Finest Hour 174

Winston Wept: The Extraordinary Lachrymosity and Romantic Imagination of Winston Churchill

December 18, 2016

Finest Hour 174, Autumn 2016

Page 34

By Andrew Roberts

Andrew Roberts is the author of many books, including, most recently, the major new biography Napoleon. His next book will be a full-scale biography of Churchill. This article is adapted from his speech to the 33rd International Churchill Conference in Washington, D. C., 29 October 2016

The concept of the British stiff upper lip was invented by the Victorians, and was especially prevalent in the upper classes, where it was considered infra dig to show one’s emotions openly. It was widely believed that the British Empire itself depended on the capacity of officers and gentlemen to rise above their natural human emotions and stay calm and collected, regardless of whatever appalling thing was happening. The very centre of that British belief-system was to be found in the British Army.

The concept of the British stiff upper lip was invented by the Victorians, and was especially prevalent in the upper classes, where it was considered infra dig to show one’s emotions openly. It was widely believed that the British Empire itself depended on the capacity of officers and gentlemen to rise above their natural human emotions and stay calm and collected, regardless of whatever appalling thing was happening. The very centre of that British belief-system was to be found in the British Army.

2025 International Churchill Conference

In earlier periods tearfulness did not imply a lack of manliness or self-control. At Admiral Horatio Nelson’s funeral in January 1806, for example, every single one of the eight admirals who carried the coffin down the Nave of St Paul’s Cathedral was in tears, as were at least half of the all-male congregation. Regency men were not expected to have to control their emotions in the way that their Victorian grandsons and great-grandsons were.

Yet there was one Victorian upper-class British Army officer and gentleman who cried in public to such an extraordinary extent that it was remarked upon on so many occasions that we need to regard him instead as a Regency figure born out of his time. Winston Churchill was a man of such powerful emotions, with

a profoundly romantic imagination and capacity for empathy, and also possessing such aristocratic disregard of what others thought of him, that if he felt like crying, he just did. Such was his historical imagination too that this astonishing lachrymosity could be unleashed at minor moments as well as on great occasions, especially if martial music was involved.

Churchill’s last private secretary, Sir Anthony Montague Browne, once listed some of the things that triggered tears from his boss. These included everything from tales of heroism to a noble dog struggling through the snow to his master.

When it came to blood, toil, tears and sweat, Churchill knew about them all, especially tears. So here are a few occasions, taken chronologically, in which Churchill was recorded as crying.

The Record

On 30 September 1897, after his great friend Lieutenant William Browne-Clayton was killed close to him on an expedition along India’s Northwest Frontier, Churchill wrote to his mother, “I rarely detect genuine emotion in myself,” and “I must rank it as a rare instance the fact that I cried when I saw poor Browne-Clayton literally cut to pieces on a stretcher.”1

In 1921 when his faithful manservant Thomas Walden died, who had worked for his father before him, Churchill wrote to Clementine after the funeral: “Alas my dearest I grieve to have lost this humble friend devoted and true and whom I have known since I was a youth….”2 Few other aristocrats of the day would have described his manservant as a friend.

Naturally he cried for his other friends. On the death of F. E. Smith, Lord Birkenhead, in 1930, “Last night Winston wept for his friend,” Clementine wrote to Birkenhead’s widow Margaret. “He said several times ‘I feel so lonely.’”3 “I remember how [Churchill] shed tears at T. E. Lawrence’s funeral in 1935,” wrote Captain Basil Liddell Hart.4

The day after his abdication, the former Edward VIII had lunch with Churchill on 11 December 1936 and noticed how affected his guest was: “As I saw Mr Churchill off, there were tears in his eyes. I can still see him standing at the door; his hat in one hand, stick in the other. Something must have stirred in his mind; tapping out the solemn measure with his walking stock, he began to recite, as if to himself: ‘He nothing common did or mean / Upon that memorable scene.’ His resonant voice seemed to give especial poignancy to those lines from the ode by Andrew Marvell on the beheading of Charles I.”5

The War

On 13 May 1940, three days after Churchill became Prime Minister and coincidentally the same day as his “blood, toil, tears, and sweat” speech, Harold Nicolson recorded that Lloyd George made “a moving speech telling Winston how fond he is of him. Winston cries slightly and mops his eyes.”6 Lloyd George’s private secretary A. J. Sylvester recorded how “Winston’s eyes filled with tears, he buried his head quickly in his left hand and wiped his face.”7

On 4 July 1940 Churchill cried after the House of Commons applauded his decision to sink the French fleet at Oran. “When Churchill finished his speech and sank into his seat,” recorded the Soviet ambassador Ivan Maisky, “the whole House, irrespective of party affiliation, jumped to its feet and applauded the prime minister for several minutes—a loud, powerful and unanimous ovation. Sitting on the Treasury bench, the tension draining from his body, Churchill lowered his head and the tears ran down his cheeks.” It was a strong, stirring scene. “At last we have a real leader!” was the cry echoing through the lobbies.8 Churchill’s private secretary John Colville recorded of that occasion, “Winston left the House visibly affected. I heard him say to [Leslie] Hore-Belisha ‘This is heartbreaking for me.’”9

