Finest Hour 175

Churchill’s First Great Love: Pamela Plowden

Pamela Plowden

April 21, 2017

Finest Hour 175, Winter 2017

Page 13

By Fred Glueckstein

Fred Glueckstein is the author of Churchill and Colonist II (2014) and a frequent contributor to Finest Hour.

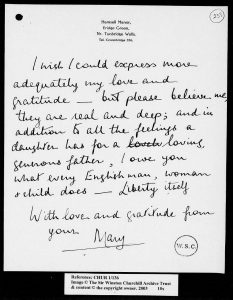

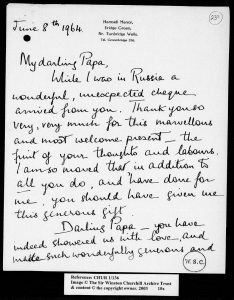

In Winston and Clementine: The Personal Letters of the Churchills (1999), Mary Soames wrote of her father: “Winston was never a ‘ladies’ man,’ yet he greatly admired beautiful, spirited women, and over these last years formed several attachments. His first great love was Pamela Plowden, daughter of the Resident at Hyderabad, whom he had met as a young subaltern in India.”1 Although he proposed marriage to her that she did not accept, Churchill’s friendship with Pamela Plowden, later Countess of Lytton, continued for the rest of his life.

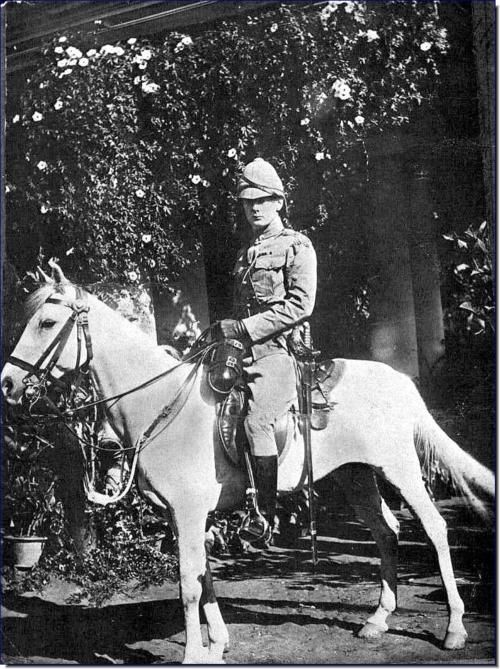

As a junior officer with the Fourth Hussars stationed in Bangalore, Churchill first met the India-born Pamela Frances Audrey Plowden in November 1896. Her father was the diplomatic representative of the British government in Hyderabad.

On 26 October 1896, Churchill wrote his mother, who knew the Plowden family, that Pamela had visited Bangalore. He told his mother that although he had the opportunity to meet Pamela for the first time, he did not, since he had not been introduced to her in England. Churchill did take the opportunity to meet her the following week, however, when he went to Secunderabad, ten miles from Hyderabad, for a polo tournament.

Captivated

On 3 November 1896, Churchill wrote his mother: “I was introduced yesterday to Miss Pamela Plowden—who lives here. I must say that she is the most beautiful girl that I have ever seen— ‘Bar none’ as the Duchess [of Marlborough] Lily says. We are going to try and do the City of Hyderabad together—on an elephant. You dare not walk or the natives spit at Europeans—which provokes retaliation leading to riots.”2

Following the successful ride through Hyderabad with Pamela, Churchill wrote his mother on 12 November 1896: “She is very beautiful and clever.”3 He also dined with the Plowdens and was in high spirits seeing Pamela, and enjoying a change of diet after eating Army food for nearly three months.

On 28 November 1898, Churchill wrote Pamela that he was leaving Egypt for India on Friday. Churchill told her that his book, The River War, “is getting on magnificently and I am quite satisfied with what is thus far completed.” And on a delicate matter she had raised in a letter to him, he wrote: “One thing I take exception to in your letter. Why do you say I am incapable of affection? Perish the thought. I love one above all others. And I shall be constant. I am no fickle gallant capriciously following the fancy of the hour. My love is deep and strong. Nothing will ever change it….”4

When Churchill finished the manuscript of The River War, he shared copies of chapters with Pamela. On 3 May 1899, he noted: “Miss P. has been vy impressed with the Proofs of the first two chapters of The River War.”5

During the Boer War in South Africa, Churchill, helping to defend an armoured train, was captured, and imprisoned. While in the States Model School prison in Pretoria, Churchill wrote Pamela on 18 November 1899:

Pamela, Not a vy satisfactory address to write from. I expect to be released as I was taken quite unarmed and with my full credentials as a correspondent. But I write you this line to tell you that among new and vivid scenes I think often of you. Yours always, Winston S. Churchill.6

After his arguments to be released as a noncombatant were rejected by the Boers, Churchill decided to escape, which he did on the evening of 12 December 1899. After British troops entered Pretoria, Churchill wrote his mother on 9 June 1900: “I propose to come home. Politics, Pamela, finances and books all need my attention.”7

GET OUR BULLETIN

Estrangement

Shortly before returning from South Africa, Lady Randolph wrote him: “Pamela is devoted to you and if yr love has grown as hers—I have no doubt it is only a question of time for you 2 to marry.”8 By October 1900, however, there was common talk in London society that Churchill had “put off” with Pamela.

