Finest Hour 174

Churchill: Adviser and Contributor to Lady Randolph’s Quarterly Miscellany – The Anglo-Saxon Review

December 18, 2016

Finest Hour 174, Autumn 2016

Page 26

By Fred Glueckstein

Fred Glueckstein is the author of Churchill and Colonist II (2015).

Lady Randolph Churchill loved the literary world. She particularly enjoyed meeting American authors who visited England and often spoke with delight a story of her friend Mark Twain.

2025 International Churchill Conference

Lady Randolph told of a London gathering where Twain asked Mrs. J. Comyns-Carr, “You are an American, aren’t you?” Mrs. Carr explained that she was of English stock and had been brought up in Italy. “Ah, that’s it,” answered Twain. “It’s your complexity of background that makes you seem American. We are rather a mixture, of course. But I can pay you no higher compliment than to mistake you for a countryman of mine.”1 While American-born Lady Randolph found Twain’s comments extremely amusing, it is doubtful that Mrs. Comyns-Carr did.

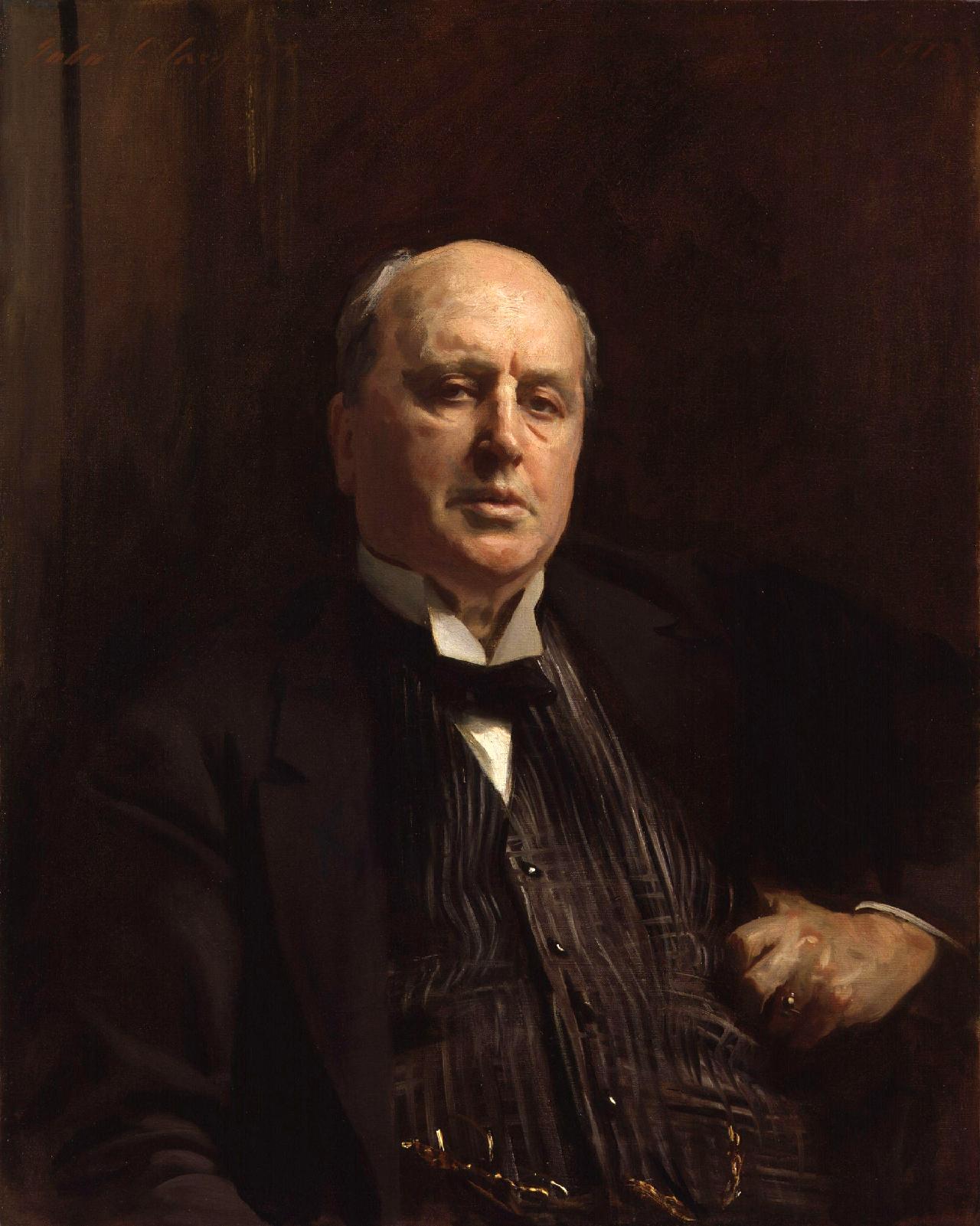

