Finest Hour 176

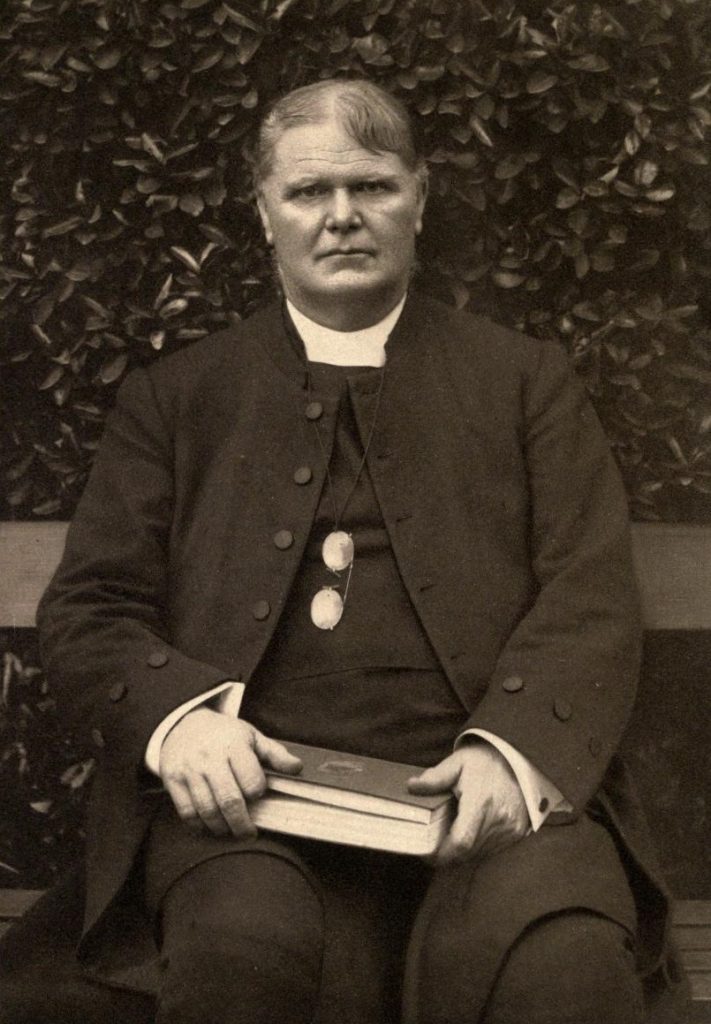

J. E. C. Welldon: Churchill’s Head Master at Harrow

September 11, 2017

Finest Hour 176, Spring 2017

Page 18

By Fred Glueckstein

In The Churchillians, Winston Churchill’s former Private Secretary Sir John Colville wrote that one of the men from his youth whom Churchill held in high regard was the Head Master of his old school, Harrow. James Edward Cowell (J. E. C.) Welldon was educated at Eton and attended King’s College, Cambridge. He was ordained as a deacon in 1883 and as a priest in 1885. In May 1883, Welldon was appointed Master of Dulwich College. He resigned this post in July 1885 to become the Head Master of Harrow, a position he held from 1885 to 1898.

After Lord Randolph decided that Winston would attend Harrow, Churchill, age thirteen, was required to take the Entrance Examination on 18 March 1888. Churchill was accompanied by Miss Charlotte Thomson, who founded and headed the preparatory school in Brighton that he attended. As explained in My Early Life, however, examinations for Churchill “were a great trial.”

Entrance Exam to Harrow

The subjects Churchill liked were history, poetry, and writing essays. He wrote, however: “The examiners were partial to Latin and mathematics. And their will prevailed. This sort of treatment had only one result: I did not do well in examinations. This was especially true of my Entrance Examination to Harrow. The Head Master, Dr. Welldon, however, took a broad-minded view of my Latin prose: he showed discernment in judging my general ability.”1

“This was the more remarkable,” wrote Churchill, “because I was found unable to answer a single question in the Latin paper. I wrote my name at the top of the page. I wrote down the number of the question ‘I’. After much reflection I put a bracket around it thus ‘(I)’. But thereafter I could not think of anything connected with it that was either relevant or true….”2

After gazing for two hours at the exam, the attendants collected Churchill’s paper and took it up to the Head Master’s table. “It was from these slender indications of scholarship that Dr. Welldon drew the conclusion that I was to pass into Harrow. It is very much to his credit. It showed that he was a man capable of looking beneath the surface of things: a man not dependent upon paper manifestations. I have always had the greatest regard for him.”3

Welldon’s decision to give Winston the opportunity to attend Harrow was severely criticized, and he was accused of favoritism. Some believed Welldon’s action was to avoid embarrassing Lord Randolph Churchill by rejecting his son. Certainly in those days the school was unlikely ever to deny admission to a grandson of a duke except in the most extraordinary cases.

