Finest Hour 174

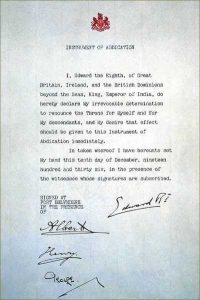

“A Vulgar Yankee Impresario” – Churchill, Major Pond, and the Lecture Tour of 1900–1901

December 12, 2016

Finest Hour 174, Autumn 2016

Page 10

By Bradley Tolppanen

Bradley Tolppanen is the author of Churchill in North America 1929 (2014).

After disembarking at New York on 8 December 1900 after a six-day voyage from Liverpool, Winston Churchill was met by Major J. B. Pond, America’s leading lecture agent. He had come to North America at Pond’s invitation to undertake a lecture tour that would eventually encompass at least thirty-seven lectures in thirty-one cities. Unlike Churchill’s first visit to America five years before, this trip was about earning money, as Churchill wrote a friend, “I pursue profit not pleasure in the States this time.”1

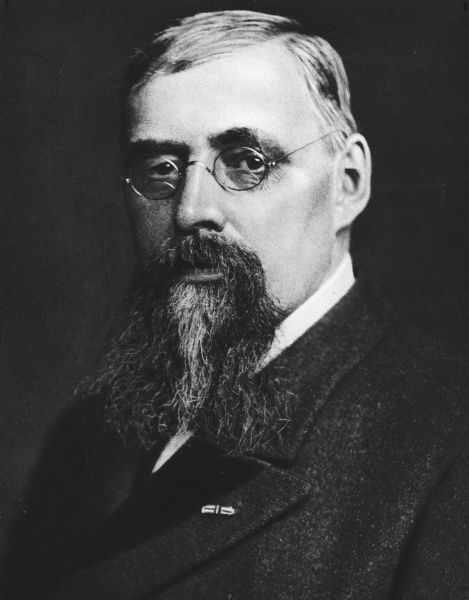

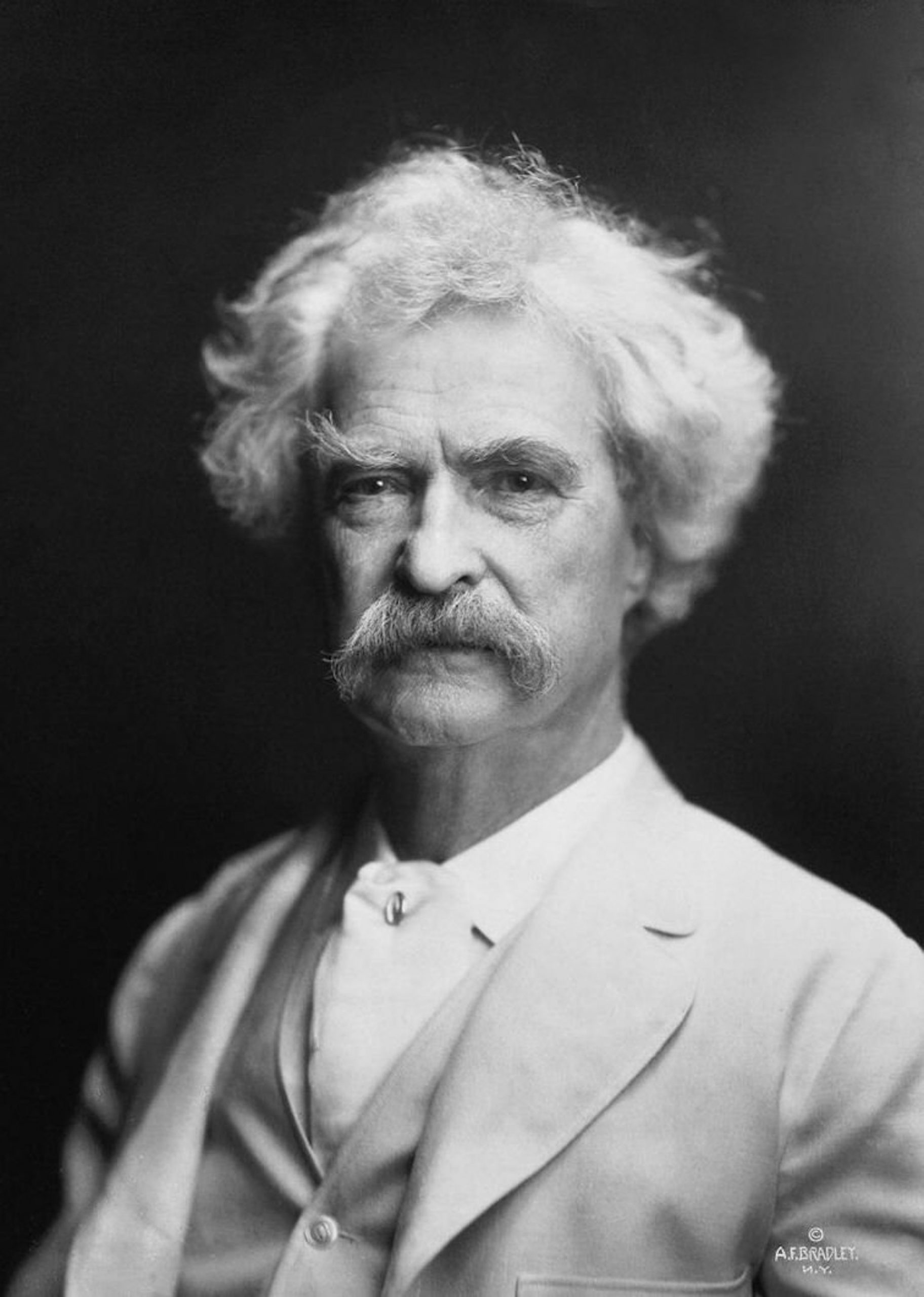

At twenty-six Churchill had high expectations for the lecture tour. After garnering £3,700 the previous month for lecturing in Britain, he arrived in New York with a £1,000 guarantee and the hope for as much as £5,000. Churchill was encouraged in his expectations by James Burton Pond, who in his career as a lecture agent had done much to “revolutionize” the field of booking prominent figures for speaking engagements. He had managed “all the famous speakers in the country,” including Mark Twain. While he liked Pond, Twain also observed that he was “neither truthful nor sensible.”2

After receiving a letter from Pond in March 1900 while he was still with the army in South Africa, Churchill followed up with the agent that summer after he was back in London. They exchanged letters confirming the date and length of the tour as well as the material for the lectures. Titled “The War as I Saw It,” Churchill’s lecture narrated his capture and escape from the Boers, the relief