Other social events often brought Lady Randolph into contact with writers. When Stephen Crane and his wife rented Brede Place, a feudal home in Sussex built in 1350, Lady Randolph and her sisters attended a three-day party that Crane gave for sixty guests, which included Henry James, Joseph Conrad, H. Rider Haggard, and H. G. Wells.

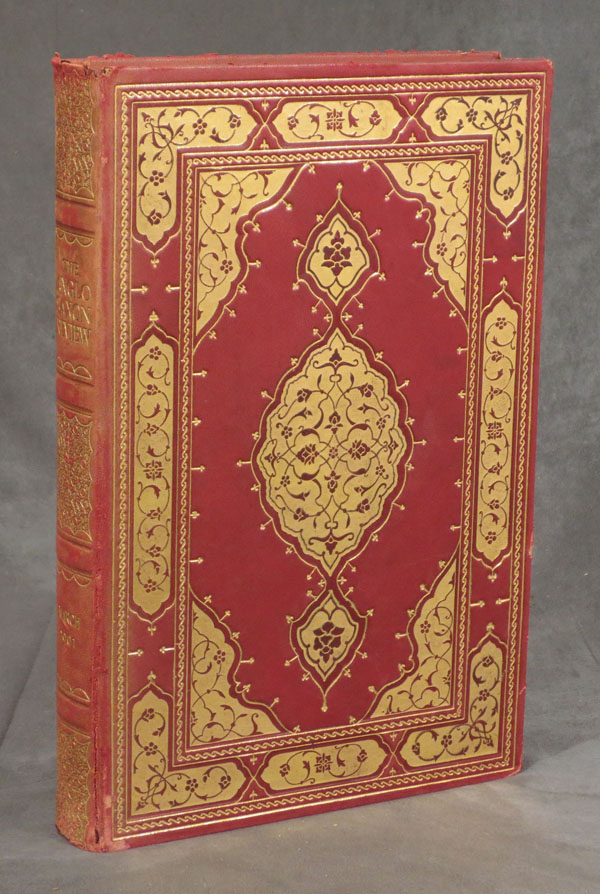

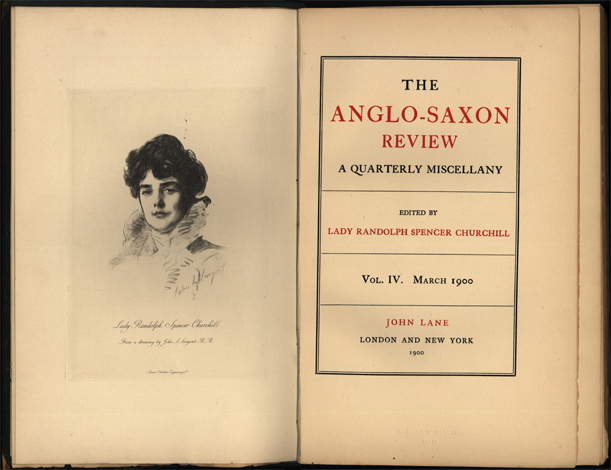

Lady Randolph’s esteem of literature and writers inspired her in late 1898 to conceive the idea of starting a literary magazine. She envisioned a quarterly miscellany edited by herself that contained articles of verse, fiction, and essays by contributors considered to be among the finest writers on both sides of the Atlantic. Each issue was to be individually decorated in a stylish pattern of gilt tooling on leather covers.

Lady Randolph foresaw the magazine as one of such literary excellence that it would be read with interest and pleasure by educated people. It would be a luxurious-looking magazine with significant writing and would be bought by the upper class through subscription and kept in their library.

