Finest Hour 175

The Woman He Loved: How Clementine and Winston Churchill Came to Be Married

April 19, 2017

Finest Hour 175, Winter 2017

Page 17

By Sonia Purnell

Sonia Purnell is the author of First Lady: The Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill (2015). All quotations in this article are taken from the book.

Winston Churchill was not at all the sort of husband that Lady Blanche Hozier had had in mind for her unusual daughter Clementine. He had no small talk and was not—to be frank— conventionally good-looking or athletic. He also lacked a title, a stately residence, and, above all, a suitably aristocratic pot of money. Lady Blanche came to realise, however, that despite these serious shortcomings, he was a practically perfect match.

Lady Blanche had given birth in some haste to Clementine Ogilvy Hozier on the drawing room floor of her London townhouse in Grosvenor Street on 1 April 1885 (eleven years after Churchill’s equally precocious arrival at Blenheim Palace). Clementine was her second daughter, and the grand-daughter of a Scottish earl, and was apparently blessed with the usual trappings of her blue-blooded lineage. But all was not as it seemed in the Hozier household or Clementine’s young life generally.

2024 International Churchill Conference

Lady Blanche’s anxious parents (the tenth Earl and Countess of Airlie) had married off their willful child in 1878 to one Colonel Henry Hozier—an autocrat from a brewing family, who was cold to his wife, serially unfaithful, and dead set against having children. In the absence of an obliging husband, the sexy, bored, and lonely Lady Blanche decided to shop around, reputedly entertaining up to ten lovers at a time in search of a suitable mate. One of her favourite amours, the first Lord (“Bertie”) Redesdale, most likely fathered Clementine (and possibly also her siblings Kitty, Bill, and Nellie).

That is where matters got complicated. Bertie— who was to become grandfather to the famous Mitford sisters—was married to Lady Blanche’s sister Lady Clementine, with whom he had nine other children. Thus the industrious Bertie (who was also said to have sired yet more offspring by a Japanese geisha) was probably Clementine’s father and certainly her uncle. It is likely that she was named in honour of the forbearance and generosity of her aunt Clementine.

The cuckolded Colonel Hozier, unsurprisingly, was not keen on this arrangement, and he sued Lady Blanche for divorce when Clementine was just six. She and her elder sister Kitty became helpless hostages in a bitter battle over custody and financial support. They were quickly wrested from their mother to live with Henry and his sister, the spinster Aunt Mary, who believed that children benefited greatly from being whipped.

Hozier soon tired of the responsibility, however, and so he parceled out his young charges to the care of a governess in the Hertfordshire town of Berkhamsted, just north of London. Here Clementine lived a very modest life, in which she was expected to help in the housework for hours every day and never had quite enough to eat. It was the start of a life lesson in the hardships endured by those outside the charmed circles of the landed upper classes. Her experiences at a young age—so different from the opulent splendour of Winston’s childhood at Blenheim—were to give both of them an invaluable political insight into the minds of the masses. She was not, of course, to know that at the time and just felt deeply unhappy.

Although the girls were eventually returned to their mother—after another stint in a “horrible, severe” boarding school—even then Clementine’s problems had really only just begun.

Tight Money

Lady Blanche had her young family all together, but Hozier was refusing to help financially, and money was extremely tight. Over the next eight years, the family of five moved from one set of furnished lodgings to another every few months. In part this was out of financial necessity—and the need to stay one step ahead of the creditors—but the constant roaming also suited Lady Blanche’s capricious nature.

It did not suit Clementine. By now a tearful, fearful little girl, she craved security and constancy and was granted neither. Lady Blanche continued to entertain her men-friends, and on the rare occasions when she was at home made her preference for the pretty and puckish Kitty all too obvious. Clementine, so often red-eyed with tears, was dismissed by her mother as plain, dull, and not even particularly bright. She slipped into the role of supporter and counselor to the star act Kitty; perhaps for a long time only the girls themselves realised that it was really Clementine that possessed the inner steel.

The first inkling for most came when the family moved to Dieppe in northern France to live even more cheaply and away from the moral judgements made by Lady Blanche’s compatriots of her overtly promiscuous ways. She had by now been excluded from virtually every smart salon in London and was widely considered to be “mad.” Clementine was beginning to excel at her studies (Lady Blanche was unusually progressive in viewing female education as essential, with the glaring exception of “unladylike” maths), but found it humiliating to ask for credit when she was sent out to the market for food, particularly when Lady Blanche, seen as an eccentric “milady” by the locals, was frequently losing what little money they had at the town’s casino. Clementine longed for respectability and loathed the fact that her mother was also having an affair with the artist Walter Sickert. Sickert (a man of questionable morals and recently even thought by some to be the murderous Jack the Ripper) was also carrying on with the queen of the Dieppe fish market, one Madame Villain. The two women would vent their anger at each other in plain view on the streets—with the fishwife throwing things at her rival in a jealous temper—an indignity that Clementine found difficult to bear.

