Finest Hour 173

Tourism, Politics, Painting, and Personal Staff: Churchill’s Many Links to Switzerland

August 14, 2016

Finest Hour 173, Summer 2016

Page 28

By Werner Vogt

Werner Vogt wrote his PhD dissertation about Churchill’s pictures in Switzerland’s leading daily Neue Zürcher Zeitung. The author of numerous newspaper articles and books, his latest book, about Churchill’s relationship to Switzerland, is reviewed on page 41.

It would be pretentious to assume that Switzerland played a major role in Winston Churchill’s life. Nevertheless he had many links to Switzerland, starting with his first travel abroad and finishing in the last year he lived, when his friend and supplier of his oil paints Willy Sax died shortly before him. For the Swiss people Churchill became a hero in 1940, and when he visited the city of Zurich on 19 September 1946 tens of thousands of people were cheering along the streets. The Swiss people’s gratitude was limitless. They made his drive through the city a triumphal parade. Never before and never after Churchill have the Swiss paid tribute to a great man like this.

2024 International Churchill Conference

A Most Tiring Mountain

Churchill’s first encounter with the Swiss and their homeland happened when he visited the country as a tourist in the summers of 1893 and 1894 together with his brother Jack and their tutor, Mr Little. These were in fact Churchill’s first travels abroad as a young man. He had a keen eye for the beauty of nature and wrote a series of enthusiastic letters to his mother, wherein he described the astounding scenery of the Swiss mountains and lakes but also some cities, which were to his liking. He even went so far as to climb Monte Rosa in the Valais, a substantial but by no means difficult mountain in the Canton of Valais. In a letter to his mother Churchill wrote:

While in Zermatt I climbed the Monte Rosa. It was not dangerous.…More than 16 hours of continual walking. I was very proud & pleased to find I was able to do it and to come down very fresh. It is a most tiring mountain—mainly on account of the rarification of the air on the long snow slopes. There were several Sandhurst and Harrow boys at Zermatt and they climbed Dent Blanche—the Matterhorn and the Rothhorn—The most dangerous and difficult of Swiss mountains. It was very galling to me not to be able to do something too, particularly as they swaggered abominably of their achievements. I had to be content with toilsome but safe mountains. But another year I will come back and do the dangerous ones.1

Churchill’s first experience of Switzerland was, however, not an entirely positive one. Swimming in Lac Léman, the Lake of Geneva, he feared for his life when, swimming in the middle of the lake, a thunderstorm developed. The rowboat he and a colleague had left unattended was blown away. Fortunately, young Churchill was a good swimmer and was able to reach the boat in a desperate effort. Happily, both young men survived the ordeal.

Alpine Retreat

The next series of encounters with Switzerland came about ten years later. In 1904, 1906, and 1910 Churchill spent long summer holidays in the villa of his friend and mentor Sir Ernest Cassell. Cassell loved the area of the Aletsch glacier and had a spacious country home constructed on the Riederalp, virtually in the middle of nowhere. Churchill as a young minister spent weeks on end there alone, or with his mother, and eventually with Clementine. He passed his days going for extended walks and hikes with Sir Ernest, reading, writing correspondences, and playing cards. Apparently Churchill, soon after he had arrived, had a clash with the local farmers, who drove their cattle past Cassel’s villa early in the morning. The young politician, who was not an early bird, was woken up and seriously annoyed by the sound of the bells and shouted at the peasants out of his bedroom window. Of course they did not understand a word, and Cassell had to negotiate a feasible way forward. Assisted by some monetary compensation, the peasants agreed to stuff straw into the cowbells, when they walked past the villa so the VIP guest from London was able to sleep in. Apart from the cowbells, Churchill loved the place. In a letter to his mother he wrote:

I sleep like a top & have not ever felt in better health. Really it is a wonderful situation. A large comfortable 4 storied house—complete with baths, a French cook & private land & every luxury that would be expected in England—is perched on a gigantic mountain spur 7,000 feet high, and it’s the centre of a circle of the most glorious snow mountains in Switzerland. The air is buoyant and the weather has been delightful.2

Respected Minister

Given his early affinity with Switzerland, it is astonishing that Churchill was not to return for thirty-six years. An increasing workload, a growing family, and the outbreak of the First World War were probably the main reasons to leave the Alpine republic aside, to say nothing of the death of his mentor Sir Ernest Cassell in 1921. Being distant from Switzerland in miles, however, by no means meant being distant from the country in mind. Although Switzerland has no access to the sea, the country crossed Churchill’s mind every now and then even when he was First Lord of the Admiralty during the Great War.