It Is Founded

Lady Randolph’s son Winston was extremely enthusiastic about his mother’s idea. Back in India with the Army, he wrote her from Bangalore on 1 January 1899: “You will have an occupation and an interest in life which will make up for silly social amusements you will cease to shine in as time goes on and which will give you in the latter part of your life as fine a position in the world of taste & thought as formerly, & now in that of elegance & beauty. It is wise & philosophical. It may also be profitable. If you make £1000 a year out of it, I think that would be a lift in the dark clouds….”2

Churchill was concerned, however, about his mother’s decision to charge a guinea per copy. “If you publish at a guinea (approximately six dollars in the United States) you must give people a guinea’s worth,” he said. “I don’t think it would be possible or fair to make more profit than 2/6 a number after everything was paid, otherwise your magazine would be supported only by charity, would run for a couple of numbers and then perish. It must hold its own by its own intrinsic value & excellence. Not by the favour of friends good enough to subscribe ‘Its only a fiver, my dear,’” said Churchill.3

Understanding his mother was determined to move ahead, Churchill helped her in making the initial contacts with publishers. He also offered much advice as to the style and format.

When Lady Randolph needed a name for her literary magazine, she asked friends for suggestions. Winston advised her: “I beg you not to be in a hurry; a bad name will damn any magazine.” He went on to say that she should search for a title that would be “exquisite, rich, stately…something classical and opulent.”4

Among the names suggested to Lady Randolph were International Quarterly and Arena. One of Lady Randolph’s former lovers, Sir Edgar Vincent, suggested Anglo-Saxon, and she was captivated by the name.

Winston did not like any of the names suggested to his mother, and the title he liked least was The Anglo-Saxon. “It means nothing & has not the slightest relation to the ideas and purposes of the magazine,”5 he told Jennie on 16 February 1899.

A week later, Churchill again told his mother that he did not like the title The Anglo-Saxon: “Most unsuitable, it might do for a vy popular periodical meant to appeal to great masses on either side of the Atlantic. It is very inappropriate to a Magazine de Luxe, meant only for the cultivated few and with a distinct suspicion [of] cosmopolitanism about it.” Churchill suggested the title The Imperial Magazine, which “is less open to objection than the Anglo-Saxon, and is a sort of idea of excellence about it.”6

While travelling to Calcutta to consult with his former Head Master at Harrow, The Rev. J. E. C. Welldon, now Bishop of Calcutta and Metropolitan of India, on the title of his mother’s journal, Churchill received more shocking news from her. Lady Randolph had now added a motto to the title: Blood is thicker than water. Churchill was horrified. From Calcutta, on 2 March 1899, Churchill wrote his mother an unflattering note on the subject:

I must now turn to the Magazine. I am vy glad that you will not publish until June. I repeat all I wrote a fortnight ago about there being no hurry. But I think you have quite lost the original idea of a magazine de luxe. Your title The Anglo-Saxon with its motto Blood is thicker than water only needs the Union Jack & the Star Spangled Banner crossed on the cover to be suited to one of Harmsworth’s cheap Imperialist productions….As for the motto Blood is thicker than water I thought that that had long ago been relegated to the pothouse Music Hall.7

Although Lady Randolph decided not to use the motto, she was firm on the title. When she learned, however, that someone else had registered the same title, Lady Randolph had a simple answer; she added the word “Review” and so used The Anglo-Saxon Review.

“It is…a go.”

With the literary quarterly now named, Churchill agreed to stop complaining about the title. After he returned home from the Army, Lady Randolph put him to work on the Review. Both worked on the introduction. It was the first literary collaboration of mother and son.

The preface, attributed to Lady Randolph, had Churchill’s literary style. It read in part: “…It is with such hopes that I send the first volume out into the world—an adventurous pioneer. Yet he bears a name which may sustain him even in the hardest of struggles, and of which he will at all times endeavour to be worthy—a name under which just laws, high purpose, civilizing influence, and a fine language have been spread to the remotest regions.”8

In June 1899, Volume I of Lady Randolph Churchill’s The Anglo-Saxon Review: A Quarterly Miscellany was published in London by John L. Lane. The miscellany included the work of the following American and British writers: Henry James, Cyril Davenport, Elizabeth Robins, Whitelaw Reid, Honorable Mrs. Boyle, the Earl of Rosebery, John Oliver Hobbes, Gilbert Parker, Algernon Swinburne, Prof. Oliver Lodge, Sir Rudolf Slatkin, and Frank Swetlenham.

