Finest Hour 172

“Squalid Nuisance”? Nye Bevan’s Finest Hour

June 12, 2016

Finest Hour 172, Spring 2016

Page 20

By John Campbell

The conventional narrative of the Second World War tends to assume that from the moment he succeeded Chamberlain in May 1940 and rallied the nation with his heroic defiance when Britain stood alone against the Nazi threat, through to the eventual victory of the Allies five years later, Churchill’s ascendancy within Britain was unquestioned.

The conventional narrative of the Second World War tends to assume that from the moment he succeeded Chamberlain in May 1940 and rallied the nation with his heroic defiance when Britain stood alone against the Nazi threat, through to the eventual victory of the Allies five years later, Churchill’s ascendancy within Britain was unquestioned.

It is true that he never faced a serious parliamentary challenge nor, even in the darkest days of 1941–42, any plausible rival who might have displaced him, as Lloyd George supplanted Asquith in the middle of the First War. Nevertheless there was a good deal more grumbling, and more unrest in many parts of the country, than is generally remembered in the warm myth of national unity. During the period of electoral truce between the major parties the coalition government lost ten by-elections to a variety of mainly left-leaning Independents: a little-noticed undercurrent of dissent that accurately presaged Labour’s landslide victory in 1945, which so shocked observers who assumed that the electorate would naturally, as in 1918, register its gratitude to the great war leader.

If there was one man who not only anticipated this historic upset but, by his persistent criticism of Churchill’s leadership, contributed to it more than any other, it was the left-wing Labour MP Aneurin “Nye” Bevan. These days Bevan is remembered primarily as the architect of the National Health Service and, on the left, as the socialist hero to whose mantle Labour leaders still lay claim, even when they have long rejected socialism as Bevan understood it.

It was as a determined critic of Churchill’s war leadership, however, that Bevan first achieved national prominence. Elected Member of Parliament for Ebbw Vale in 1929, he was largely self-taught with an essentially Marxist view of history. But he was also an unshakeable democrat who believed that socialism in Britain would be achieved peacefully and democratically. It was with this confidence that he saw the war against Hitler not simply as a fight for national survival but as an opportunity to advance the victory of socialism at home and abroad.

A People’s War

At first Bevan welcomed Chamberlain’s replacement by Churchill in May 1940. A spell-binding orator himself, he could not but admire Churchill’s great speeches after the retreat from Dunkirk. But already his view of Churchill’s limitations was caustic. For all the magnificence of Churchill’s language, Bevan believed, the Prime Minister was rooted in the past:

2024 International Churchill Conference

What he did not do, and what he could not do, was to summon the future. For Mr Churchill is the spokesman of his order and of his class, and that class and that order is dying. That is why Mr Churchill ennobles retreat and can rally the nation to make its stand here in this island, but he cannot unfold for us the plans for victory, because there is not another victory left in the order to which he belongs, and of which he is the last distinguished representative.1

Bevan wanted a “people’s war,” leading to the replacement of the old order. He supported Labour joining Churchill’s government, but thought it should do so only on its own terms, by insisting on the immediate nationalisation of basic industries in order to put the economic resources of the country wholly at the disposal of the state. “War aims begin at home,” he declared. “If the Tory members of the Government carry their defence of private property rights to the extent of refusing the public ownership of the industries I mentioned last week, then we shall lose the war.”2 He opposed the electoral truce, and throughout the war castigated his own leaders for failing to fight hard enough for Labour’s distinctive aims.

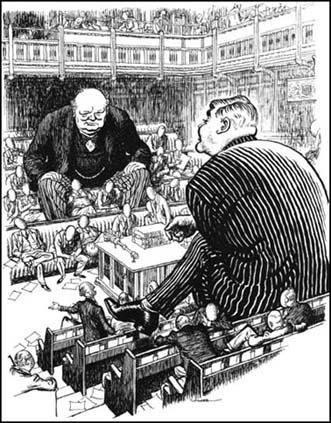

But his main fire was increasingly directed at Churchill, in particular his combining of the roles of Prime Minister and Minister of Defence. This gave Churchill a position far stronger than Lloyd George in 1917–18. But his dominance should not put him beyond criticism:

In a democracy, idolatry is the first sin. Not even the supreme emergency of war justifies the abandonment of critical judgement…. To surrender all to one man is to risk being destroyed by him.3

Bevan particularly condemned Churchill for having himself elected Conservative leader after Chamberlain stepped down in October 1940. “Once more,” he raged, “the Tory caucus drapes itself in the national flag.”4 Henceforth he regarded Churchill merely as a party leader, not as the leader of the whole nation.

