Finest Hour 179

Love, Self-Sacrifice, and Whomping the Bad Guys: Winston Churchill’s Favorite Films

April 15, 2018

Finest Hour 179, Winter 2018

Page 22

By Robert James

Robert James received his Ph.D. in English from UCLA. He is author of the series Who Won?!? An Irreverent Look at the Oscars.

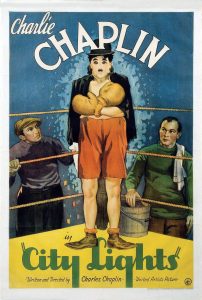

Winston Churchill had excellent taste in movies. His three favorite films have all remained recognized classics, beloved by fans for generations: Charlie Chaplin’s masterwork, City Lights (1931); Alexander Korda’s romance That Hamilton Woman (1941); and Laurence Olivier’s most innovative work as a director, Henry V (1944). City Lights is a strong candidate for the greatest of Chaplin’s films, as well as the height of American silent film. That Hamilton Woman tops the category of the doomed lover genre, as well as being the most enduring of the three films Olivier made with Vivien Leigh. Henry V broke new cinematic ground in adapting Shakespeare, and for many endures as the finest of all Shakespeare films not directed by Orson Welles or Akira Kurosawa. Churchill loved all three of these, and had a hand in either promoting or creating them—or both.

City Lights

Charlie Chaplin was facing disaster aft er Warner Brothers released The Jazz Singer, the first “talkie,” on 26 October 1927. But then, so was all of Hollywood, although it took people time to recognize that—and nobody took longer than Chaplin, the king of the silent screen, the most famous face in the world (even today, people are more likely to recognize Chaplin than any other movie star of the first half of the Twentieth Century—except perhaps Mickey Mouse). Chaplin would go on making silent films long aft er everybody else had converted to sound; he did not release his first true talking picture until The Great Dictator in 1940. He had other tragedies on his hands as well, including the troubled production of The Circus (the sets burned down), his mother’s death, his ugly scandalous divorce from his second wife, and the IRS demanding payment of back taxes.

Chaplin took almost two years to film City Lights, from December 1928 to September 1930, financing the entire production from his own pocket. Not content with merely writing, producing, directing, and starring, he also composed the score for the first time for one of his films (for the female leitmotif, he chose a theme by José Padilla). Musical arrangement was placed in the capable hands of famed film composer Alfred Newman.

Chaplin’s tale of a tramp who falls in love with a blind flower girl, then does all he can to help her, including suffering the crazed attentions of a drunken millionaire, entering the boxing ring, following an elephant, and getting carted off to jail, is one of the most important artistic works of the Twentieth Century. The final moments are arguably the most honestly emotional in the history of film. Churchill’s granddaughter Edwina Sandys told the 2016 International Churchill Conference that her grandfather always cried at the end of the film.

Getting there was not easy; it never was for Chaplin, whose ambitions continually rose. In addition to the aforementioned personal crises, he had to deal with a lead actress, Virginia Cherrill, who was next to impossible at being convincing on screen (she was not convincing as Cary Grant’s second wife either, but that is another story). At one point Chaplin fired her, replaced her with his co-star Georgia Hale from The Gold Rush, then ended up re-hiring Cherrill (for double the money). That she ultimately ends as one of the strengths of the film is almost entirely due to Chaplin’s gift s as a director.

The greatest story bind during City Lights was trying to figure out how to convince the blind girl that Chaplin was a rich man. Chaplin shot the scene more than three hundred times, ultimately sending the entire cast and crew home for days on full pay while he figured it out. Chaplin shot a total of 180 days, out of twenty-two months of production; such is the price of perfection. The film became one of the biggest hits of Chaplin’s career.

