Finest Hour 179

Alexander Korda: Churchill’s Man in Hollywood

April 15, 2018

Finest Hour 179, Winter 2018

Page 12

By John Fleet

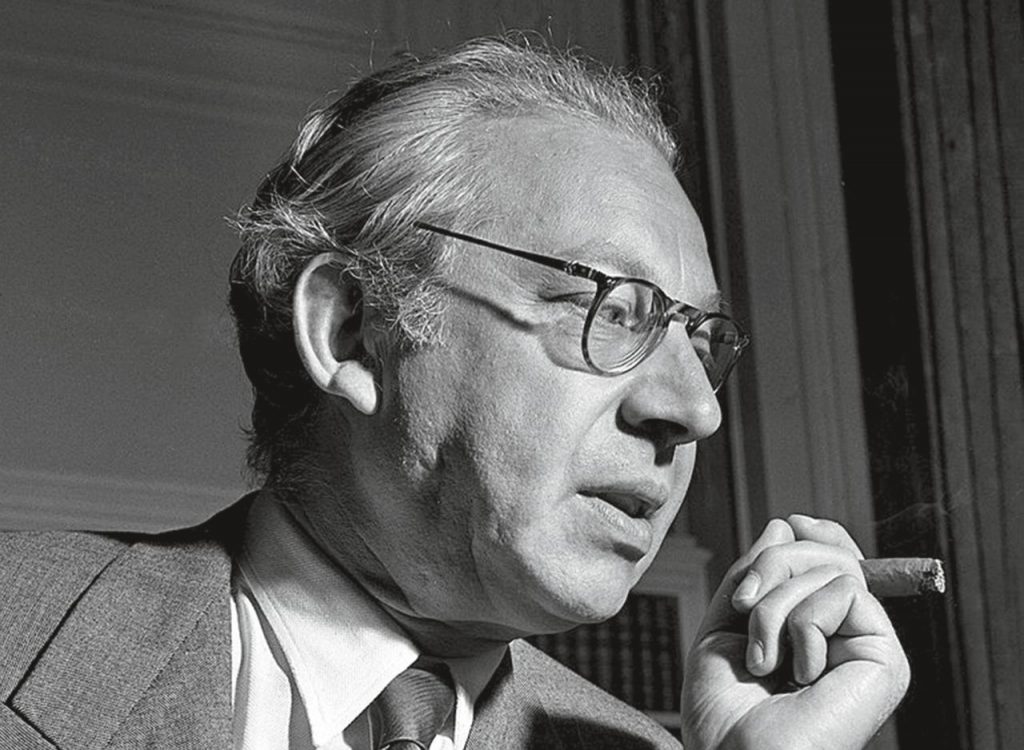

John Fleet is a British film-maker. He is currently making a documentary about Winston Churchill and his friendship with Alexander Korda.

In early 1935, Winston Churchill wrote an urgent letter to the Hungarian-born British film producer Alexander Korda. He had just completed a screenplay entitled The Reign of George V and was anxious that “not another day be lost in the preparation of the sets.”1 So confident was Churchill that he cautioned in the text of his screenplay, “the audience must have a chance to recover from the cataract of impressions and emotions to which they will be subjected.”2

It was to be “an imperial film embodying the sentiments, anxieties and achievements of the British people all over the world.”3 Churchill was under contract to Korda as assistant-producer and historical adviser for a handsome sum, so much so that he had sidetracked his long-overdue biography of Marlborough.

Churchill believed that “with the pregnant word, illustrated by the compelling picture, it will be possible to bring home to a vast audience the basic truths about many questions of public importance.”4

The main problem, however, was that the screenplay showed no concern for budget. Here is how Churchill painted a few of his scenes:

“a German gunboat steaming through the water in a moonlit night…”

“a rapid series of shots of all parts of the Empire…”

“…away to British Columbia for a moment”

Churchill’s sense of visual drama was undeniable, though, imagining how “a skeleton face with its helmet still on fills the picture of a veritable ‘Death’s Head’ growing to monstrous, symbolic proportions.” He did admit in the screenplay, however, that “this terrifying spectacle is our only macabre shot.”