As for the Swiss, Churchill for the political and economic elite became a known name in the twenties, when the foreign correspondents of Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ)—the country’s finest newspaper—reported about Churchill the minister, especially when he was Chancellor of the Exchequer. It is interesting to note that during Churchill’s “Wilderness Years” (1929–39) many of his articles and comments were printed in German translation by NZZ. When Hitler and the Nazis came to power in 1933, pressure on the German-speaking neighbouring countries began to rise accordingly. With the free press extinct in Germany, the Nazis hated the fact that in Switzerland there still was a free press, which reported in their language. During the Nazi era (1933–45) and especially during the Second World War, it was forbidden in Germany and punishable by death to read Swiss newspapers or to listen to Swiss radio stations. Seen in this light, it took courage for NZZ editor-in-chief Willy Bretscher to publish Churchill until the end of 1938. Bretscher had been a foreign correspondent in Berlin in the late 1920s, and as an experienced political observer he had seen the rise of the Nazi beast. By printing Churchill’s articles he expressed his own opinion. NZZ reported anything and everything Churchill did or said during the war. Every speech was announced, briefly summarised, printed in full length, and finally all the reactions were reported too. The Nazi threat continually sharpened the minds of the newspaper men in Falkenstrasse 11, Zurich, address of NZZ.

Switzerland at Bay

Obviously Switzerland was not at the centre of Churchill’s attention when he became Prime Minister in 1940. But after the fall of France, Switzerland was the only remaining democracy in the centre of Europe, Sweden playing the same role in the North of the continent. The position of Switzerland was particular, inasmuch as it was surrounded by hostile powers (Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy) or by countries under Nazi occupation (Austria and France). This fact meant that governing Switzerland was a constant balancing act between demonstrating the power and the will to resist by mobilising the army and guarding the borders on the one hand and being pragmatic enough in trade relations not to provoke a Nazi attack. Many studies written since 1945 have proven that Switzerland’s neutrality was a “biased neutrality” in the sense that the country delivered far more weapons and industrial goods which were relevant for the armament industry to Germany than to the United Kingdom. Why? Switzerland was vitally dependent on imported raw materials, having none of its own. And be it coal, steel, or oil—all imported goods needed by the Swiss economy passed through Germany.

So why was the country not invaded in the summer of 1940 when Germany had the necessary number of divisions ready next to the Swiss borders? There are a number of reasons. First, there was no immediate strategic necessity, given that thousands of tons of transports between Germany and Italy passed unhindered through the Swiss railway infrastructure. Second, given Hitler’s plan to attack the Soviet Union, there was no need to bind important military forces for the occupation of Switzerland. Third, given Switzerland’s claim to defend itself, the Swiss Army would have made all efforts to inflict fatal damage to the crucial transport infrastructure, particularly the bridges and railway tunnels on the North-South corridor upon which the Nazis heavily depended.

It is obvious that the policy of the Swiss government to keep the country out of war and enter the conflict only if attacked has nothing heroic to it at first sight. Nevertheless, Churchill had a considerable understanding for the Swiss position. In a letter to his Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, he wrote in December 1944:

Of all the neutrals, Switzerland has the greatest right to distinction. She has been the sole international force linking the hideously sundered nations and ourselves. What does it matter whether she has been able to give us the commercial advantage we desire or has given too many to the Germans, to keep herself alive? She has been a democratic state, standing for freedom in self-defense among her mountains, and in thought, in spite of race, largely on our side.3

Another indication of Churchill’s sympathy towards Switzerland is the fact that he strongly argued against a breach of Switzerland’s neutrality, as suggested by Soviet ruler Joseph Stalin at the Yalta conference. Stalin foulmouthed the Swiss as “swine” and suggested the Allies march over Swiss territory, if this were to speed up their advance against Nazi Germany.4

“Let Europe Arise!”

After the war a group of Swiss industrialists wanted to invite Churchill for a painting holiday on the shores of Lake Geneva. A beautiful country estate was rented for him, the villa Choisi at Bursinel. The Churchills (Winston, Clementine, Mary, and their entourage) arrived in Geneva on 23 August 1946, welcomed by cheering crowds at the airport. The first three weeks were in fact a country retreat, interrupted only by brief visits to Geneva, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and Lausanne. Apart from painting in the gardens, Churchill received visitors and was busy with a huge correspondence. But, above all, he wanted to make an important speech in Zurich, the last city on his itinerary.