Churchill visited the set of City Lights on 24 September 1929, reuniting with his friend. Chaplin was so thrilled he did not shoot the entire day, preferring to entertain Churchill’s party at a luncheon. Chaplin and Churchill toured the sets, pausing for still photographs and the newsreel cameras (see p. 17). Two years later, on 27 February 1931, Churchill attended the world premiere of City Lights in London; George Bernard Shaw was the guest of honor (the film had already premiered in Los Angeles, with Albert Einstein and his wife as Chaplin’s guests). That night, Churchill toasted Chaplin at dinner as “a man who had started out as a lad from across the river and had achieved the world’s affection.” Privately, Churchill summed up Chaplin as a “marvelous comedian—bolshy in politics and delightful in conversation.”1 Chaplin later named Churchill as one of only three geniuses he had ever met, the other two being Einstein and pianist Clara Haskil.

That Hamilton Woman

Churchill had little to do with the creation of City Lights. The question of Churchill’s involvement in 1941’s That Hamilton Woman is more inviting as the source of the film’s inspiration, but far less rooted in actual fact. The historical record is clouded by a conspiratorial tone of Churchill’s supposed involvement as well as producer-director Alexander Korda’s non-cinematic activities in peacetime America between the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939 and the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.

Korda is a legendary figure in the history of British cinema, along with his brothers Zoltan and Vincent (see p. 12). The Kordas were born in Hungary, and emigrated as a result of the postwar political situation (Alexander seems to have been a supporter of the brief Communist takeover). Korda moved into the Austrian and German film communities before heading to Hollywood in the late Twenties, and then to France and Great Britain. He hit the big time as the producer of Charles Laughton’s The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933) and Leslie Howard’s The Scarlet Pimpernel (1934). He then used a script by H. G. Wells to lay out the future of the world in Things to Come (1936); as that film remains seminal to the science fiction genre, so too does his magisterial The Thief of Bagdad (1940) stand central in the development of fantasy and special effects. Korda moved to the United States to complete the Arabian tale, and he then made That Hamilton Woman in the United States as well.

Korda had known Churchill during the politician’s years of political exile, paying him as a script consultant during Korda’s failed attempt to film the life of Lawrence of Arabia, as well as having Churchill provide scenarios for short subjects on political and historical issues. That relationship forms the basis for any speculation that Churchill set Korda to any illicit activities as a British propaganda conduit in America, including inciting Korda to make That Hamilton Woman as a way to jog the Americans out of their isolationism. Unfortunately, this can only be speculation, since no actual proof exists of any kind of specific instigation.

But what can be proven? Three things for certain. First, an obvious parallel is intended between the tale of Lord Nelson fighting Napoleon and the need to fight Hitler, most obviously in Nelson’s speech arguing for continued fighting against Napoleon instead of an ill-advised peace treaty: “Gentlemen, you will never make peace with Napoleon! Napoleon cannot be master of the world until he has smashed us up, and believe me, gentlemen, he means to be master of the world! You cannot make peace with dictators. You have to destroy them, wipe them out!” Very Churchillian that, and a scene essentially replicated in 2017’s Darkest Hour with Gary Oldman as Churchill himself.

The doomed love affair in That Hamilton Woman was intended to draw in both men and women. Casting Vivien Leigh in the aftermath of her smash hit Gone with the Wind and Laurence Olivier in the wake of his impressive hits Wuthering Heights and Rebecca was a smart box-office move. The two stars had finally married and were in the throes of a celebrity obsession on the part of the public (mirrored in later generations by Elizabeth Taylor marrying Richard Burton in the Sixties).

A second fact is that the America Firsters went nuts, accusing Korda of attempting to provoke the US into war with Hitler (they made the same accusation against Chaplin and The Great Dictator, as well as other Hollywood productions). Korda was summoned to testify before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on these accusations, but the attack on Pearl Harbor happened right before Korda was due to be grilled on 12 December 1941 as a suspected British intelligence agent.

The third fact is That Hamilton Woman is widely regarded as Churchill’s favorite film, with accounts of his viewing the movie ranging from seventeen to eighty-three times (oddly enough, at least one source suggests it was also Joseph Stalin’s favorite). Did Churchill suggest the film be made? Certainly, the concept is possible, but no evidence exists to support that claim. What we do know is that he was very much in love with Vivien Leigh. (Well, who wasn’t?) After the war, Churchill gave Leigh one of his best paintings, which she kept in her bedroom for the rest of her life (see FH 177). Churchill also supported Leigh’s efforts to save a historic theatre in the Fifties. Churchill had a fondness for her performance that exceeded his critical faculties (of the three favorites, That Hamilton Woman remains the least regarded by film historians).