Visiting an air-raid shelter where forty people had been killed in the East End of London after the first big raid of the Blitz on 8 September 1940, Churchill, in the words of a letter from Pug Ismay, “broke down completely” at his welcome. “You see, he really cares,” a woman called out, “he’s crying.”10 Two months later Chips Channon noted that at Neville Chamberlain’s funeral: “Winston had the decency to cry as he stood by the coffin.”11

In January 1941, Harry Hopkins recited, “Whither thou goest, I will go.” One of those present, Ambassador Gil Winant, wrote in his memoirs how “It was hard for Mr Churchill to recall this incident without being overcome with emotion.”12 The next month Lady Diana Cooper wrote to her son from Ditchley to say “We had two lovely films after dinner—one was called Escape and the other was a very light comedy called Quiet Wedding. There were also several short reels from ‘Papa’s Ministry.’ Winston managed to cry through all of them, including the comedy.”13

In April 1941 Elizabeth Nel joined the Number 10 typing team, taking dictation from the PM. “Sometimes his voice would become thick with emotion,” she recalled, “and occasionally a tear would run down his cheek.”14 The next month he cried when visiting the destroyed chamber of the House of Commons, and did not attempt to wipe away the tears. When in June 1941 Colonel Georges Groussard, Pétain’s spy chief, met Churchill in London, his account of the sufferings of Occupied France “reduced Churchill to tears.”15 Alec Cadogan, the Permanent Under Secretary at the Foreign Office, noticed the PM crying while watching That Hamilton Woman after dinner that August.

That same year on 10 August, while singing “O God Our Help in Ages Past” on USS Augusta with Franklin Roosevelt in Newfoundland, a journalist present noticed how “Churchill was affected emotionally, as I knew he would be. His handkerchief stole from his pocket.”16 That November Clement Attlee wrote to his brother Tom about the effect that the bombing of cities had upon Churchill personally. In particular he wrote of the prime minister’s “extreme sensitiveness to suffering. I remember some years ago his eyes filling up with tears when he talked of the sufferings of the Jews in Germany while I recall the tones in which looking at Blitzed houses he said ‘poor poor little homes.’ It is a side of his character not always appreciated.”17

The fact that so many people mentioned it shows how unusual it was for statesmen to cry in public. He also cried before the troops, including during the Eighth Army march past after the battle of El Alamein and again in Tripoli in February 1943 during the march-past of the 51st Division. When Admiral Cunningham took the PM to visit the submarine crews in Algiers harbour in June, Churchill made a “delightful speech” and came away with tears running down his cheeks.18

That November, during the Cairo Conference, one day after lunch with the president, Churchill asked his daughter Sarah to arrange for a car to go to the Pyramids to see if it could get close enough to take FDR there. When it was found possible to get quite close, “My father bounded into the room and said: ‘Mr President, you simply must come to see the Sphinx and the Pyramids. I’ve arranged it all.’ When FDR tried to lean forward on the arms and about to rise—only to sink back again—Churchill turned abruptly away saying,‘We’ll wait for you in the car.’” Outside in the shimmering sunshine, Sarah “saw that his eyes were bright with tears. ‘I love that man,’ he said simply.”19

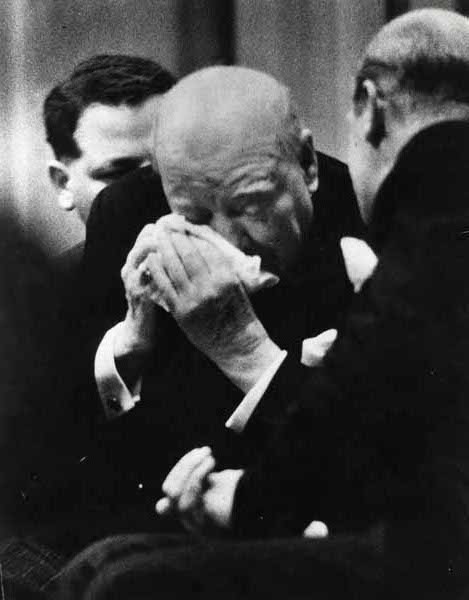

New Year 1944 saw Churchill in Marrakesh, seriously ill with pneumonia. On 18 January, he made an unexpected return to the House of Commons. “He was flushed with pleasure and emotion,” recorded the MP and diarist Harold Nicolson, “and hardly had he sat down when two large tears began to trickle down his cheeks. He mopped at them clumsily with a huge white handkerchief.”20

Naturally Churchill cried in April 1945 at FDR’s memorial service in St. Paul’s, and also when he visited FDR’s grave after the war. Three months later, the Prime Minister’s secretaries, Patrick Kinna and Elizabeth Layton, sat crying with him when the results of the 1945 election came through.