of Ladysmith, and his entry into Pretoria. As the tour was arranged, he did not receive, despite his requests, a contract from Pond for his lawyers to review.

Greetings from Mark Twain

On the afternoon of Churchill’s arrival, Pond had him meet the city’s newspaper reporters at his office, with Mark Twain asking the questions. The other promotional efforts devised by Pond quickly proved an embarrassment to Churchill, who thought them “vulgar.” He was advertised as “the hero of five wars,” “author of six books,” and “future Prime Minister of England,” when in fact he had served in four wars, had written five books, and had not yet even taken his seat in the House of Commons. Worse still was that Pond had created a reception committee of prominent citizens for the New York lecture without bothering to ask most of them if they wished to serve.

The first lecture of the tour took place before a large audience in Philadelphia on 11 December. Although the crowd gave him a long burst of applause as he closed, Churchill was surprised at this first outing by the pro-Boer sympathies of some of the audience. These sympathies would be prevalent at most of his American lectures. While the lecture would always remain the same, Churchill conceded that he would “sing in a different key” depending on the mood of the audience. In Canada he was more patriotic, while with skeptical American audiences he took a less bold line.3

The first lecture of the tour took place before a large audience in Philadelphia on 11 December. Although the crowd gave him a long burst of applause as he closed, Churchill was surprised at this first outing by the pro-Boer sympathies of some of the audience. These sympathies would be prevalent at most of his American lectures. While the lecture would always remain the same, Churchill conceded that he would “sing in a different key” depending on the mood of the audience. In Canada he was more patriotic, while with skeptical American audiences he took a less bold line.3

