Finest Hour 179

Books, Arts & Curiosities – The Clattering Train

April 28, 2018

Finest Hour 179, Winter 2018

Page 44

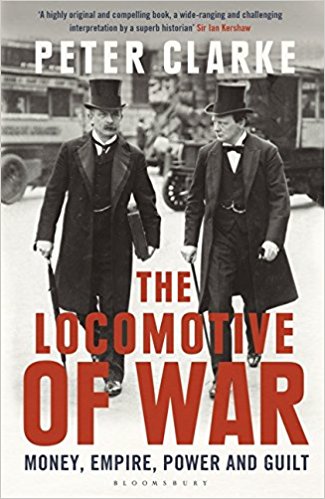

Peter Clarke, The Locomotive of War: Money, Empire, Power and Guilt, Bloomsbury Press, 2016, 418 pages, $30.00. ISBN 978–1620406601

Review by Christopher H. Sterling

Christopher H. Sterling is Professor Emeritus of Media and Public Aff airs at the George Washington University.

This is not a book focused upon Churchill, though the man and some of his writings (chiefly The World Crisis) do figure throughout. Instead, Peter Clarke’s latest history can be read in two ways. In the first instance, the book offers an assessment of the moralistic rhetoric used by national leaders compared with their military and economic actions both before and after the First World War. The second way to read the book is as a series of insightful biographical vignettes of a selection of those leaders. Either way, one’s time is well spent.

A retired professor of history at Cambridge University with numerous prior books to his credit, Clarke takes on the huge and still-expanding literature concerning the causes and effects of the Great War. As its centennial is now being observed, Clarke reaches back to the lives and writings of a key selection of British and American leaders (and one Frenchman—Clemenceau) in order to understand better what happened and why. His argument is that once set on its rails, the initiative or “locomotive” leading to war (the imagery dates to Trotsky) is hard if not impossible to stop.

2025 International Churchill Conference

The first half of the volume consists of an illuminating collection of mini-biographies of such people as Woodrow Wilson, David Lloyd George, Churchill, economist John Maynard Keynes, FDR, and Wilson’s chief adviser, “Colonel” House. Note that two of these— Keynes and Franklin Roosevelt— were leaders-in-training, as it were, operating from junior positions but often exerting greater impact than their official roles might otherwise have indicated (this was especially so with Keynes). The war memoirs of Lloyd George and Churchill take center stage, with much positive comment on the latter and criticism of the former, not least on their readability. For each of the major players, Clarke offers an informed profile, often supplemented by gossipy sidelights to add color (even to the otherwise colorless Wilson).

How these men interacted is the glue connecting the chapters, especially in the book’s second half. As the study progresses, the focus is increasingly on the bitter 1919 battle over German reparations and which nation was to receive what. Keynes made his mark in this process—especially with his 1919 book The Economic Consequences of the Peace. As Clarke makes clear, where money was involved (or to a somewhat lesser degree, domestic politics and imperial concerns), good intentions and international comity quickly gave way.

Clarke’s prologue (going all the way back to Gladstone) and brief epilogue provide the wrapping for the central chapters. The latter suggests ways the arguments over the place of the Great War in national histories was often determined by events in the Second World War. His “notes on sources” essay is much more than that, for it offers an excellent guideline of what else to read on this huge topic, all carefully linked to the arguments made here. Bottom line: Clarke provides a valuable and enjoyable book offering considerable insight on selected Allied decision makers and their varied policy positions before and after the 1914–18 war.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.