We also know that That Hamilton Woman provided a strong historical context for fighting Hitler, and for boosting the morale of the British people. Much of what the film was saying was what Churchill was saying on an almost daily, if not hourly, basis.

As a film, That Hamilton Woman was made remarkably quickly and far more cheaply than one might expect, given the lavish sets and costumes. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences saw fit to nominate the hit for Best Cinematography (for a lovely sense of shadows), Best Art Direction (for Vincent Korda and Julia Heron), Best Special Effects (the naval combat scenes), and Best Sound (for which it won the Oscar). In the wake of its success, Churchill wrote to Alexander Korda on 15 June 1941: “Many congratulations upon your admirable film about Nelson.”2

Henry V

Of the three films discussed here, we know Churchill was a primary force in getting Henry V made, as Laurence Olivier was prompted by Churchill to create a movie that would boost British morale by reminding them of their greatest wartime king. Churchill arranged for government financing of a substantial part of the budget as well. The Prime Minister thought it “would be a rousing film for the country.”3 One is tempted to point at the false anecdote about Churchill being asked to cut funding for the arts, and ending the request with the retort “Then what are we fighting for?” as a perfect summation of Churchill’s attitude about making Henry V.

Olivier had been using speeches from Henry V to entertain the troops (“once more unto the breach” and “We few, we happy few” were particularly apt). He cut the play substantially, emphasizing the patriotic aspects and downplaying the less savory moments of Henry’s character (such as approving of rape as a war tactic—little things like that). Filmed largely in Ireland for the exterior scenes and in England for the interiors, Henry V is a triumph of the creative spirit, as it moves us from a patently false recreation of the Globe and the staging practices of Shakespeare’s day to a more realistic use of sets as one might find on the stage in Olivier’s time, to a completely realistic battle of Agincourt, shot with all the artistry of modern cinematography. From start to finish, Henry V is a truly unique film that was the first completely successful cinematic adaptation of Shakespeare, and it still strikes many viewers as remarkably postmodern in its approach (Olivier would try again with Hamlet though with less acclaimed results, due largely to his unnecessary cuts and a bluntly low-denominator approach to his audience). As a director, Olivier set an impossibly high bar for himself, and one that he would never again come close to equaling.

The score by Sir William Walton is also a classic, and remains a model for this kind of composition. Henry V was a commercial hit as well, garnering Olivier an honorary Oscar for “his outstanding achievement as actor, producer and director in bringing Henry V to the screen,” as well as competitive nominations for him as Best Actor and Best Picture.4 Walton also received a nomination, as did the Art Direction. When Churchill first saw the picture on 25 November 1944, his private secretary Jock Colville recorded: “The P.M. went into ecstasies about it”—right and honorable response.5

Deeply Romantic

Once upon a time, I used to scare people with a parlor game, in which I asked for their three favorite books or movies, the ones they obsessed over. I then proceeded to tell them things about themselves I could not possibly know (I courted my wife this way; she was charmed, which tells you something about both of us). Were I to play this game with Churchill and his three favorites, I would argue he was deeply romantic, enchanted by underdogs, concerned about the difficulties of the heart, and centered on selflessness and self-sacrifice. In short, Winston Churchill was a most admirable human being with a good sense of humor and a love of fair play—but mischievous.

Endnotes

1. Bradley P. Tolppanen, Churchill in North America, 1929: A Three Month Tour of Canada and the United States (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2014), p. 179.

2. Martin Gilbert, ed., The Churchill War Papers, volume III, The Ever-Widening War (Boston: W. W. Norton and Co., 2001), p. 807.

3. Abigail Rokison, “Laurence Olivier,” in Gielgud, Olivier, Ashcroft, Dench: Great Shakespeareans, Russell Jackson, ed. (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), p. 92.

4. http://awardsdatabase.oscars.org/search/results

5. Craig Brown, Hello Goodbye Hello: A Circle of Remarkable Meetings (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013), p. 195.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.