In March 1935, Korda shelved the project, leaving Churchill deflated, “the film is busted and all my hard work wasted.”5 He was, however, greatly impressed by Korda and his team and began a friendship with him that would shape the course of far more than just film history. Writing to his wife Clementine, he said, “Korda certainly gives me the feeling of a genius at this kind of thing…. I have great confidence in this man and in his flair.”6

The Impresario

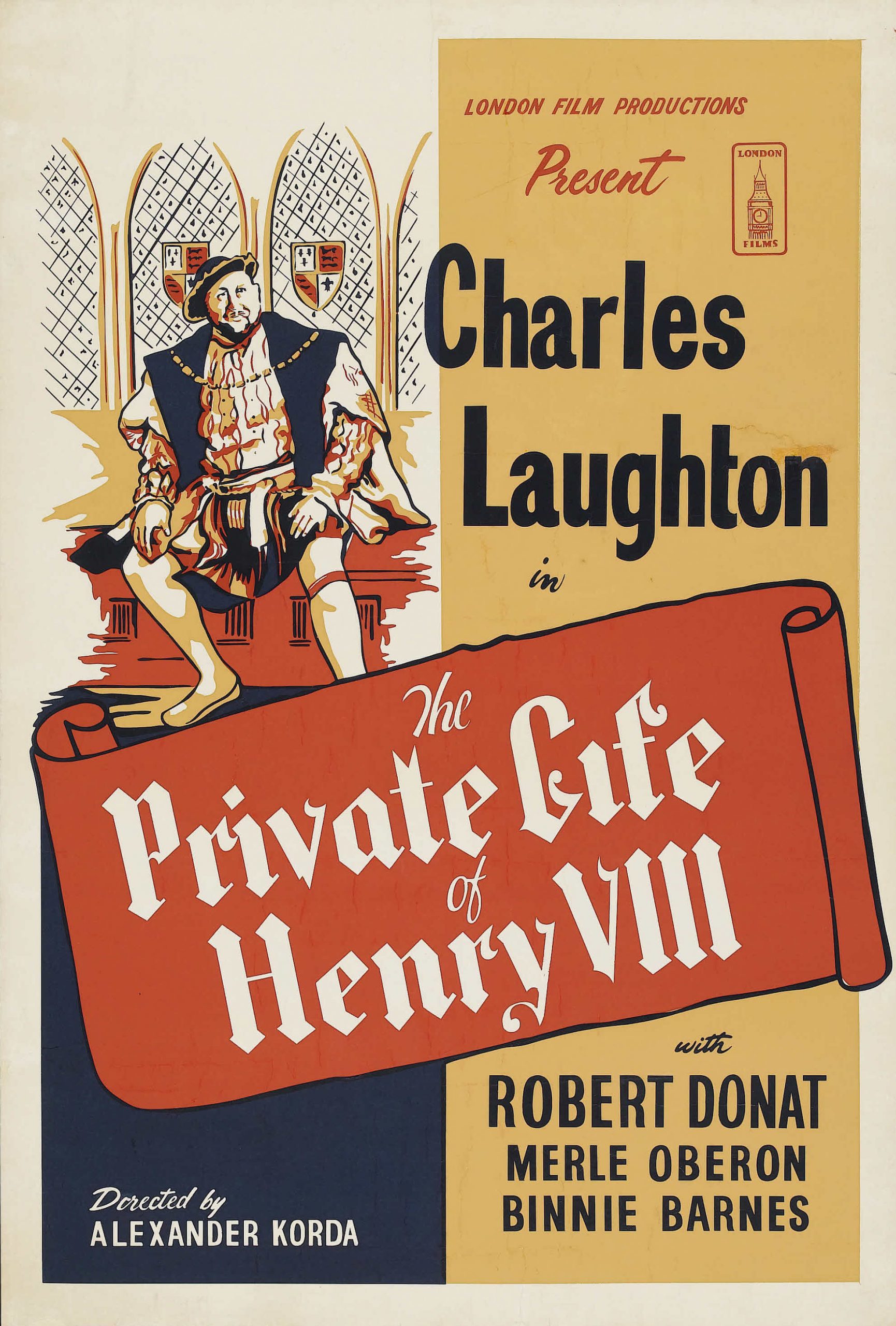

Korda’s box-office smash The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933) had placed him at the centre of a frustratingly modest British film industry, but Churchill could see its potential.

In a 1936 article called “The Future of Publicity,” he wrote that “the pictures are among the most powerful instruments of propaganda the world has ever known.”7 When Korda opened Britain’s first Hollywood-style studio that year, he stated that “Denham is based on the simple belief that the British Empire sooner or later must have its own film studio.”8

Having grown up in poverty in Hungary, Korda was viewed with considerable suspicion on his arrival in Britain. In some people’s eyes he was making a goulash of British history. The Private Life of Henry VIII might have put British films on the map in America, but it painted an embarrassing picture. In a key scene, Charles Laughton devoured a chicken, throwing its bones over his shoulders with the line “refinement’s a thing of the past.”

Churchill cautioned Korda, “my only criticism would be a little less chicken-bone chewing and a bit more England building.”9 This poignant remark would almost become the mission statement of Korda’s company, London Films.

Gloriana

Korda turned next to Henry’s daughter Queen Elizabeth I in a morale-boosting spin. Her victory over the Spanish Armada was one of Churchill’s favourite bits of history and guaranteed to provide the glory he wanted. Instead of chicken bones, there would be the sea-dogs and buccaneers of the Elizabethan era.