On his way to Zurich, Churchill first visited the Swiss capital, Bern, where he was enthusiastically welcomed by tens of thousands of people. But this was only a foretaste of what was going to happen in Zurich. As Churchill drove through the city in an open limousine, he was given a hero’s welcome. Again tens of thousands of people wanted to pay tribute to the great man, and since school was called off, thousands of pupils and students watched him drive past, waving their flags and throwing roses into his car. The warm welcome of the common people compensated for the fact that—for all kinds of silly reasons—the University of Zurich declined to award him an honorary doctorate.

Churchill’s Zurich speech, ending with the exhortation “Let Europe arise!”, is certainly one of his most important post-war statements, on par with his address in Fulton, Missouri. What is interesting, though, is the fact that Churchill’s enthusiastic call for some sort of United States of Europe is put into perspective by his remark that Great Britain was going to be outside of this new construction, given that it had the Commonwealth and the “special relationship” with the United States of America.

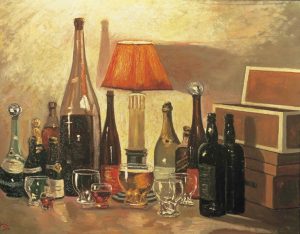

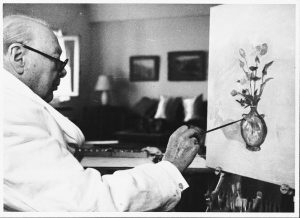

The Painting Connection

A very strong connection between Churchill and Switzerland happened to be an artistic one. Soon after he started painting, he was introduced to the Swiss painter and adviser to wealthy collectors Charles Montag. Their first encounter in 1915 must have been memorable since Churchill showed Montag a few of his early paintings, which led Montag to the sardonic remark: “If you are as strong in politics as you are in painting, Europe is bust.”5 Churchill after a deep breath roared with laughter, and a life-long friendship began. It was in fact Montag who in 1945 was instrumental in convincing Churchill that he should accept an invitation for a painting holiday by the Swiss.

Another strong connection in the field of art evolved out of his visit to Zurich in 1946. For some years already, Churchill had painted with colours produced by Sax Farben in Urdorf near Zurich. Churchill wanted to meet the man whose oil and tempera colours he liked so much. So Willy Sax, the company owner, met him in the Grand Hotel Dolder on the day of the Zurich speech. Out of this encounter an astonishing friendship developed, which lasted until the two men died, Sax half a year before Churchill. Sax was invited to Chartwell several times, introduced Churchill to famous Swiss painters like Cuno Amiet, and spent painting holidays with Churchill in the South of France.

The Kitchen Connection

There is yet a further Swiss connection unknown to high politics. Winston and Clementine Churchill developed an affection for Swiss staff, especially after the Second World War. A considerable number of young ladies from Switzerland worked in Chartwell as cooks, kitchen aides, or maids to the master or the lady of the house. Apparently the Churchills liked the Swiss way of cooking and the discipline the “Swiss girls” had. The Prime Minister was especially touched when “the Swiss girls” Lilli Wyss (cook) and Liselotte Kaufmann (kitchen aide) surprised him with a basket of home-coloured Easter eggs in 1952.6

Highest Respect for Churchill

To this day Winston Churchill is spoken about with the highest respect in Switzerland and not just by the fast-diminishing war generation. Young and middle-aged entrepreneurs often answer the question “With which historical figure would you like to dine?” with the reply, Winston Churchill. I am personally convinced that I owe my life to him. My father (1910–1994) served as an infantryman in Schwaderloch next to the River Rhine—in shooting distance to the German Reich. Most probably he would not have survived any Nazi invasion. Thank you Mr. Churchill!

Endnotes

1. Randolph S. Churchill, ed., Winston S. Churchill, Companion Volume I, Part 1, 1874–1895 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1967), pp. 517–18.

2. Randolph S. Churchill, ed., Winston S. Churchill, Companion Volume II, Part 1, 1901–1907 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1969), p. 450.

3. Christian Leitz, Nazi Germany and Neutral Europe during the Second World War (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000), p. 175.

4. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, Vol. VII, The Road to Victory 1941–1945 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1986), p. 1027.

5. Max Sauter, Churchills Schweizer Besuch 1946 und die Zürcher Rede (Herisau: Schläpfer and Co. AG, 1976), p. 14. I have translated from the original, since Montag spoke in French.

6. Werner Vogt, Winston Churchill und die Schweiz: Vom Monte Rosa zum Triumphzug durch Zürich (Zürich: Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 2015), p. 198.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.