masses and usually voice the want of a people. (Later in the year, Chaplin would visit Gandhi in London.) “You should run for Parliament,” Churchill said with a laugh.15

“No, sir, I prefer to be a motion picture actor these days,” Chaplin replied. “However, I believe we should go with evolution to avoid revolution, and there’s every evidence that the world needs a drastic change.” He later noted that both he and Churchill were all for progressive government, and that even Churchill believed much had to be done to preserve civilization and guide it safely back to normal after the Depression ended.16

To his wife, Churchill wrote that Chaplin had been “most agreeable” and had performed “various droll tricks.” Both Churchill daughters enjoyed the actor’s performances, young Mary being “absolutely thrilled.”17

Return to Chartwell

Two nights later Chaplin premiered City Lights in London at the Dominion Theatre. Churchill probably did not attend the film, but was present at a party for 200 guests afterwards at the Carlton Hotel. Here Churchill proposed the toast, saying Chaplin was “a lad from across the river” who had “achieved the world’s affection.”18

From London, Charlie Chaplin made a triumphal tour across Europe, opening City Lights to enthusiastic crowds in Vienna, Berlin, and Paris. He probably met and lunched with Churchill at Biarritz in August, where Churchill had arrived on a research trip for his biography of his ancestor John Churchill, the First Duke of Marlborough.

The following month, with both men back in England, Chaplin again visited Chartwell, probably arriving on Friday, 18 September, and staying through Sunday. Clementine was present, along with all the Churchill children this time and other guests. Sarah Churchill, who had missed Chaplin’s previous visit, unlike her sisters, said she was surprised by the actor’s appearance: a “rather good-looking, desperately serious man with almost white hair.”19

At lunch that weekend Churchill attempted to talk about films and acting, but Chaplin was again eager to discuss politics, a disappointment to the others at Churchill’s so-often-political table. Eventually WSC asked what Chaplin’s next role would be. “Jesus Christ,” Chaplin replied with all seriousness. After a pause Churchill asked, “Have you cleared the rights?” There was a silent pause before Clementine returned the conversation to politics.20

Chaplin was amused by Churchill’s family sitting unmoved at the table while WSC held forth, despite being interrupted by telephone calls from Lord Beaverbrook and other demands. During the visit, Chaplin expressed interest in Churchill’s hobbies of painting and bricklaying. Examining one of his host’s paintings over the fireplace in the dining room, Chaplin said, “But how remarkable.” Churchill replied: “Nothing to it—saw a man painting a landscape in the South of France and said, ‘I can do that.’” On a stroll along the brick walls Churchill had constructed, Chaplin remarked that bricklaying must be difficult. “I’ll show you how and you’ll do it in five minutes,” said his host. And he did.21

Just before Chaplin left, he asked, “Is there a walking stick?” He was directed to a cupboard, only to emerge moments later with a bowler hat and stick, instantly transformed from the serious guest to the endearing “Little Tramp.” His “enchanting performance” impersonating other actors included his John Barrymore in Hamlet’s “To Be or Not to Be”—while picking his nose! “The day was made for us,” Sarah wrote, “and we were sorry to see him go.”22

Chaplin, who had really come to know Churchill on this visit, concluded that WSC had a charming family, lived well and had more fun than most people. Although poles apart politically, Chaplin considered him a “sincere patriot” who had played for the highest stakes and had sometimes won, though his friend’s political future was at that time doubtful.

Envoi

A final, brief meeting between Chaplin and Churchill occurred years later on 25 April 1956 after Churchill had retired and Chaplin was living in Switzerland. They met at the Savoy Grill in London: a rather strained encounter, Chaplin said, because he had failed to respond to a letter Churchill had sent congratulating him on his film Limelight two years before.

Chaplin told Churchill he thought his letter was charming but did not think it required a reply. Somewhat mollified, Churchill accepted his explanation, adding, “I always enjoy your pictures.”23

Endnotes

1. Winston S. Churchill, “Peter Pan Township of the Films,” Daily Telegraph, 30 December 1929.

2. Charlie Chaplin, My Autobiography (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1964), p. 339.

3. Ibid.

4. Charles Chaplin, “A Comedian Sees the World,” Woman’s Home Companion, 60:10, October 1933.

5. Randolph S. Churchill, Twenty-one Years (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965), p. 83.

6. Chaplin, “A Comedian Sees the World.”

7. Bradley Tolppanen, Churchill in North America, 1929: A Three Month Tour of Canada and the United States (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2014), p. 176.

8. Winston Churchill, “Peter Pan Township.”

9. Martin Gilbert, ed., Winston S. Churchill, Companion Volume V, Part 2, The Wilderness Years 1929–1935 (London: Heinemann, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981), p. 97.

10. Richard M. Langworth, Churchill by Himself (London: Ebury Press, 2008), p. 331.

11. Chaplin, My Autobiography, pp. 340–41.

12. Gilbert, p. 282.

13. John Spencer Churchill, A Churchill Canvas (Boston: Little Brown, 1962), p. 133.

14. Chaplin, “A Comedian Sees the World.”

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid.

17. Gilbert, p. 282.

18. Chaplin, My Autobiography, p. 345.

19. Sarah Churchill, A Thread in the Tapestry (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1967), p. 35.

20. Ibid.

21. Chaplin, My Autobiography, pp. 340–41.

22. Sarah Churchill, pp. 35–36.

23. Chaplin, My Autobiography, p. 484.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.