The Philadelphia lecture brought in the fixed sum of $900. During the tour Pond either hired the theatres himself or sold the lecture to a local organization for a fixed sum, which thus avoided the necessary advance work and removed the danger of a financial loss if the lecture was poorly attended. In Canada, Pond sold all the lectures to local agents. As the tour progressed, selling the lectures for a fixed sum caused Churchill great annoyance as he, according to Pond, “preferred to speculate and take all the risk.”4

The following night Churchill lectured at the Waldorf Astoria in New York. With a “fashionable” audience occupying every seat, Pond declared it “one of the most brilliant affairs I have ever managed.” Twain presided and introduced Churchill. The expenses were quite large for the lecture, but Pond claimed a profit of $1,150.35, of which Churchill received $766.90.5

GET OUR BULLETIN

Accompanied by Pond, Churchill next lectured at New Haven on 13 December. Churchill was displeased that the appearance had been sold to a local organization for $300 and assured Pond that his only concern on the tour was financial. The following afternoon he spoke in Washington to an audience that included the British ambassador. While praising the lecture, a reporter observed that Churchill spoke in a “jerky, hesitating way,” which can be attributed to his being ill with a temperature of 102 degrees. The illness also probably contributed to problems with Pond, who thought the Englishman, unhappy with the Washington appearance, was “disagreeable and ugly.”6

Deteriorating Situation

Issues between the lecturer and agent worsened the next day in Baltimore, as Churchill spoke before a crowd of only a few hundred in a venue that seated 5,000. Churchill was finding out that, contrary to what he had been told by Pond, there was not the same interest in the tour as there had been in England. He gave Pond a talking to off-stage. Churchill told the agent that he would not continue with the tour, but Pond reassured him that the next lecture in Boston would be a success. The lecture had been sold for $500 and the local organizers would work hard to recoup their investment. While Churchill was growing disenchanted with Pond, the American had his own issues with his lecturer. According to Pond, among the expenses he had to cover was the pint of champagne Churchill drank with every breakfast.

Churchill and Pond arrived in Boston on 16 December and checked into the Hotel Touraine. That day Pond brought Winston Churchill, the American novelist, to the hotel to meet the British Winston Churchill. The meeting of the two Winston Churchills received a great deal of press attention, which can be attributed to Pond’s taking advantage of every promotional opportunity. The Boston lecture at the Tremont Temple that evening was, as Pond predicted, a financial success. As it had been sold for a fixed sum, however, Pond smirked that “it broke Mr. Churchill’s heart that some others were to reap the profits.”7

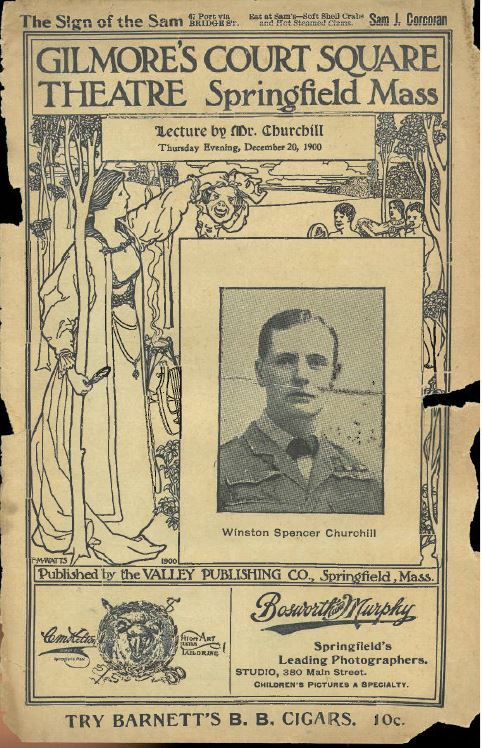

After lecturing in New Bedford on 18 December, Churchill spoke next in Hartford and then in Springfield. At the last two locales, Pond had booked the theatres himself. It was, however, the week before Christmas, a time when provincial theatres were usually closed. At Hartford, Churchill received just £10, while at Springfield a profit of a little over $200 was achieved. The Englishman was learning the hard way the truth of Twain’s remark that “if you get half as much as Pond prophesied, be content & praise God—it has not happened to another.” A disappointed Churchill wished to leave immediately to spend Christmas in Ottawa, but was dissuaded by the argument that it would be an “acknowledgement that the tour was a failure.”8

After Springfield, Pond went home for Christmas, while Churchill went to Fall River, Massachusetts, for an appearance on 21 December. It was the oddest of the tour. Churchill had been booked to speak at a private party at the home of a local industrialist, John S. Brayton. Despite his misgivings that he had been hired out like a “conjuror,” Churchill nonetheless was “charming.” He was paid £40.9

O Canada!

