Finest Hour 175

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – Time, Gentlemen, Please

April 9, 2017

Finest Hour 175, Winter 2017

Page 43

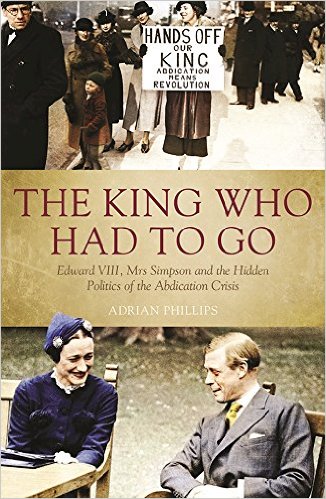

Adrian Phillips, The King Who Had to Go: Edward VIII, Mrs Simpson and the Hidden Politics of the Abdication Crisis, Biteback Publishing, 2016, 394 pages, £25.

ISBN 978–1785900259

Review by John Campbell

John Campbell’s books include major biographies of F. E. Smith, Aneurin Bevan, Edward Heath, Margaret Thatcher, and most recently Roy Jenkins.

So much has already been written about the abdication of King Edward VIII in 1936 that one wonders what more there can be to say. But Adrian Phillips has found a new angle by focussing on the role of the senior Whitehall mandarins in alerting the politicians, even before George V’s death, to the potential danger to the Crown posed by the Prince of Wales’s determination to marry an unsuitable American divorcee, and pressing them to take action to get rid of him. In this reading the key figures were Sir Warren Fisher, the powerful head of the home civil service since 1919, and Sir Horace Wilson, his protégé and eventual successor, who held a more shadowy but equally influential position as special adviser to the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin. Between them Fisher and Wilson played a crucial but hitherto under-appreciated part behind the scenes in driving the crisis to its swift conclusion.

2025 International Churchill Conference

Phillips’ insight derives largely from the discrepancy between the bland official account, which Wilson wrote for the record soon after the event, and the notes he wrote at the time, which reveal far more of the alarm, urgency, and ruthlessness of those he calls the “hardliners,” notably Neville Chamberlain, and their impatience with Baldwin’s apparent reluctance to grasp the nettle. But he has also drawn on an impressive range of other contemporary accounts and diaries, many unpublished and some quite obscure, to produce an almost hour-by-hour examination of the scheming and calculations of a wide range of players with different agendas that led to the eventual result. Paradoxically, however, all this new detail of the pressure on Baldwin to force the issue actually serves to confirm the accepted view that he played it very skilfully. By giving the King time to see that his position was impossible he was able to present his abdication to the House of Commons and the world as Edward’s own entirely voluntary and honourable choice, glossing over all the machinations, politicking, and pressures that had been brought to bear over the previous weeks.

The main interest for readers of Finest Hour, however, lies in the light shed on Churchill’s role as the King’s most prominent supporter. It is true that Winston felt a sentimental and romantic loyalty to the new King and wanted passionately to enable him to keep his throne. But he did not care about Wallis Simpson. “In the ultimate analysis of the Monarchy,” the wife of Edward’s private secretary recorded him saying at a dinner party, “she simply did not count one way or the other.” In his reverence for the monarchy, however, and his disdain for the King’s “cutie,” Churchill failed to appreciate that if forced into a corner, as he eventually was, Edward would choose to give up the throne before he would give up Wallis. So he was always backing a loser. As Lord Beaverbrook—for much less honourable reasons Edward’s other principal supporter—put it: “Our cock won’t fight.”

What Phillips vividly brings out, however, is the depth of suspicion and raw hostility that Churchill aroused at this time. “Winston is never so excited as when he [is] doing a ramp for his own private ends,” Leo Amery wrote in his diary. “Winston has thought this a wonderful opportunity of scuppering [Baldwin] by the help of Harmsworth and Beaverbrook. What a fool he is when it comes to any question of political judgement.” Senior Conservatives really believed that Churchill was trying to use the crisis to bring down the government. “The Conservatives will resign,” one Cabinet Minister raved, “and the premiership will be hawked about to anyone who will take it….Winston Churchill will summon a party meeting, create a new party and rule the country!”

Duff Cooper recorded a meeting of second-rank ministers taking this fantasy to still more lurid heights: “They thought a coup d’etat was not impossible. They suggested that the King might accept the Prime Minister’s resignation and send for Winston…. If he were defeated in the House of Commons he could go to the country….An attempt might even be made to upset the Parliamentary system altogether….Beaverbrook and Rothermere would work with Winston: so would the Fascists; so might some elements of the left.”

Churchill as a sort of British Mussolini? This was the lowest point in his whole career: when he tried to plead in the House of Commons for delay to allow the King to reach his own decision, he was shouted down with cries of “Twister.” The idea that four years later he would become the leader of a unity government fighting for the nation’s life would at that moment have seemed impossibly far-fetched.

Adrian Phillips has written an excellent book, which sheds fresh light on events with which many will think they are already familiar.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.