In superb casting, Fire over England brought together Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh, sealing another box-office smash and going on to win the League of Nations Award for Best Film in 1936. Its underlying message was that the real menace to peace was in fact “prudence,” or rather—appeasement.

Churchill visited Denham in August 1936, relishing the sight of the miniature Armada, even deciding to stock the pond with swans. Korda’s production managers recorded with exasperation in his diary that “Winston Churchill was with A. K. from 1.45 [to] 3.45!”10 This was England-building at its finest, and an Hungarian Jew fresh off the boat from Hollywood had become its unlikely spokesman.

In a speech, echoed by Churchill in the war, the Queen mounts a horse and delivers screenplay dialogue penned in 1588: “I am come to live or die amongst you all, to lay down for my God and for my Kingdom and for my people my honour and my blood even in the dust. I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and valour of a King and of a King of England too. Not Spain, nor any Prince of Europe shall dare to invade the borders of my realm. Pluck up your hearts, by your peace in camp and your valour in the field we shall shortly have a famous victory.” Churchill’s work as adviser was starting to bear fruit.

English Westerns

As troubles in Europe became ever more apparent, so Korda’s attentions turned to Hollywood. The US withdrawal from European affairs had left a power vacuum for Hitler to fill, and movies were a means of clawing them back.

It was on the tarnished image of the British Empire that Korda now focused his attention, sending film crews to Africa and India to make his Empire trilogy (Sanders of the River, 1936; The Drum, 1938; and The Four Feathers, 1939), cleverly re-fashioning the oppressed natives as comrades in arms. The isolationist Chicago Tribune responded by upping its already vicious anti-Empire campaign. Its owner, Colonel Robert McCormick, believed that British imperialism was more dangerous than Hitler’s fascism. Luckily for Korda, these “English Westerns” were box-office gold. Hollywood was so impressed that studios started to make their own versions such as 1939’s Gunga Din.

