Finest Hour 177

Books, Arts & Curiosities – Man of Many Faces

October 18, 2017

Finest Hour 177, Summer 2017

Page 55

Review by Peter Murray

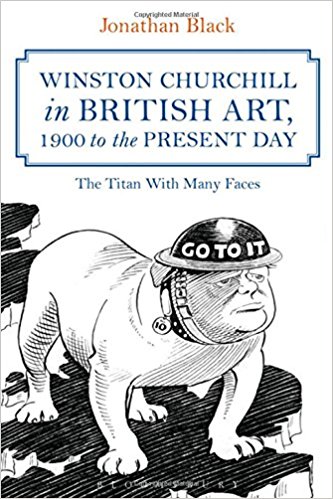

Jonathan Black, Winston Churchill in British Art, 1900 to the Present Day: The Titan with Many Faces, Bloomsbury, 2017,287 pages, £25.

ISBN 978–1472592392

Even in the twenty-first century, Winston Churchill remains a dominant figure in the political realm, a benchmark against which any budding leader of the Conservative Party must first measure up, before hurtling into the fray that is the House of Commons. But Churchill also had a sensitive side to his character. He was a keen artist, painting landscapes invested with light and colour, and forming close friendships with other artists, including Walter Sickert and Oscar Nemon. Politics, painting, and sculpture often intersected in Churchill’s life. He took lessons from the Chicago-born artist Hazel Lavery, and had his portrait painted by her husband, the hugely successful Irish artist John Lavery. Painted in 1915, Lavery’s portrait of Churchill (Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin) is one of the artist’s best works. Bleak and uncompromising, it shows a young man, full of ambition but weighed down by the responsibilities he faced as First Lord of the Admiralty—a position from which he resigned in May of that year, as a result of the disastrous Dardanelles campaign.

Lavery’s portrait is one of the first illustrations in a handsome book by Jonathan Black, Winston Churchill in British Art, 1900 to the Present Day, which documents the many representations of the British leader created both during and after his lifetime. Friendship with Hazel and John Lavery remained important to Churchill throughout the 1920’s; they played a key role in providing a communications link between the British and Irish sides during the negotiations that led to the founding of the Irish Free State—so much so that a portrait of Hazel by her husband John adorned Irish banknotes for much of the twentieth century. The 1915 Churchill portrait was followed a year later by one painted by another successful Irish artist in London, William Orpen, and commissioned by Lord Rothermere.

Churchill’s public image was largely created, and afterwards immortalised, by these portraits, paintings, and sculptures, displayed in the homes of newspaper magnates, reproduced in the popular press, and exhibited at the Royal Academy. Churchill and his wife Clementine were never slow to give their own views on these works, sometimes taking their criticism to extreme levels, as in 1954, when they secretly destroyed an official portrait by Graham Sutherland, which they loathed.

2025 International Churchill Conference

Churchill’s lively cousin, Clare Sheridan, sculpted busts of him on two occasions, in the early 1920’s, and later in 1944. Raised in Inishannon, Co. Cork, Sheridan pursued a vivid and independent life, studying art in London before travelling to Moscow in 1920, where she made portraits of the Bolshevik leaders, including Lenin and Trotsky, while taking the latter as a lover. Returning to England, Sheridan found herself out of favour with cousin Churchill and under surveillance as a possible spy, so she took herself to New York, where her Russian portraits created a sensation. She became a journalist, travelling widely and returning occasionally to England and Ireland, where she interviewed Michael Collins. Late in life, she and Churchill compared their respective lives and achievements, Churchill remarking, somewhat mournfully that while Sheridan still had her art, he had lost an Empire.

Among the other portraitists documented by Black are Ambrose McEvoy and William Nicholson, photographer Cecil Beaton, and sculptors Oscar Nemon and Ivor Roberts-Jones. Artists creating bronze memorials to Churchill had an advantage in that there was something already deeply sculptural—almost Rodinesque—about his stance and determined expression. Nemon’s bronze portrait of Churchill seated, now in the Guildhall, London, was unveiled in 1959, while a later work by the same artist, Married Love: Winston and Clementine Churchill, was unveiled in 1990 by the Queen Mother in the garden of Chartwell, country retreat of the Churchill family.

Based at Dorwich House Museum in London, and a fellow in art history at Kingston University, Jonathan Black has done an admirable job researching and writing this book. It carries on from his earlier research, funded by the British Arts and Humanities Research Council, which involved documenting First World War memorials. He went on to publish a book on the work of Ivor Roberts-Jones, who, from the 1970’s onwards, had something of a monopoly on creating memorials to wartime leaders in Whitehall. Roberts-Jones’s portrayal of Churchill was deservedly popular when unveiled in Parliament Square in 1971 and garnered further attention when given a punk grass Mohican hairdo by anti-capitalist protestors in 2000. It also featured in Danny Boyle’s documentary film shown at the opening of the 2012 Olympic Games.

Head of sculpture at Goldsmith’s College of Art until 1978, Roberts-Jones deserves a medal for maintaining his post in the face of the onslaught of the Conceptual art movement, as much as he did for his wartime service during the Burma campaign. He was awarded the 1971 Churchill commission in the face of stiff competition from Oscar Nemon. Black documents all this in detail with copious footnotes and a good index. From cartoonists to society portraitists, from émigré sculptors to Royal Academicians, artists over the years flocked to portray the heavy-jowled politician with a penetrating gaze, who helped to save the world from fascist dictatorship. This handsome book is a fitting tribute to a great leader.

Peter Murray is an art historian, writer, and curator. He lives in West Cork, Ireland.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.