Colonel Hozier Returns

Now Hozier was changing his mind about the teenaged Clementine, perceiving from afar that she was emerging as clever, graceful, and accomplished, if still apparently unnecessarily timid. He decided to visit her in Dieppe and invited her to lunch at the Hotel Royal. Lady Blanche bid her reluctant daughter to attend, although their trusty maid Justine would accompany her there and back.

Little was said between Clementine and her forbidding putative father over lunch of omelette and larksen-brochette until Hozier broke the dreaded news that he intended to take his daughter back to England with him to live with the whip-happy aunt Mary once again. Faced with this unthinkable prospect, Clementine’s shyness surrendered to a hitherto undetected determination and courage. While surreptitiously slipping on her gloves under the table, she announced calmly that her mother would refuse to allow her to leave Dieppe. The moment Justine returned, she rose from her chair and politely but firmly bade Hozier goodbye.

In a fury, Hozier suddenly barred his daughter’s way, thrusting a cold coin into Justine’s hand and pushing her violently out of the door. Clementine was now trapped and alone with this unpredictable man once more, but when he moved to fetch a cigar, she valiantly seized her chance. She flung the door open and ran full pelt towards Justine, who was waiting uncertainly outside. The two girls scrambled away as fast as they could on the icy pavements with Hozier, swearing angrily, in pursuit. Only once they neared the safety of the house where Clementine and her family were living did he finally give up on them and turn back.

The captain of the Dieppe-Newhaven steamer later confirmed that Hozier had been planning to kidnap Clementine and take her back to England that very afternoon. Her quick thinking had saved her. As her future husband Winston later put it, Lady Blanche’s once timorous daughter had displayed an exceptional ability to “rise to the level of events.” Indeed, the greater the challenge, the more impressive

Clementine became. Hardships in her early life equipped her well for her future role at her husband’s side at the centre of two world wars. Gradually she would reinvent herself as a formidable figure, no longer scared of anyone, not her father, her husband, and much later not de Gaulle, FDR, Stalin, or Hitler either. That day with her father started the process in earnest.

Runaway Bride

Her next great challenge back then, however, came soon afterwards when her beloved Kitty died suddenly from typhoid. Never had Clementine felt so alone, now fending almost entirely for herself. The family returned to England, where she was sent to a grammar school—again hardly the typical environment for an earl’s grand-daughter. Yet it was here that an inspired headmistress, Miss Beatrice Harris, finally saw the potential in Clementine. She encouraged her to be confident, self-reliant, curious about the world and great events; to champion women’s rights, including the female vote (something she would eventually convince Winston to support); to help improve the lot of the poor; and above all to stretch her mind way beyond the then normal domestic concerns of most women to politics and beyond. Clementine exulted in the respect and admiration she received at school. She thrilled in the intellectual rigour of her studies and the expectations laid at the feet of such a star pupil. She even threw herself into studying maths—albeit in secret so that her mother did not try to stop her. She laid out her textbooks on the gravestones and did her homework in a local churchyard, away from Lady Blanche’s prying eyes. Nothing would stop her achieving the highest grades.

Miss Harris knew she had university material on her hands. Few women then studied for a degree but she recognised that Clementine was special. That, however, was a step too far for Lady Blanche. For Clementine had also now emerged as a stunningly beautiful young woman, attracting admiring glances from a bevy of rich and titled men. Here now surely was a chance of financial security and the social standing that Lady Blanche had long since lost. Clementine’s sapphire eyes, slender figure and dazzling white-toothed smile would be the route for both women back into wealthy society where they rightly belonged.

All talk of university was banned. Clementine would be launched on the London circuit. Eligible suitors began to form an orderly queue. Clementine’s younger sister Nellie kept a fat file of Clementine’s offers of marriage under Rejected, Pending, and even Accepted. Indeed, Clementine was engaged three times—twice to the same man—but each time she broke it off to her own distress and to that of the gentlemen in question.

The problem was that these men were plain wrong for her—too comfortable and too compromising. They promised a life of indolence but also of stultifying restraint. One was Sidney Cornwallis Peel. The younger son of a viscount (and grandson of former Prime Minister Sir Robert), he was constant, fifteen years her senior, and rich. He took her to the theatre and sent her white violets every day. Lady Blanche thought her job was done. But Clementine knew there was more—or should be—to life. Poor Sidney was simply not exciting; his letters veered from pleading to peevish and were generally, as he conceded himself, rather dull. He offered security, money, respectability, and status. But she knew there was no passion; she was not in love. There was no intellectual spark, and without that she could not be happy. She parted from him a second and final time and began her search again.

She then agreed to marry another wealthy and older man, but again she knew he did not offer an exciting life of experience and adventure in the wider world. In short, he too was simply not clever enough. Now acquiring a reputation for inconstancy, Clementine began to think she would never marry at all.