Korda’s most colossal creation was The Four Feathers, which brought an episode from Churchill’s early life to the screen. In a helpful budgetary move, the producer mobilised the British army regiment in Khartoum as extras, calling upon 1574 natives, 1578 horses, 300 camels, and ten mules to recreate the battle of Omdurman in blistering Technicolor.

A leader of the America First movement, Charles Lindbergh, became so enraged that he accused “the British and the Jewish” of being responsible for the fact that cinemas “soon became filled with plays portraying the glory of war.”11 The American author, Gore Vidal, a child of the ’30s, wrote an essay called “Fire over England” in which he explained how “the English kept up a propaganda barrage that was to permeate our entire culture…. On our screens, it seemed as if the only country on earth was England…. British Intelligence had no great faith in the American educational system.”12

Mission to Hollywood

In May 1940, Britain’s darkest hour, Korda was called to an urgent meeting with Duff Cooper, Churchill’s Minister of Information, and a plot was hatched. Korda would sail for Hollywood and make what he termed an “American” propaganda film.13 Hollywood was a safe-haven for film-makers. Denham Studios took a direct hit during the Blitz. Furthermore, a film made in Hollywood would arouse less suspicion.

The resulting film, That Hamilton Woman, released in March 1941, was perhaps the most revealing example of Churchill’s involvement in the film world. Casting Laurence Olivier as Admiral Nelson and Vivien Leigh as his lover Emma Hamilton, it told effectively the same story as Fire over England, only this time with Napoleon instead of the Spanish standing in for Hitler. Olivier delivers the line, “you cannot make peace with dictators, you have to destroy them, wipe them out,” in what commentators described as a regular 1941 war speech. Legend has it that Churchill actually wrote it.

In a further bit of movie gold, Vivien Leigh was now the most famous actress in the world after her Oscar-winning turn in Gone with the Wind. Audiences flocked to her next show.

Churchill sent telegrams to Korda during the production, suggesting alternative titles, such as “Emma.” He urged the producer also to include Nelson’s famous saying, “if there were more Emmas, there would be more Nelsons.”14 In contrast to Hitler, who decided to commission a film largely about himself (Triumph of the Will, 1935), Churchill preferred to idolise other people’s achievements.

Churchill kept a bust of Nelson on his desk, and named the British Admiralty cat after him. It is no surprise therefore that it became his favourite film, notching up seventeen viewings, the most notable of which was on board HMS Prince of Wales during his secret meeting with President Roosevelt in August 1941.

The Power to Persuade

The greatest testament to the success of the British mission to Hollywood is that in September 1941, two months before Pearl Harbor, the US Senate launched an investigation into “Propaganda in Motion Pictures,” and Korda’s film was Exhibit One.

Spokesmen for America First warned that the public was susceptible to this kind of propaganda precisely because it was delivered through the medium of cinema. They attacked The Four Feathers, seeing it as another example of “the ancient British sport of knocking off the natives.”15

In truth, though, the charm of the British spirit had been brought to the fore. Churchill then stepped out of the wings and embodied the same romantic notions the cinematic parallels had evoked. He began his “We shall fight them on the beaches” speech with a quick reminder about the moment “when Napoleon lay at Boulogne for a year….”16

Churchill had by then become the lead character in the single most defining drama of the twentieth century. He was the hero with his shining sword, and there was Hitler the dragon who had to be defeated. He was St. George personified, and he played the role far better than any actor has done since. Whether Olivier made a better Nelson we shall never know, but for the newsreel cameramen Churchill did not disappoint.

When he addressed the US Congress in December 1941, he asked rhetorically, “what kind of a people do they think we are? Can it be that they do not realise that we will never cease to persevere against them?”17 If Americans were in any doubt about that, a trip to the cinema would provide all they needed to know.

In Churchill’s George V screenplay, the following line appears: “In all her wars, England always wins one battle—the last.” In 1942, he delivered the same line to tremendous applause, in what he termed “The Bright Gleam of Victory” speech.

