Finest Hour 179

Books, Arts & Curiosities – Daemonic Duo

April 29, 2018

Finest Hour 179, Winter 2018

Page 39

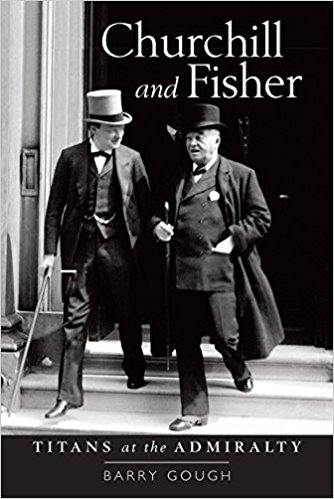

Barry Gough, Churchill and Fisher: Titans at the Admiralty, Seaforth (UK) and Naval Institute Press (US), 2017, 600 pages, £35 / $39.95. 978–1526703569

Review by Stephen McLaughlin

Stephen McLaughlin is an independent scholar who has written about both the Royal and Russian navies.

Canadian naval historian Barry Gough has written a book that is long past due—a dual biography of the two giants who presided over the Royal Navy from November 1914 to May 1915, Winston Churchill and Admiral of the Fleet Lord Fisher. While Churchill was a rising star in the Liberal party, John (“Jacky”) Fisher had been First Sea Lord—the navy’s professional head—from 1904 to 1910 and had been responsible for many reforms and innovations, the most famous of which was the introduction of the “all-big-gun” battleship HMS Dreadnought.

Churchill first met Fisher in 1907 and from the start was fascinated by the charismatic admiral. So in October 1914, when the somewhat passive First Sea Lord, Admiral Prince Louis of Battenberg, came under fire for his German origins, Churchill decided to replace him with the energetic but controversial Fisher. Gough dubs them the “daemonic duo,” and indeed it was a fraught partnership that ultimately imploded. Frustrated by the siphoning off of resources for the Dardanelles, in May 1915 Fisher abandoned his post while Churchill was in France, leaving no one at the Admiralty’s helm. Yet eventually the two reconciled sufficiently to coordinate their testimony before the Dardanelles Commission to minimize each other’s vulnerabilities.

2025 International Churchill Conference

Gough tells the complex story of these two men well, but inevitably a few mistakes creep into the text. There are the inevitable typos, my favorite being the renaming of French naval minister Delcassé to “Declassé”—one suspects that spellcheck has struck again! More serious are some errors of fact, e.g., Gough repeatedly implies that Reginald Hall, the Director of Naval Intelligence, was in charge of the code-breaking unit Room 40 throughout the war, when in fact he gained control over it only in May 1917, a year after Churchill and Fisher had left the Admiralty.

There are also some interpretations I would question. Gough disagrees with the contention of Christopher M. Bell in his recent work Churchill and the Dardanelles (see FH 178) that during the long buildup to the Dardanelles campaign Fisher failed to express clearly to Churchill his opposition to the operation. Yet Gough’s own work shows that Fisher did indeed waffl e, and he even states at one point that “Fisher had blown hot and cold, but at the outset he had concealed his reservations and then expressed great enthusiasm (which he later regretted).” All of this strongly suggests that Bell’s assessment is correct.

There is one final point I cannot let pass. In several places Gough repeats an old canard invented by Fisher’s enemies that he was a “materialist” interested only in building bigger and bigger ships. This ignores Fisher’s many other reforms. The Admiralty got it right in its letter of condolence, sent to Fisher’s son when the old admiral died:

There is no part in the multitudinous activities of modern naval service in which his influence has not been felt…. His remarkable abilities were displayed alike in the technical development of the Fleet and all its appurtenances, in the training and education of the personnel of the Royal Navy, and in the strategical disposition of the Sea Forces of the country….

It is time historians lay this particular historical ghost to rest; Fisher did much more than simply build HMS Dreadnought.

Interpretive quibbles aside, Gough’s work is based on a wide use of primary sources and is well written, providing many valuable insights. But it should be noted that it requires some knowledge of the naval policy and technology of the era to appreciate fully the complexities of the issues confronting Fisher and Churchill. With that caveat in mind, this book is highly recommended.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.