Enter Winston

Meanwhile Winston Churchill was in hot pursuit of a wife. He was already a global celebrity—thanks to his escapades in India and Africa—and a rising political star. What he lacked in money, he more than made up for with brio, swagger, and prospects. By rights he should have made quite a catch for a woman already in possession of a fortune and he began to cast his eye round for contenders.

Churchill even devised a scheme to assess their suitability for marriage. If he judged a woman’s face to be beautiful enough to launch a thousand ships, then clearly she would qualify. If merely worthy of two hundred ships, then she might have to do, but only if absolutely necessary. If, though, her looks would justify launching, at most, a small gunboat, then clearly she would be out of the question. There was, however, a problem with this approach. It did not take into account whether these women had anything in common with him. Indeed, when he proposed to a string of “thousand ships” women they one by one turned him down, sensing the incompatibility.

They wanted luxury—he could not guarantee it; they wanted parties, balls, and gossip—he found them boring; he wanted to talk day and night about his political career—they found the subject baffling and even tedious, preferring his undivided energies to be devoted to them. If only he could find a thousand-ships woman who shared his love of affairs of state, of the cut and thrust of politics, of ideas, policies, and politicians. If only he could find a woman not just unfazed by his intellectual prowess but dazzled by it, a woman who understood his potential for greatness and would help guide him towards it, a woman whose mind was alive to the realm beyond the domestic and who was not afraid to spar with him intellectually. In short, if only he could find a woman who would be his partner not only in life but also in politics, who would use her own talents to enhance his. But did such a woman exist?

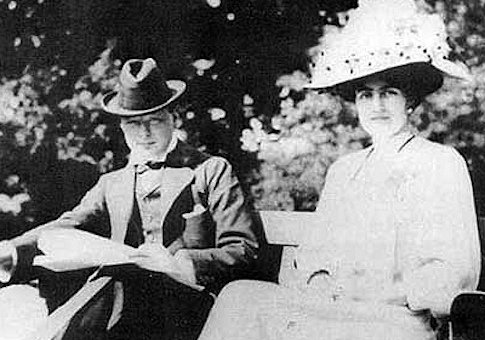

Winston and Clemmie during the Second World WarIn the spring of 1908 Winston Churchill was lingering in his bath one evening at home in Mayfair. He was grumpy about the prospect of a dinner party he fully expected to be a “bore.” His private secretary Eddie Marsh tactfully reminded him of the many kindnesses of Lady St. Helier, the grand society hostess who had invited him, and, after making more fuss, he rose from his bathwater to dress.

Winston and Clemmie during the Second World WarIn the spring of 1908 Winston Churchill was lingering in his bath one evening at home in Mayfair. He was grumpy about the prospect of a dinner party he fully expected to be a “bore.” His private secretary Eddie Marsh tactfully reminded him of the many kindnesses of Lady St. Helier, the grand society hostess who had invited him, and, after making more fuss, he rose from his bathwater to dress.

He arrived late when the other guests were already eating their main course of chicken. Amongst them was Clementine, who had been invited at the last minute to make up the numbers after another woman had fallen ill. She had been reluctant to accept, feeling tired after a day earning her living teaching French and was also worried about having nothing suitable to wear. The only spare seat at table was the one next to her, and so Churchill sat down rather grumpily at her side.

Soon, however, the pair were deep in animated conversation. They explored the current ructions and rifts in politics and the issues and characters involved. They debated the then novel ideas about establishing a proper welfare state to help the poor. They shared thoughts and observations on France, a country they both loved with a passion. They discussed history, biography, and philosophy and yet always there was more to say. Soon, the rest of the table seemed to fade away as they had only eyes and ears for each other. The other diners looked on in amazement. Churchill was ignoring all the (male) dignitaries present to talk exclusively to Miss Hozier, who looked as if she were in raptures. Much later Clementine would be asked if she thought Churchill handsome that night. She replied tactfully—but tellingly—that she had found him very “interesting.” Looks counted for little with her. Here at last was a man who led an exciting life on the public stage, one that she was excluded from on her own account because of her gender. But if she could help him perhaps she could still be a part of it too. Perhaps she too could make a difference.

Emotionally, too, there was an instant connection. Both had endured largely loveless childhoods—Winston’s mother Jennie had also often been absent and, like Lady Blanche, engaged in a life of frantic sexual intrigue at the expense of her children. Both had had cold and distant fathers. Both had become adept at hiding their consequent insecurities behind a façade—his behind apparent unfailing self-belief, hers behind a carefully maintained distance. They were both in search of comfort as well as excitement; both had endured hardships and heartache and yet were ready for great challenges in life. Six months later, they were married, and Lady Blanche was canny enough to realise that Clementine might not be destined for a rich and easy life. But she had nevertheless finally found her perfect match.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.