Winston Churchill was, however, no actor at all. At twenty-four years old, in the candle-lit barracks of Northern India, he penned an unpublished essay called “The Scaffolding of Rhetoric” in which he analysed what made an effective orator. He cautioned that “before he can move their tears his own must flow.”18 In other words, if the orator is any good, he is not acting at all.

Honours

As the war raged on, the FBI launched an investigation into Korda, eventually questioning him in 1946. They accused him of acting as an agent for the British government, having tracked payments he made to British Intelligence agents in America. The real story behind that is worthy of a screenplay in itself. The deputy-head of MI6, Claude Dansey, appeared on the board of London Films after the war, in convenient timing.

Korda was knighted on Churchill’s orders in 1942. In a letter thanking Churchill, the producer quoted Browning’s poem Trafalgar, “Here and here has England helped me—how can I help England—say.”19 He also gave Churchill the gift of a permanent cinema in the basement at Chartwell (see page 28). Korda went on to cement his place as one of the founding fathers of the British film industry. The Best British Film award at BAFTA is given in his honour.

When Churchill eventually published A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, Korda paid him £50,000 for the film rights, having agreed secretly to do so ten years earlier. The truth was they had already filmed the most exciting bits.

England-building on screen has a long and distinguished history from Korda’s time to the fifty-five-year film franchise that is James Bond. The creator, Ian Fleming, like Korda, worked for Claude Dansey, code-name “Z” or rather “M.”

Korda wrote to Fleming in 1954 about the Bond novel Live and Let Die, “Your book is one of the most exciting I’ve ever read. I could not put it down.”20 He missed his chance of bringing it to film, however, when he died in 1956.

In a great crowd-pleaser, the Bond film The Spy Who Loved Me opens with Roger Moore evading his captors by skiing straight off a cliff, only to pull the rip-cord on a parachute boldly emblazoned with the Union Jack. Chicken-bone chewing had been replaced by martinis— shaken, not stirred. Arguably, the confidence of that scene owes a lot to a pre-war discussion over brandy and cigars between two unlikely friends.

Endnotes

1. Letter from Winston Churchill (WSC) to Alexander Korda (AK), 14 January 1935, CHAR 8/514, Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge (CAC).

2. The Reign of George V screenplay, CHAR 8/526.

3. Letter from WSC to AK, 28 January 1935, CHAR 8/514.

4. Letter from WSC to AK, 24 September 1934, CHAR 8/495/A–B.

5. WSC to Clementine Churchill (CC), 23 January 1935, CHAR 1/273/19–23.

6. WSC to CC, 18 January 1935, CHAR 1/273/8–13.

7. Winston Churchill, “The Future of Publicity,” Collier’s Weekly, CHAR 8/521.

8. C. A. Lejeune, “The Private Lives of London Films,” Nash’s Pall Mall, January 1937.

9. Letter from WSC to AK, 14 January 1935, CHAR 8/514/17.

10. Unpublished diary of David Cunynghame, Production Manager, London Films, 8 August 1936.

11. Speech given by Charles Lindbergh, 11 September 1941, www.charleslindbergh.com/americanfirst/speech.asp.

12. Gore Vidal, Screening History (London: Andre Deutsch, 1992), pp. 31–63.

13. Cunynghame diary, 29 May 1940.

14. Private wire from WSC to AK, page undated—no doubt early 1941, CHAR 2/419/151.

15. Typescript of Hearings before Committee on Interstate Commerce, 9–26 September 1941, pp. 116–30, National Archives, Washington.

16. House of Commons speech, 4 June 1940.

17. Congressional Record, 26 December 1941.

18. Winston Churchill, “The Scaffolding of Rhetoric,” CHAR 8/13.

19. Letter from AK to WSC, 19 June 1942, CHAR 2/443.

20. Fergus Fleming, ed., The Man with the Golden Typewriter: Ian Fleming’s James Bond Letters (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), p. 54.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.