Post War

When on returning to office in 1951 Churchill learnt that the Canadian government had decided that “Rule, Britannia!” should no longer be played by the Royal Canadian Air Force or Navy, he had his defence minister Lord Ismay complain to the Canadian prime minister, Mr. St. Laurent. He almost decided that he would cancel his visit to Ottawa in January 1952 over the matter. He was persuaded not to by Clementine, and when he disembarked from the sleeper in Ottawa at the station opposite the Chateau Laurier the RCAF band struck up “Rule, Britannia!” and Churchill wept. From then on, in Colville’s words, “nobody ever dared to utter even the mildest criticism of Mr. St Laurent or of Canada.”21

The death of King George VI had the effect you would by now have expected. “When I went to the Prime Minister’s bedroom he was sitting alone with tears in his eyes,” wrote Colville, “looking straight in front of him and reading neither his official papers nor his newspapers. I had not realised how much the King had meant to him. I tried to cheer him up by saying how well he would get on with the new Queen, but all he could say was that he did not know her and she was only a child.”22 He nonetheless went down to Heathrow to meet the new Queen, and took his secretary Jane Portal to whom he was dictating in the car; she recalled “He was in a flood of tears.”23 Portal’s son Justin Welby, the present Archbishop of Canterbury, remembers seeing Churchill in tears when visiting Number 10 as a boy.

In January 1958 Churchill rang Ava Waverley to console her on the death of her second husband, John Anderson, and ended by shedding tears when discussing her first husband Ralph Wigram. That August, Brendan Bracken died of oesophagal cancer. Upon hearing the news, Churchill wept, saying “poor, dear Brendan.”24

Moral Courage

In that letter about the death of his brother officer Browne-Clayton in 1897, Churchill had told his mother “I think a keen sense of necessity or of burning wrong or injustice would make me sincere, but I rarely detect genuine emotion in myself.” All too often, this has been taken at face value, but I believe that we can now safely discard it. In fact if anything the opposite was true. Plenty of people cry at weddings and funerals. Churchill cried not only at those but also at resignations, appointments, movies (even comedies), the Blitz, great parliamentary occasions, the Holocaust, military parades and march-pasts, and old songs.

Churchill had the moral courage necessary to cry when all around his my contemporaries were keeping stiff upper lips. He was if anything a slave to his emotions, and these emotions were fine and honourable ones. The decision to fight on against the Germans in 1940 was primarily an emotional rather than a rational one, so we can all be thankful that Winston Churchill wore his heart on his sleeve in the truly extraordinary way that he did.

Endnotes

1. Con Coughlin, Churchill’s First War (London: Thomas Dunne, 2014), p. xiv.

2. Mary Soames, ed., Speaking for Themselves: The Personal Letters of Winston and Clementine Churchill (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1999), p. 240.

3. Clive Ponting, Churchill (London: Sinclair Stevenson, 1994), p. 79.

4. B. H. Liddell Hart in A. J. P. Taylor, ed., Churchill: Four Faces and the Man (London: Allen Lane, 1969), p. 197.

5. H.R.H. The Duke of Windsor, A King’s Story (London: Cassell, 1951), p. 351.

6. Harold Nicolson, The War Years (New York: Atheneum, 1967), p. 85.

7. Richard Toye, Churchill and Lloyd George (London: Macmillan, 2007), p. 355.

8. Gabriel Gorodetsky, ed., Maisky Diaries (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015), p. 290.

9. John Colville, The Fringes of Power (New York: Norton, 1985), p. 185.

10. Martin Gilbert, Churchill: A Life (New York: Henry Holt, 1991), p. 675.

11. Robert Rhodes James, ed., Chips: The Diary of Sir Henry Channon (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1967), p. 267.

12. John Gil Winant, A Letter from Grosvenor Square (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1947), pp. 29–30.

13. John Julius Norwich, ed., Darling Monster: The Letters of Lady Diana Cooper to Her Son (London: Chatto & Windus, 2013), p. 237.

14. Elizabeth Nel, Mr Churchill’s Secretary (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1958), p. 36.

15. BBC History Magazine, May 2002, p. 7.

16. H. V. Morton, Atlantic Meeting (London, Methuen, 1943), p. 101.

17. Attlee Papers, Bodleian Library, Oxford.

18. A. B. Cunningham, A Sailor’s Odyssey (London: Hutchinson, 1952), p. 543.

19. Sarah Churchill, A Thread in the Tapestry (New York: Dodd, Mead and Co., 1967), pp. 62–63.

20. Harold Nicolson, pp. 344–45.

21. David Dilks, “‘The Solitary Pilgrimage’: Churchill and the Russians 1951–55,” speech to the Churchill Society for the Advancement of Parliamentary Democracy, November 1999.

22. Colville, p. 640.

23. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, Volume VIII, Never Despair, 1945–65 (London: Heineman, 1988), p. 697.

24. Charles Lysaght, Brendan Bracken (London: Allen Lane, 1979), p. 340.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.