Churchill travelled to Ottawa, where he spent several days over Christmas as the guest of Lord and Lady Minto, the governor-general and his wife. On his arrival, he was perhaps distracted from his problems with Pond by finding that another guest was Pamela Plowden, with whom he had had a romance that was by then fading. Churchill later wrote his mother that there had been “no painful discussions” with Plowden.10

There were, however, painful discussions on 26 December between Pond and Churchill in Montreal, where the Englishman lectured at a sold-out Windsor Hall. While the lecture was entertaining, Churchill was furious with Pond, who had rejoined him in the city. Since every ticket had been sold for the lecture, Churchill thought that by selling it for a fixed sum Pond had thrown money away. It had been foolishness, in Churchill’s opinion, to have sold the Canadian dates for a fixed rate no matter the box office. These were some of the best towns on the tour, and it was costing him money.

Pond claims he was berated both before the lecture and again after it was over. The Englishman said the financial arrangements were “unfair and inequitable” and that he was being “exploited” for the benefit of Pond, his agents, and his friends. He had received $300 for Montreal, with the remaining “$900 being swallowed up by others.” The next day in Ottawa, Churchill again expressed annoyance about the local agents taking an extra share of the profits at his expense. He declared that he would not lecture beyond the Canadian capital unless a fair share of the profits was arranged, which he insisted was a 55% guarantee of all receipts. Against this background, Churchill lectured that evening to a full house at the Russell Theatre. As the lecture ended, Pond had an assistant hand Churchill a note urging him to fulfill his Canadian dates and go to Brantford, where he was next scheduled to lecture. After reading the note, Churchill told Pond, “I won’t go. There’s nothing in it for me. Look at this great audience and I only get $300 out of it.”11

Pond claims he was berated both before the lecture and again after it was over. The Englishman said the financial arrangements were “unfair and inequitable” and that he was being “exploited” for the benefit of Pond, his agents, and his friends. He had received $300 for Montreal, with the remaining “$900 being swallowed up by others.” The next day in Ottawa, Churchill again expressed annoyance about the local agents taking an extra share of the profits at his expense. He declared that he would not lecture beyond the Canadian capital unless a fair share of the profits was arranged, which he insisted was a 55% guarantee of all receipts. Against this background, Churchill lectured that evening to a full house at the Russell Theatre. As the lecture ended, Pond had an assistant hand Churchill a note urging him to fulfill his Canadian dates and go to Brantford, where he was next scheduled to lecture. After reading the note, Churchill told Pond, “I won’t go. There’s nothing in it for me. Look at this great audience and I only get $300 out of it.”11

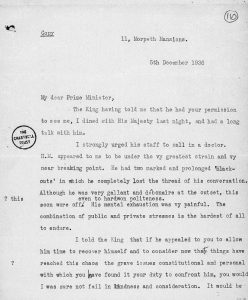

At an impasse, Churchill remained in Ottawa, and Pond left for Toronto, where he met the Canadian subagent William Houston on the morning of 28 December. With their speaker on strike in Ottawa, they agreed that the sold-out appearance in Brantford was lost. Houston then cabled Churchill that he held a contract signed by Pond as his representative for a series of Canadian lectures, including Toronto the next evening, and threatened “heavy damages if that contract is not fulfilled.” Pond probably gave an interview to the newspapers that day saying that Churchill had demanded half the proceedings from the $1300 house in Montreal, even though he had an agreement calling for a fixed sum of $250 for each lecture. He warned that the Englishman “must keep to his contract or take the consequences.” While he thought Pond’s press remarks were “very mendacious,” Churchill gave out his own statement that day in Ottawa that was not, perhaps, entirely complete. In it he claimed he had cancelled Brantford only because, having been ill earlier in the tour, he was too exhausted to undertake an all-night train journey to the city.12