When Hitler’s invasion of Russia brought the Soviet Union into the war in June 1941, Bevan immediately demanded a second front to take the pressure off “those lion-hearted Russians.”5 If after two years of war Britain was unable to launch a second front, then that was a disgrace, which he blamed on Churchill—“a Prime Minister who is completely illiterate in all matters connected with industry and who has come to think in terms of perorations and rounded verbiage.”6 People, he alleged, were “beginning to say that he is undoubtedly a superb defence Prime Minister, but he shows no signs of being a victory Prime Minister.”7 He condemned what he called Churchill’s “one-man government” and called for a proper War Cabinet—“a War Cabinet of ministers without departmental responsibilities, who can talk back to the Prime Minister.”8

Bevan constantly defended the right and duty of Parliament to criticise the Prime Minister—“Social institutions, like muscles, depend upon their use. If they are not used they become atrophied”—and rejected the idea that “amateur” strategists like himself had no credentials to criticise the conduct of the war.9 “These gibes are silly….Strategy is merely applied common sense.”

It is the obligation of this House to discuss major strategy and for hon. Members to say otherwise means that they are undermining the very foundation of representative government…. Representative government is government of the experts by the amateurs and always has been.10

Parliament’s job, in war as much as in peace, was to hold the Government to account: “The right hon. Gentleman has become irresponsible, because he has not been sufficiently kicked in this House.”11

Trying Times

Despite the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor bringing America into the alliance in December 1941, the war continued to go badly for Britain for most of 1942. In North Africa, Auchinleck was driven back by Rommel, while Japan established naval superiority in the Pacific and captured Singapore. Bevan pinned the responsibility for these losses on Churchill’s strategic blunders. The Prime Minister might be the symbol of national unity:

But he is not the sole residue [sic] of wisdom and knowledge as to how that unity should be directed. The building up of this man’s reputation has gone as far as the safety of the country warrants….If the Prime Minister insists on making himself responsible for all questions of higher military strategy, then he must be ready to face accusations directed against that strategy….How long can we afford a succession of oratorical successes accompanied by a series of military disasters?12

In July, following the fall of Tobruk, Churchill faced his most serious parliamentary challenge. The debate quickly collapsed in ridicule when the mover of the critical motion proposed that the Duke of Gloucester be appointed commander-in-chief, and it attracted only twenty-five votes. But the most powerful speech was made by Bevan, with a detailed and well-informed critique of the strategy and weaponry of the North African campaign, which he alleged was too defensive because British staff officers were not trained in the Germans’ Blitzkrieg technique of coordinating land and air forces in a war of movement. He repeated the taunt, which he claimed was “on everyone’s lips,” that if Rommel had been in the British army he would still be a sergeant; and called for a purge of the War Office, beginning at the top: “The fact of the matter is that the British Army is ridden by class prejudice…. If the House of Commons has not the guts to change it, events will….It is events which are criticising the Government. All that we are doing is giving them a voice.”13

Two months later Bevan made his most personal attack on the Prime Minister. He mocked what he called his “turgid, wordy, dull, prosaic and almost invariably empty” speeches. He objected to Churchill’s habit of wearing of military uniforms: “I wish he would recognise that he is the civilian head of a civilian government, and not go parading around in ridiculous uniforms.” And he castigated Churchill’s complaint that the press gave too much space to his critics.

Two months later Bevan made his most personal attack on the Prime Minister. He mocked what he called his “turgid, wordy, dull, prosaic and almost invariably empty” speeches. He objected to Churchill’s habit of wearing of military uniforms: “I wish he would recognise that he is the civilian head of a civilian government, and not go parading around in ridiculous uniforms.” And he castigated Churchill’s complaint that the press gave too much space to his critics.

I say that this amounts to political intimidation without precedent in the history of this country and is evidence of the increasing paranoia of the Prime Minister’s psychology, for which the docility of the House of Commons is responsible. The time has come when we should make this man realise that the House of Commons is his master.14

More substantially, he continued to criticise the conduct of the war, in terms that many military historians have subsequently upheld. He condemned the so-called “strategic” bombing of Germany: “I have found no reason at all why the German population should be more ready to succumb to night bombing than the British public….The idea of sending out thousands of bombers every night to bomb Germany just will not work.”15 And like many others in 1942, impatient for the opening of a second front in Europe, he derided the diversion of effort to North Africa as irrelevant and futile. Finally, he demanded that Churchill should go:

We must recognise that a change in Government…is necessary if our people are to sustain a fourth winter of war with the same courage and buoyancy as they did the first, second and third winters….I do not conceal from the Committee that the Prime Minister’s continuance in office is a major national disaster.16

He did not, however, suggest who might take Churchill’s place.