Attending Harrow

Churchill entered Harrow on 17 April 1888. Although he expressed a wish to be placed into Crookshank’s House since he knew some boys there, Welldon had already agreed to take him into his own House. The Head Master, however, was unable to give the new pupil immediate admittance, so Churchill had to “wait” in one of the Small Houses run by H. O. D. Davidson. A year later, when there was room in Welldon’s House, Churchill was moved.

Latin was not Churchill’s strong subject, despite special instruction by Welldon. Clearly, Churchill’s accomplishment, in his first term, was recognition for winning the Declamation Prize for reciting, without error, 1200 lines of Macaulay’s “Lays of Ancient Rome.” Unquestionably, Welldon was delighted in young Churchill’s success.

In the official biography of his father, Randolph Churchill described the Head Master’s relationship with young Winston: “Throughout his school career Welldon showed infinite patience, and took considerable pains with Winston; ever afterwards the two retained an admiration for each other.”4

Bishop of Calcutta

After leaving Harrow in 1898, Welldon was appointed Bishop of Calcutta and Metropolitan of India. At the time of Welldon’s arrival in Calcutta, Churchill was with the army in Bangalore. Eager to see his former Head Master, he wrote to Welldon from Meerut on 22 February 1899:

I am coming to Calcutta on the 27th and am staying with the Viceroy [Lord Curzon]. I shall take the first opportunity to come and make my respects. I must offer my congratulations on the warmth of your reception. I do hope you will like India and make it the better for your stay…. I shall hope to refresh in Calcutta Cathedral the dearest memories of Harrow Chapel. I work incessantly at my book [The River War] and I propose to ask your advice on one or two matters on which I am a little in doubt.5

One of the matters on which Churchill sought Welldon’s advice was the title Lady Randolph Churchill was considering for her new quarterly journal. Churchill disliked the titles that she considered: Arena, International Quarterly, and Anglo-Saxon. Churchill had informed his mother in a letter from Meerut dated 23 February 1899: “I am going to Calcutta the day after tomorrow and shall talk to Mr. Welldon about it. There must be some classical way or some elegant English way of expressing one or other of the ideas I have suggested to you in my last.”6

Although it is not known what title Churchill’s former Head Master suggested, Lady Randolph was adamant on the name Anglo-Saxon, and she named her quarterly miscellany The Anglo-Saxon Review [see FH 174].

“…Your Star Will Rise Again…”

In 1902, due to ill health and a disagreement with the Viceroy on the subject of Christian missions, Welldon was forced to resign and return to England. After serving in Westminster until 1906, he was appointed Dean of Manchester Cathedral. In 1908, Churchill invited him to give the address at his wedding to Clementine Hozier at St. Margaret’s, Westminster, on 12 September. This Welldon did with pleasure.

Mary Soames later wrote of Welldon’s address at her parents’ wedding: “The old bishop must have been something of a prophet; in his address he said: ‘There must be in the statesman’s life many times when he depends upon the love, the insight, the penetrating sympathy and devotion of his wife. The influence which the wives of our statesmen have exercised for good upon their husbands’ lives is an unwritten chapter of English history….’”7

In the years that followed, Welldon and Churchill maintained a close association. When Churchill lost the Dundee election in 1922 and was out of office for the first time in twenty-two years, Welldon wrote him a heartfelt letter: “I do not doubt that your star will rise again, and will shine even more brightly than before.”8 Churchill’s esteem for Welldon continued until his former Head Master’s passing on 17 June 1937. Their admiration for each other covered a period of almost fifty years. Had he lived, Welldon would have been delighted and proud to see his former student become Prime Minister.

Fred Glueckstein is a frequent contributor to Finest Hour and the author of Churchill and Colonist II (2014).

Endnotes

1. Winston S. Churchill, My Early Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996), p. 15.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid., pp. 15–16.

4. Randolph S. Churchill, Winston S. Churchill, Volume I, Youth, 1874–1900 (Hillsdale: Hillsdale College Press, 2006), p. 111.

5. Autograph letter signed by Winston Churchill to Bishop J. E. C. Welldon. The Collection of Malcolm S. Forbes Jr. Provenance: F. Bartlett Watt Collection. Offered by Sotheby’s 12 December 2002, lot 15.

6. Randolph S. Churchill, Winston S. Churchill, Volume II, Young Soldier, 1896–1901 (Hillsdale: Hillsdale College Press, 2006), p. 1010.

7. Mary Soames, ed. Winston and Clementine: The Personal Letters of the Churchills (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1998), p. 17.

8. Martin Gilbert, Churchill: A Life (London: Pimlico, 2000), p. 457.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.