On the morning of 29 December, Churchill arrived in Toronto and secured the legal services of Zebulon Lash, one of Canada’s most successful lawyers, before he met with Pond. While awaiting the meeting at Rossin House, Pond spoke with a reporter saying that his lecturer was a “genius,” but an “excitable genius” in regard to money. He added that while Churchill was now a young man, “when he is Prime Minister he will know more.”13 The conference began at 10:30 that morning and lasted for two and a half hours, with Houston arriving midway. With the assistance of Lash, matters were apparently resolved to Churchill’s satisfaction. After the Toronto lecture, his fees were apparently now to be paid on a percentage basis. Having reached an agreement, both Pond and Churchill released statements denying the lecturer had threatened to cancel the tour, with the American adding a complete denial of the interview that had been reported to have taken place the previous day. He said the statement attributed to him was “incorrect, entirely unauthorized by me, and unwarranted.”14

Life Lesson

After the “most unpleasant squabble” with Pond, Churchill wrote his mother that he was “not in the best of spirits.” The tour was “unpleasant work,” and Pond was “a vulgar Yankee impresario.” He did take pride that “there is not one person in a million who at my age could have earned £10,000 without capital in less than two years.”15

Despite the tempest, the evening’s lecture to a 4,000-strong audience at Toronto’s Massey Hall went ahead as scheduled. As a preface to his usual lecture, Churchill nervously denied reports that he had cancelled the Brantford engagement for “sordid” motives.16 With the issue of the fees resolved, the remaining Canadian and American dates were completed over the next month, with the final lecture of the tour held on 31 January at Carnegie Hall in New York.

Despite high hopes at the outset, Churchill had made a disappointing £1,600 from the lectures. Writing to Pond on the last day of the tour, he expressed a fear that he had been “unreasonable,” but he did think Pond had poorly managed the tour. Two days later Churchill sailed for England and the opening of Parliament. He retained regrets about the tour. Six years laterm, speaking in London with the future Canadian prime minister Mackenzie King, whom he had met in Ottawa, Churchill laughed and remarked, “I did make a frightful ass of myself on that trip, didn’t I?”

Endnotes

1. Randolph S. Churchill, ed., The Churchill Documents, Volume 2, Young Soldier, 1896–1900 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1967), p. 1219.

2. Michael McMenamin and Curt J. Zoller, Becoming Winston Churchill: The Untold Story of Young Winston and His American Mentor (Westport: Greenwood, 2007), p. 154; Paul Fatout, Mark Twain on the Lecture Circuit (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1966), p. 271.

3. Winston S. Churchill, A Roving Commission (New York: Scribner, 1940), p. 359; Winston S. Churchill, “What the Americans Think About the Boer War,” Collier’s, 26 January 1901, p. 3.

4. MMS 624, James B. Pond Papers, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library, Newark, DE. Hereafter cited as Pond Papers.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.; Washington Post, 15 December 1900; CHAR 28/26/77–79, Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge.

7. New York Tribune, 19 December 1900; Pond Papers.

8. CHAR 28/26/77–79; Pond Papers; Michael Shelden, Young Titan: The Making of Winston Churchill (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013), p. 21.

9. CHAR 28/26/80–82; Fall River Daily Herald, 22 December 1900.

10. CHAR 28/26/80–82.

11. Pond Papers.

12. CHAR 28/26/80–82; Pond Papers; Boston Sunday Post, 30 December 1900; New York Times, 29 December 1900.

13. Toronto Daily Star, 29 December 1900.

14. CHAR 28/26/80–82; Pond Papers; Toronto Daily Star, 31 December 1900.

15. CHAR 28/26/80–82.

16. Toronto Globe, 31 December 1900.

17. McMenamin, p. 156; Churchill Lectures in America, www. jamescumminsbookseller.com, accessed 9 March 2016; Terry Reardon, Winston Churchill and Mackenzie King: So Similar and So Different (Toronto: Dundurn, 2011), p. 30.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.