“A Gift to Goebbels”

When the tide finally turned with Montgomery’s victory at Alamein, Bevan naturally rejoiced. But he nevertheless criticised Churchill’s order that church bells be rung in celebration as premature and foolish. He attributed the belated success to the correction of precisely those faults of weaponry and tactics that he had condemned in July; and he still denied Churchill the credit: “The Prime Minister always refers to a defeat as a disaster as though it came from God, but to a victory as though it came from himself.”17 Even in Churchill’s hour of vindication Bevan could not refrain from carping.

During the latter part of the war, after the Russian victory at Stalingrad and the full commitment of the Americans had made the ultimate defeat of Hitler certain, Bevan never let up his criticism of Allied strategy. He dismissed the Italian campaign as strategically misconceived—far from Italy being the “soft underbelly” of the Axis, he claimed, “we are climbing up his backbone.”18 Bevan suspected Churchill’s true motivation, in both Italy and Greece, as being to restore the monarchies instead of supporting democracy: “Wherever he sees a king he wants to put him on his throne, and if he sees one tottering he wants to prop him up.”19 He condemned the statement that the Allies would accept nothing less than “unconditional surrender” as “a gift to Goebbels” which would only encourage the Germans to fight to the last man, instead of undermining their will to fight by offering them a better future.20 And as the war came to an end he mocked Churchill’s posturing as the equal of Roosevelt and Stalin, warning that Britain after the war would be a second-rank military power and should take on the leadership of Western Europe instead. He opposed the Labour leadership’s wish to prolong the coalition because he confidently—and almost alone—anticipated Labour’s victory in 1945. He was determined to reassert Labour’s independence, insisting that the election was about building a new future, not a vote of thanks to the Prime Minister. He even claimed that if democracy survived it would be “in spite of Winston Churchill,” not because of him.21

Churchill called Bevan “a squalid nuisance,” and his sustained carping was widely condemned as unpatriotic, if not positively treasonable.22 A rhyme expressing this view was attributed to A. A. Milne:

Goebbels, though not religious, must thank Heaven, For dropping in his lap Aneurin Bevan.

Principled Opposition

Some of Bevan’s pursuit of Churchill was indeed offensively personal and wide of the mark. Right or wrong, however, he played an honourable role in the war which deserved to be acknowledged with more grace, at least when it was all over, than Churchill allowed. In a war for democracy, it was healthy that not merely democratic forms but a real clash of argument should be maintained. There was something heroic in the persistence with which Bevan—and others, but Bevan was the most persistent and principled— insisted on providing critical opposition at a time when the official Opposition interpreted their function principally as to give loyal support to the Government. Naturally hard-pressed ministers did not appreciate it; but Bevan, by his relentless questioning and his forcefulness in debate strove—successfully—to keep parliamentary government a reality.

Bevan was wrong only in imagining that the yearning he correctly felt in the country for a new settlement after the war would lead on after 1945 to the establishment of a fully socialist society. His confident expectation of the march of history was to be thwarted by the enduring adaptability of capitalism, and he died in 1960 a disappointed man. But his role during the war in providing principled parliamentary opposition to what might otherwise have been an overweening Government deserves recognition and respect. For all his later achievements, 1940–45 was not only Churchill’s but paradoxically also Bevan’s “finest hour.”

As well as biographies of Margaret Thatcher, Edward Heath, and Roy Jenkins, John Campbell’s books include Nye Bevan and the Mirage of British Socialism (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1987).

Endnotes

1. Tribune, 21 June 1940.

2. Tribune, 11 October 1940.

3. Tribune, 30 August 1940.

4. Tribune, 18 October 1940.

5. House of Commons, 2 July 1941.

6. Tribune, 1 August 1941.

7. Tribune, 10 October 1941.

8. House of Commons, 23 October 1941.

9. House of Commons, 23 October 1941.

10. House of Commons, 12 November 1941.

11. House of Commons, 18 December 1941.

12. Tribune, 15 May 1942.

13. House of Commons, 2 July 1942.

14. House of Commons, 9 September 1942.

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid.

17. House of Commons, 12 November 1942.

18. House of Commons, 15 December 1943.

19. House of Commons, 18 July 1944.

20. House of Commons, 29 September 1944.

21. Tribune, 6 July 1945.

22. House of Commons, 6 December 1945.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.