London reviewers were divided on the literary merits of the new journal. The Daily Chronicle said: “Notwithstanding the gorgeous binding, it is nothing but a colorable imitation of The Yellow Book [a quarterly literary periodical priced at 5s. published in London from 1894 to 1897] with the same writers, the same makeup, and the same kind of contests.” The Times wrote: “Lady Randolph has planned her quarterly with daring and originality and has carried it out with remarkable success.”9

London reviewers were divided on the literary merits of the new journal. The Daily Chronicle said: “Notwithstanding the gorgeous binding, it is nothing but a colorable imitation of The Yellow Book [a quarterly literary periodical priced at 5s. published in London from 1894 to 1897] with the same writers, the same makeup, and the same kind of contests.” The Times wrote: “Lady Randolph has planned her quarterly with daring and originality and has carried it out with remarkable success.”9

Across the Atlantic, The New York Times praised The Anglo-Saxon Review. The reviewer said in part: “And whoever has seen it has to own that it justifies by its appearance the ‘swagger’ announced in its price. It is a piece of bibliophily for which one can imagine collectors ten years from now violently competing with each other. A guinea a number in London, or six dollars in New York, must seem a trifle ‘steep’ for a magazine. But mechanically, this magazine seems to justify its price. It is an extremely good piece of bookmaking…quite unique.” The reviewer acknowledged the well-known literary contributors and ended by saying, “It is, artistically and on its own merits, a go.”10

It Is Finished

Future issues of The Anglo-Saxon Review included articles by American writers such as Stephen Crane, members of England’s nobility, officers of the Church of England, members of parliament, royalty, and foreign dignitaries. Interestingly, Volume VIII, published in March 1899, contained articles by both mother and son.

Lady Randolph’s article, “Decorative Domestic Art,” discussed the “remarkable” improvement in the furnishing and decorating of English houses during the previous twenty-five years—an improvement, she wrote, “would be difficult to find a parallel in the realm of art.”

Churchill’s article “British Cavalry” rebutted criticism of the cavalry during the fifteen months of mounted conflict in the Boer War. During that time, criticism had increased as the public learned of the losses of the Highland Brigade at Magersfontein, of the Dublin Fusiliers at Colenso, and the Inniskilling Fusiliers in the battle of Pieters.

As with the first issue, subsequent editions of The Anglo-Saxon Review were individually decorated in a detailed pattern of gilt decorative work on a leather cover. The subscription list included heads of state, royalty, and some of the wealthiest families in Britain and the United States. Each issue also contained beautiful portraits of famous people such as George Washington and Queen Victoria.

As with the first issue, subsequent editions of The Anglo-Saxon Review were individually decorated in a detailed pattern of gilt decorative work on a leather cover. The subscription list included heads of state, royalty, and some of the wealthiest families in Britain and the United States. Each issue also contained beautiful portraits of famous people such as George Washington and Queen Victoria.

Eventually, the publishing costs, high price of the magazine, and less-than-anticipated subscriptions affected the quarterly’s success, and Lady Randolph’s journal had a short life. Only ten volumes were published from June 1899 to September 1901.

Despite The Anglo-Saxon Review’s lack of ultimate success, Lady Randolph’s bold effort as editor and head of a quarterly miscellany must be applauded. Her vision, hard work, and dealings with the literary notables of America and England were a novelty for a woman. Churchill’s support and commitment to his mother’s dream were admirable, despite it being a challenging business endeavor from the onset. Lady Randolph and Winston working together on the quarterly miscellany was a splendid collaboration, one remembered in the annals of the Churchill family.

Endnotes

1. Ralph G. Martin, The Life of Lady Randolph Churchill, Vol. II The Dramatic Years, 1895–1921 (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1971), p. 265.

2. Randolph S. Churchill, Winston S. Churchill, Vol. I, Youth 1874–1900 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2006), p. 432.

3. Ibid., p. 434.

4. Martin, pp. 162–63.

5. Churchill, p. 434.

6. Ibid., p. 433.

7. Martin, p. 173.

8. “The Anglo-Saxon Review: London Reviewers Are Divided as to Its Literary Merits,” The New York Times, 2 July 1899, p. 17.

9. “The Anglo-Saxon Review,” The New York Times, 12 July 1899, p. 6.

10. Ibid.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.