What may have been closer to the truth was the explanation given by Sir John Colville, Churchill’s Private Secretary and later intimate friend. In Colville’s book The Churchillians, he wrote: “… he fell head over heels in love with Pamela Plowden. For her no trouble was too great or too time-consuming. He proposed to her in a punt on the river while they were both staying at Warwick Castle.”9 Colville wrote that she refused his marriage proposal.

In December 1900, Churchill spent Christmas in Ottawa as the guest of Lord and Lady Minto at Government House. “By good fortune or good management,” wrote Churchill’s son Randolph, “Miss Plowden was there.”10 Lord Minto later wrote Lady Churchill that in observing both Winston and Pamela: “Everything seemed to me…platonic.”11

Yet, Churchill’s feelings for Pamela were evident in a letter from Churchill to his mother from Ottawa. He wrote: “Pamela was there and apparently quite happy. We had no painful discussions, but there is no doubt in my mind that she is the only woman I could ever live happily with.”12

On 1 February 1902, The New York Times reported from London: “Miss Pamela Plowden, one of London’s most beautiful women, is now reported to be engaged to Lord Lytton. Miss Plowden frequently has been said to have been engaged, but, as The Daily Chronicle says: ‘She now makes an alliance that was well worth waiting for.’”13

Countess of Lytton

Two months later, on 3 April 1902, Pamela Plowden married the Earl of Lytton at St. Margaret’s Church, Westminster. It was reported that the wedding presents were numerous and included a diamond bird-of-paradise from the King and Queen.

The Lyttons lived in Knebworth House, a picturesque estate in Hertfordshire. They had two sons and two daughters. At the time of their marriage, Lord Lytton was a Member of Parliament.14

On 13 December 1905, Churchill was named Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies by Prime Minister Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman. Churchill asked Edward Marsh, a Colonial Office clerk, if he would be his Private Secretary. Unsure if he could work with Churchill, Marsh went to see Lady Lytton before making a decision. She told Marsh: “The first time you meet Winston, you see all his faults, and the rest of your life you spend in discovering his virtues.”15 Marsh accepted the position and faithfully served Churchill many years.

On 11 August 1908, Churchill asked Clementine Hozier to marry him, and she accepted. Before it was made public, Churchill informed his family, closest friends, Cabinet colleagues, and other important public figures of his engagement. To Pamela, he wrote: “I am to marry Clementine & I say to you as you said to me when you married Victor—you must always be our best friend.”16

In the years that followed, Pamela and Churchill remained close friends. When the Churchills’ youngest daughter Marigold died at age two in 1921, Pamela wrote on hearing the news: “What torture for a parent’s heart. I can only pray that as time passes, many precious things will come to you, to help your wound to heal.”17

Tragically, Pamela and Lord Lytton lost their son Edward, at the age of twenty-nine. Edward Lytton was killed in the crash of a Hawker Hart, a two-seater biplane light bomber at Hendon on 1 May 1933, while serving with the Auxiliary Air Force.

When Churchill became Prime Minister in 1940, Pamela was one of many friends who celebrated: “All your life I have known you would become PM, ever since the Hansom Cab days. Yet, now that you are, the news sets one’s heart beating like a sudden surprise. Your task is stupendous.” Churchill replied by telegram: “Thank you so much dear Pamela.”18

During the war, tragedy again struck Pamela and her husband when their son Alexander was killed at the Second Battle of El Alamein in October 1942. After the war, Churchill sent Pamela a copy of the yet unpublished first volume of his memoirs: “…it may amuse you,” he wrote, “to keep these galley proofs.”19

“Do let us meet again soon.”

In the postwar years, Churchill and Pamela maintained their friendship, as seen in his Engagement Calendar for January 1950. Despite feeling ill and seeing his doctor on 24 January and with the General Election forthcoming, Churchill maintained an active social calendar. The Engagement Calendar for 27 January reads: “8:00 Lady Lytton to dinner.”20

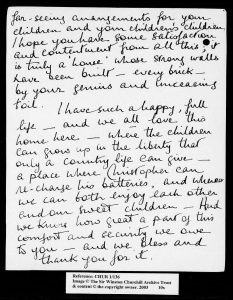

In October 1950, Lady Lytton wrote Churchill to remind him that fifty years had passed since he had proposed marriage to her. He responded in his own hand from Chartwell: “My dearest Pamela, I put yr lovely letter of October 2 on one side for me to answer above all. Alas the precaution failed. It got among other letters. I have had (as you may guess) an awful time lately– exciting, exhausting, absorbing– and it is not till now that I can tell you how much I cherish yr signal across the years, from the days when I was a freak—always that—but much hated & ruled out, but there was one who saw some qualities, & it is to you that I am most deeply grateful.”

