Finest Hour 175

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – The Noblest Roman

February 19, 2017

Finest Hour 175, Winter 2017

Page 48

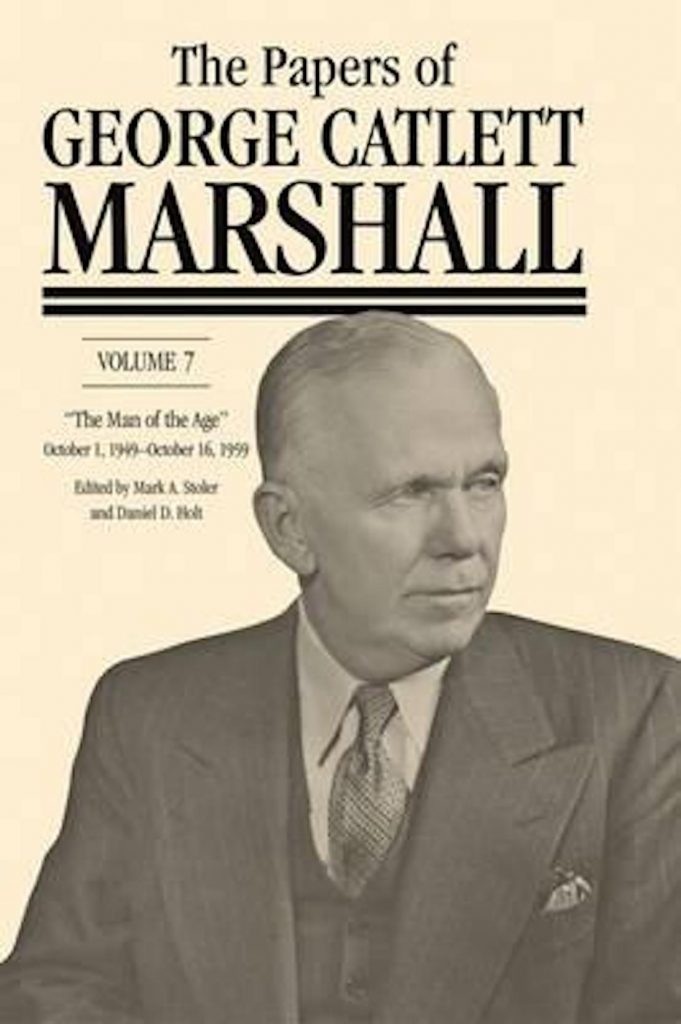

Mark A. Stoler and Daniel D. Holt, eds., The Papers of George Catlett Marshall, volume 7, “The Man of the Age,” October 1, 1949–October 16, 1959, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016, 1200 pages, $90.

ISBN 978–1421419626

Review by William I. Hitchcock

William I. Hitchcock is Professor of History at the University of Virginia.

Despite his enormous influence on the course of the twentieth century, George C. Marshall remains somewhat obscure to most Americans. His name resonates principally because of his leadership of the Marshall Plan, which sent some twelve billion dollars to Europe and spurred a revival of the economy in the aftermath of the Second World War. But Marshall’s contribution to American victory in the Second World War as Chief of Staff of the United States Army, as well as his role as Harry Truman’s Secretary of State and Secretary of Defense, deserve more acclaim.

The George C. Marshall Foundation has been working hard to secure Marshall’s place in history by editing and publishing Marshall’s personal papers. In conjunction with Johns Hopkins University Press, the Foundation has now completed a seven-volume set of Marshall’s papers that will stand for generations to come as a distinguished and fitting tribute to Marshall’s memory.

Volume 7 contains 626 documents, in addition to extensive and helpful footnotes and comments covering the last decade of Marshall’s life. In these years, October 1949 to October 1959, Marshall served as head of the American Red Cross and as chairman of the American Battle Monuments Commission, as well as Secretary of Defense in the terribly difficult first year of the Korean War. About a third of the volume contains material written by Marshall during his retirement until his death.

Marshall left the State Department in January 1949 because of ill-health, but he did not stay inactive for long. When the Korean War broke out in June 1950, Harry Truman decided to commit US forces to the defense of South Korea. The first months brought little but disaster for American and allied troops. Truman knew that he needed strong leaders to take the helm of the war effort. He fired his feckless and widely disliked Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson and drove from Washington to Marshall’s house in Leesburg, Virginia, on the Fourth of July, 1950, to ask Marshall if he would take the job. Marshall was reluctant, having already given so many years to public service in wartime. But as he wrote his goddaughter, “when the president motors down and sits under our oaks and tells me of his difficulties, he has me at a disadvantage” (146). Marshall accepted the appointment, but asked to serve for only one year in light of his failing health.

A number of Republican Senators opposed the appointment. This was the era of McCarthyism, and Senator Joe McCarthy along with a few conspiracy-minded Republicans asserted that Marshall, as special envoy to China in 1945–46, had somehow had a hand in the eventual triumph of Mao’s communist forces there. Senator William Jenner of Indiana, for example, called Marshall “a living lie” and a “conspirator” against American interests. Marshall was nonetheless confirmed and sworn in on 21 September 1950.

Marshall’s principal contribution to the war effort was to mobilize US military manpower, so recently demobilized after 1945, and get it back into fighting trim. He also lent his enormous prestige to Truman, an embattled president who did not really know how to run a war. Marshall brought with him to the Pentagon as his deputy Robert A. Lovett, one of the ablest administrators of his generation.

Marshall’s biggest challenge came in dealing with the headstrong commander of allied forces in Korea, General Douglas MacArthur, who wanted to expand the war and carry it into China against the president’s wishes. In the spring of 1951, after repeated acts of defiance from MacArthur, Truman asked his senior advisers whether he should relieve MacArthur of his command. With his strong political connections among Republicans in Congress, MacArthur could make great trouble for the president if he came home disgruntled and embittered. Marshall therefore recommended against firing MacArthur but changed his mind after consulting with other senior military commanders.

What makes this volume such a treasure trove and a pleasure to peruse is that the editors have done a brilliant job of integrating helpful commentary and explanatory notes throughout the collection. The reader is drawn deeply into the complexities of an era in which great figures made history under enormous stress and strain. In these pages, one comes to appreciate the dignity and sagacity of one of America’s greatest soldier-statesmen, the man Winston Churchill— borrowing from Shakespeare—described as “the Noblest Roman,” George C. Marshall.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.