Finest Hour 178

Chartwell Memories

Oscar Nemon statue of Clementine and Winston on the grounds of Chartwell

April 3, 2018

Finest Hour 178, Fall 2018

Page 16

By Jonathan Dudley

Jonathan Dudley retired from the University of Wolverhampton after a career in education.

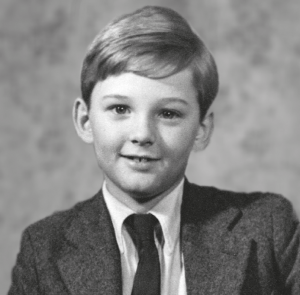

A couple of years ago, that would be in 2015, I decided to take myself back to Chartwell. I had just finished writing the first full draft of a short memoir capturing the strangeness and the wonder of staying there with Mr. and Mrs. Churchill in the summer of 1949 and again in 1950. [See p. 51.] In 1949 I was eight years old: classrooms at my all-boys school in London were furnished with double-desks, each one shared by two boys sitting side by side. The little boy I was told to sit next to in this our final year at the school could not, by any stretch of the imagination, be described as my great friend. I had hardly spoken to him during the two or three years we had been at this expensive private school in South Kensington. Nevertheless Winston, for that was his name, mentioned one day that his grandmother had asked him to bring a friend when he went to stay with her and his grandfather in their country house in Kent this summer. “Would I,” he asked me solemnly, “like to be that friend?

It was a difficult one. I was not at all sure that Winston and I had anything much in common: I loved nothing better than kicking a football around, Winston seemed little interested in sport. He seemed to enjoy making artworks of different kinds, maybe cutting out bits of paper, colouring them in, all that sort of thing and frankly, it did not interest me very much. The fact that we had not had much social contact at school seemed to me a bad omen. Perhaps he was short of friends. I did not know. But when I told my mother about the invitation, I began to sense that however forcefully I might present a case for not going it would be to no avail. “It is a great honour for the family,” my mother said, “that you should have been invited to go to Chartwell. You’re going. Let that be an end to it.”

First Visit

In the memoir I do my best to remember various incidents and episodes and the emotional dynamics that made each one memorable. Maybe I had stored these impressions away under lock and key in my memory bank for, generally speaking, these were not topics I discussed with friends or family. I was no great raconteur, and I had tended to keep my Chartwell stories to myself. I simply did not believe that I could carry my listeners with an account of mealtime rituals in the dining room or descriptions of particular dishes or observations of looks and gestures and tones of voice. No story about table decorations, or Winston’s annoying little habits, or anything else that I had observed would, I felt sure, carry enough dramatic momentum to amuse or entertain a wider audience.

2025 International Churchill Conference

Yet during my first visit in 1949 Winston and I found ourselves caught up in a number of adventures which probably did contain the elements of strong and lively narrative. When I was able to send my son, who is now forty-six, and my daughter, now forty-four, copies of the memoir, they did not hesitate to reprove me for keeping so many of the stories to myself: “you never told us about that…or that….” But there had been a private element to some of these stories. Winston and I had played as the kids we were, not always polite or tasteful kids, but wild and crazy when we were alone: Winston’s cunning plan to use an army periscope to spy on people on the groundfloor of the house; our rampage in Eddie’s bedroom. Eddie was at that time Mr. Churchill’s bodyguard, a police officer specially trained to ensure the personal security of Mr. Churchill and his family. We wanted Eddie to show us his guns and pistols, but Eddie did not want to do that. With amused forbearance, however, he allowed us to create havoc in his room for a few fun-filled minutes as we searched for weapons. When we had exhausted his patience he sent us packing. [For more about Sergeant Edmund Murray, see p. 54.]

I was surprised to find how vividly I could remember the comings and goings of various members of the Churchill family and visiting statesmen. It was fun, for instance, meeting the Churchill daughters Mary Soames and Diana Sandys, but not so much fun meeting young Winston’s father Randolph Churchill, large and hairy and stark naked in the swimming pool. It was instructive to sit next to Robert Menzies at lunch on the day when grouse was being served, and we were treated to a coup de théâtre when, on another day, a large lunch party at Chartwell was served Russian caviar, a gift to his friend Winston Churchill from none other than Joseph Stalin. Mr. Churchill took Winston and me to Chequers on the day he went to visit Prime Minister Clement Attlee. We went to Blenheim Palace, where with Mrs. Churchill and the Duchess of Marlborough looking after us, we all had tea with John (known as Albert), the 10th Duke of Marlborough, Mr. Churchill’s cousin.

Second Visit

I had enjoyed my two weeks at Chartwell in August 1949, but never expected to be invited back the following year. Mrs. Churchill was such a huge and magnetic presence, so altogether admirable and attractive in her dealings with everyone that I did have a keen sense of not wanting to let her down. Maybe I felt that I would have disappointed her, and let myself down in the process, if I had refused her invitation.

Mrs. Churchill was consistently warm and kind to me. Not warm in any physical cuddly sense—that was not her style at all. Rather she demonstrated warmth through an outpouring of real pleasure when her attention was focused upon you. She made you feel that it was both special and a delight for her to be in your company and to be talking with you. So very many of my feelings of happiness and content at Chartwell were due to the soft glitter of brilliance, which shone in her eyes and animated her personality when she was with you. This was more than mere charm—there was a diamond-like solidity behind any mere manners.

Throughout the many hours I spent in her company in the dining room at Chartwell I came to recognise some of the ways Mrs. Churchill’s family relied on her, not just for her familial love and affection and not just for her extraordinary skills—it seemed to me—as household manager. But all the members of her family that I met seemed to value, if not depend upon, the rock-solid strength of her character. Mrs. Churchill did not attempt to mask the strength of her convictions, nor the importance she attached to the values, which informed her daily life. Sometimes Mr. Churchill would appear to be uncertain whether a point he had just made in conversation was altogether acceptable or whether it betrayed a flawed or dubious moral outlook. On some of these occasions he would look across at Mrs. Churchill sitting at the other end of the long table, with a beseeching almost plaintive look that, when I think of it, still touches me. The look said first how much he loved her, and second how much he needed her thoughts and guidance on the matter in question that he did not feel altogether certain about.

I could see from his composure, his little looks and expressions how much Mr. Churchill enjoyed being at home. He would play gentle and amused when he was with Winston and me; respectful yet commanding with Randolph; and just happy and contented with Mary and with Diana. With other adults he could clearly choose—and he did choose—what role to play, what performance to give, for his thespian range was boundless. He would perform when the occasion demanded it, even for us boys. When, on our last night, he gave us his Boer War story—an escapade from which he narrowly escaped alive—it was as if he was the complete actor, the Player King in Hamlet. And I remember the house cinema showing of Pride and Prejudice where Mr. Churchill’s loud and critical commentary on the film had his fellow audience creased up with laughter. He was happy and he was very funny. He was at home.

Chartwell Redux

When I went back to Chartwell in 2015, I had more or less finished writing the memoir. I went because I was nursing the fond hope that my visit would somehow re-stimulate a living sense of what it had been like all those years ago: the smells, the sounds, the particular character of a room, maybe even the words and rhythms of actual conversations would come flooding back to me.

I am glad I made the effort to go. But Chartwell is a different place now. I understand and respect that.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.