Churchill continued: “Do let us meet again soon. The Parl. will be sitting in November & perhaps you wd. come & lunch one day. Clemmie will telephone a plan. Fifty years!—how stunning! But after all it is better than a hundred. Then there wd not be memory. With my deepest thoughts & love. From Winston”21

In March 1951 Churchill was again affected by illness and was advised to rest for a few days. He wrote Pamela and mentioned his health: “I am laid up with an unexpectedly violent reaction to a penicillin injection which I took. I had a dreadful night with pain and a swollen face.”22

In August 1951, Churchill made plans to meet Clementine in France. He wrote Pamela of his travel plans: “for I hope to paint as well as toil at the Book— Volume V now going into final print!” Churchill also referred to their courtship years ago: “I am sure you are happy at Knebworth, but the world is grim, & I am glad we had our lives when we did. I shd be vy doubtful about beginning all over again. Poor India—a hard fate lies before her. Not yr fault or mine anyhow.”23

In the spring of 1953, Churchill accepted the Queen’s request that he become a Knight of the Garter. In answer to a letter of congratulations from Pamela, he confided to his old friend: “I took it because it was the Queen’s wish. I think she is splendid.”24

In his letter, Churchill also recognized his receiving the Queen’s tribute would bring back sad memories to Pamela of her husband and son. “I am sorry that the Garter stirs poignant memories in yr mind of dear Victor [Pamela’s husband had died 25 October 1947 and had been a Knight of the Garter] and valiant Antony. You have indeed had fearful blows to bear in life. Still courage and beauty have conquered all…. With my best love, Yours devotedly W.”25

“…one of his most favoured guests.”

In the years that followed, Pamela came to lunch and spent weekends with Winston and Clementine at Chartwell. On occasion, Churchill invited guests, including Pamela, when Clementine was away. In August 1956, he wrote Clementine: “Violet [Asquith/ Bonham Carter] is coming to spend the night of Bank Holiday with me, and thereafter I have Juliet [Lady Juliet Duff]. I propose to ask Pamela for the following week.”26 When Churchill was abroad, Clementine would see Pamela at Knebworth.

John Colville described Countess of Lytton in her later years: “Gentle in manner but quick of wit, and still beautiful in her old age, she remained on affectionate terms with her former suitor and one of his most favoured guests.”27

Colville, who was close to the Churchill family, described Clementine’s feelings about Pamela: “Clementine Churchill, by no means predisposed to like or approve of her husband’s friends, whether male or female, made an enthusiastic exception in the case of Lady Lytton, whose presence was always welcomed. She did, however, admit to feeling just a touch of jealousy when she saw Winston and Pamela together, although she knew well that in her husband’s eyes no woman came within distant range of her.”28

Six years after Churchill’s passing, Pamela, Countess of Lytton died in 1971 at the age of ninety-six. Known for her beauty, charm, and cleverness, as well as a successful socialite, wife, and mother, Pamela Plowden will also be remembered as Winston Churchill’s first great love and close lifetime friend.

Endnotes

1. Mary Soames, ed., Winston and Clementine: The Personal Letters of the Churchills (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1999), p. 5.

2. Randolph S. Churchill, Winston S. Churchill, Volume I, Youth 1874–1900 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2006), p. 296.

3. Ibid., p. 425.

4. Ibid., p. 297.

5. William Manchester, The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill Visions of Glory, 1874–1932 (New York: Little Brown and Company, 1983), p. 289.

6. Winston Churchill to Pamela Plowden, 18 November 1899, Christie’s auction, 2 December 2003, Lot 49.

7. Martin Gilbert, Churchill: A Life (London: Pimlico, 2000), p. 129.

8. Randolph S. Churchill, p. 544.

9. John Colville, The Churchillians (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1981), p. 112.

10. Randolph S. Churchill, p. 544.

11. Manchester, p. 366.

12. Ibid.

13. “Miss Plowden Engaged. English Beauty, It Is Said, Is to Become Lord Lytton’s Wife,” The New York Times, 1 February 1902, p. 4.

14. “Earl of Lytton Weds Pamela Plowden,” The Washington Post, 4 April 1902, p. 7.

15. Gilbert, p. 174.

16. Randolph S. Churchill, Winston S. Churchill, Volume II, Young Statesman 1901–1914 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2007), p. 269.

17. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, Volume IV, World in Torment 1916–1922 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2006), p. 611.

18. Gilbert, Churchill: A Life, p. 645.

19. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, Volume VI, Finest Hour 1939–1941 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2011), p. 327, f. 5.

20. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, Volume VIII, Never Despair 1945–1965 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2013), pp. 414–15.

21. Ibid., p. 506.

22. Ibid., p. 562.

23. Ibid., p. 597.

24. Ibid., p. 630.

25. Ibid.

26. Ibid., p. 824.

27. Colville, p. 112.

28. Ibid.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.