Finest Hour 177

Books, Arts & Curiosities – Chronological Chaos

January 28, 2018

Finest Hour 177, Summer 2017

Page 54

Review by Lee Pollock

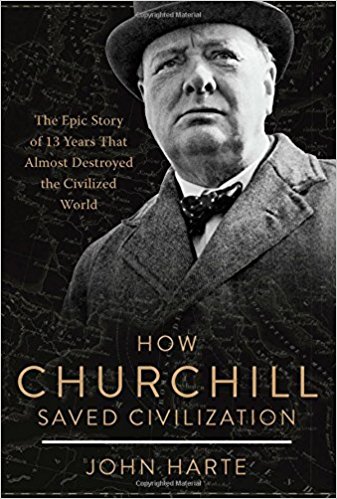

John Harte, How Churchill Saved Civilization: The Epic Story of 13 Years That Almost Destroyed the Civilized World, Skyhorse Publishing, 2017, 384 pages, $24.99. ISBN 978–1510712379

How Churchill Saved Civilization is John Harte’s first history book after a career that began as an underage RAF volunteer during the Second World War and later included stints as a journalist and playwright in the UK and South Africa and work in the advertising industry. His “Author’s Preface” sets a lofty goal explaining that the book “is intended to resolve the lingering mysteries about the circumstances that caused the Second World War and what transpired.” Harte, who now lives in Ottawa, tees up a wide range of questions such as, “How did it happen?”; “Why were the Allies unprepared?”; “What were the Nazis really up to?” and what he calls “the inevitable Jewish question.” He boldly announces, “This book was designed to answer all of them.

The effort of any first-time author should be respected, but the result in this case is mostly superficial, and the book quickly dissolves into a meandering, unfocused, and fairly prosaic account of the international history of the 1930s and 40s with an emphasis on the military campaigns of the Second World War. The title is misleading since, while Churchill appears periodically in many of the book’s twenty-eight chapters, he by no means fills the narrative. The author flits through so many subjects that the book ends up, like Churchill’s pudding, having “no theme” and failing to live up to its ambitious title.

The author’s writing can be loosely casual and awkwardly conversational. For example, speaking of the Allied invasion of Sicily, Harte notes: “It did not turn out to be the walkover that Churchill had expected.” In other cases, references sound like they are from another language, such as “historian Professor Bell” and “author Herman.”

More importantly, as Churchill noted, facts are stubborn things, and How Churchill Saved Civilization is marred by elementary, sloppy errors, which could have easily been prevented. For example, Harte describes Lord Randolph Churchill as “a former First Lord of the Admiralty in Asquith’s Liberal government.” In another chapter Harte records the demise of Benito Mussolini in April 1945 “four months after Ciano was murdered”—although the death of the dictator’s son-in-law had actually occurred in January the previous year.

Worse chronological errors follow. In the chapter on D-Day we are told, “Roosevelt was motivated… by national and self-interest, since 1945 [sic] was the year for a Presidential election.” The book refers to “the Indian mutiny of 1857–58, when Churchill was seventeen” (Churchill was born in 1874), and “civilians in Amritsar…on April 13, 1919 when Britain was at war with Germany”—five months after the Armistice!

Harte’s inability to focus his narrative is evident in his penultimate chapter, in which he includes successive, unconnected snippets on the Allied crossing of the Rhine, the discovery of Nazi concentration camps, the Yalta Conference, the dropping of the atomic bomb, and the British election of July 1945, followed by two pages on the dissolution of the British Empire and Churchill’s 1965 funeral. The chapter ends with Harte’s tip of the hat to the well-known “Rule Britannia” singalong at London’s summertime Proms concerts at Royal Albert Hall, where he imagines—perhaps correctly—that “Winston Churchill…would have loved heartily to join in the chorus.”

The book’s final chapter “Collective Guilt” is particularly eclectic, encompassing the author’s musings on “Then and Now,” including observations on Victorian and Edwardian attitudes to “sex, money, politics and religion,” followed by a lengthy review and refutation of common anti-Churchill accusations (racism, the use of poison gas, the Bengal famine, trade unions, etc.). The latter includes the entirely erroneous assertion that “Churchill had no time for trade unions.” Several more disjointed pages follow on “The Matter of Empire” and “The War Crimes Trials.”

The book’s Acknowledgments do not include the expected list of people who assisted the author’s research or read the manuscript. It seems that Harte writes pretty much in isolation, unfortunately so, since his work would have greatly benefited from input from other Churchillians. The book also includes sixteen pages of fairly ordinary and not especially clear photographs, some apparently pulled from online sources, and a number of detailed maps too small to be readable.

Harte has another book coming out this year, Churchill the Young Warrior: How He Helped Win the First World War. “Young”? Churchill was thirty-nine when the war began, and we must hope that Harte will have learned the date of the Armistice before publication.

Lee Pollock is Trustee and Adviser to the Board of the International Churchill Society and its former Executive Director.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.