Finest Hour 172

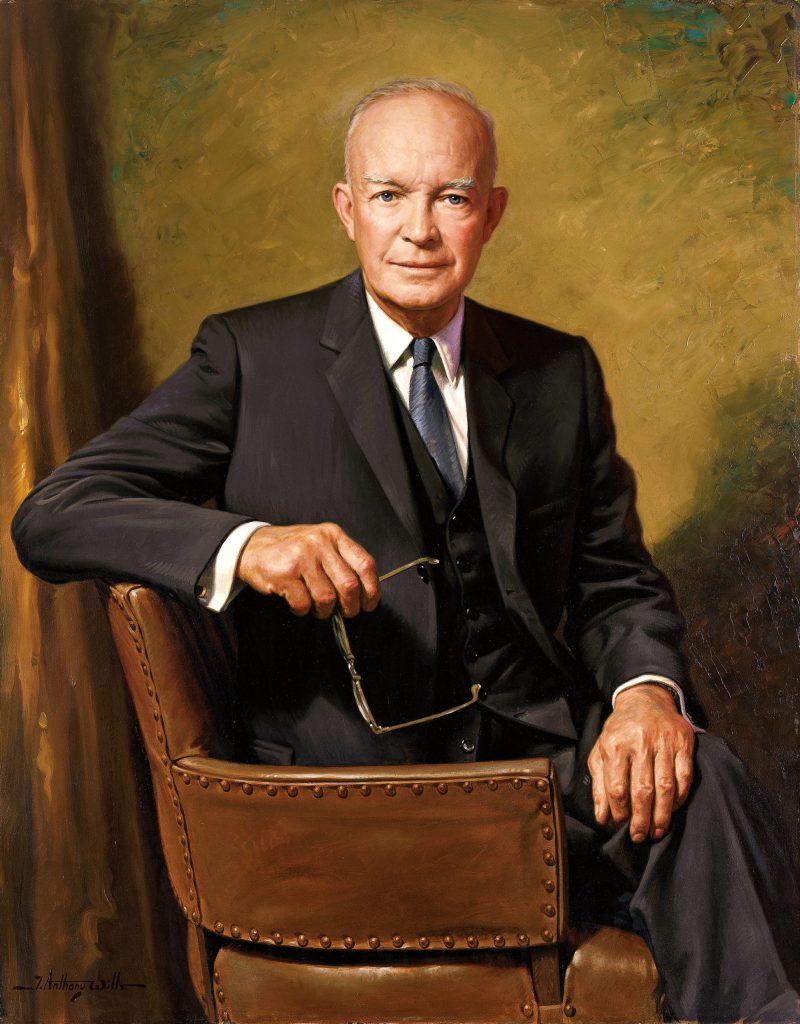

The Prime Minister and the General: Churchill and Eisenhower

June 8, 2016

Finest Hour 172, Spring 2016

Page 15

By Lewis E. Lehrman

When Winston Churchill died in January 1965, President Lyndon Johnson decided not to attend the funeral. Startled by LBJ’s decision, Dwight D. Eisenhower was equally surprised that he, the top Allied commander in Europe during the Second World War, was not named to the official funeral delegation of the United States. No matter, the former American president received a personal invitation from the Churchill family to attend the funeral of his friend, the former British Prime Minister.

Despite different backgrounds, the Prime Minister and Eisenhower had much in common. The General was a good writer. He enjoyed the writer’s art. He once turned down an offer to be a military correspondent that would have paid nearly seven times his army salary. Like Churchill, Eisenhower would write important memoirs of the history of the Second World War. The two had first met at the White House on 22 June 1942, when the Prime Minister also met General Mark W. Clark. “I was immediately impressed by these remarkable but hitherto unknown men,” recalled Churchill.1 The British would have their own reasons to be impressed by the American Commander over the next three years. Eisenhower, as the Prime Minister would affirm, embodied Anglo-American cooperation during the war.

By war’s end, both leaders were heroes. “Humility must always be the portion of any man who receives acclaim earned in blood of his followers and sacrifices of his friends,” Eisenhower told a Guildhall audience on 12 June 1945. “My most cherished hope is that, after Japan joins the Nazi in utter defeat, neither my country nor yours need ever again summon its sons and daughters from their peaceful pursuits to face the tragedies of battle. But—a fact important for both of us to remember—neither London nor Abilene [the general’s hometown]…will sell her birthright for physical safety, her liberty for mere existence,” the Kansas native told the London crowd.2

During the war, the General and the Prime Minister had collaborated to build up American troops in Britain for the cross-channel invasion. They worked together to launch the invasions of North Africa, Italy, and France. Churchill often invited the Allied commander to lunch at 10 Downing Street on Tuesdays and to Chequers for weekends. They did not always agree but they always worked in tandem.

2024 International Churchill Conference

Early on, Churchill worried about the consequences of a premature D-Day landing, which Eisenhower would command in June 1944. The British Prime Minister told the American general: “When I think of the beaches of Normandy choked with the flowers of American and British youth and when in my mind’s eye I see the tides running red with their blood I have my doubts—I have my doubts, Ike, I have my doubts.”3

The Prime Minister proved correct in opposing a premature invasion in 1942 or 1943. In his war memoirs, Eisenhower observed: “While Winston might at times express his doubts in the close confines of an intimate meeting, he would never show pessimism or hesitancy in public.”4 Eisenhower wrote that “among ourselves, the Prime Minister would add, following his expression of doubt, ‘We are committed to this operation of war. And we must all, as loyal Allies, do our very best to make it a success.’”5

The General would listen to the Prime Minister, but ignore him when necessary. Ike knew he could count on the full backing of President Roosevelt and US Army Chief of Staff, George Marshall. At key points Churchill would come to Ike’s defense. During the climactic Battle of the Bulge in December 1944, Churchill called Eisenhower to say he was releasing a press statement as “a mark of confidence in you.”6 Churchill would listen to Eisenhower, but he ignored Ike’s cautious orders when the Prime Minister insisted upon getting too close to the German front in 1945. Eisenhower would block the Prime Minister’s attempts to cross the Rhine personally in late March. After the General departed, Churchill declared: “I’m now in command. Let’s go over.”

Churchill differed with Eisenhower about the importance of capturing Berlin ahead of the Russians. “The idea of neglecting Berlin and leaving it to the Russians to take at a later stage does not appear to me to be correct,” Churchill wrote.7 The Prime Minister was practiced in the art of “judge-shopping.” If one American official did not give him the answer he sought, Churchill would find another. But he usually discovered he could not undo Eisenhower’s military decisions. After his election defeat, Churchill left office at the end of July 1945. Eisenhower then arranged for him to use a villa near Cannes to decompress from five years of strenuous war leadership. Eisenhower’s son noted: “Ike was always conscious that the Prime Minister was a piece of history.”8

Nearly two decades later in his BBC eulogy for Churchill, Eisenhower said: “With no thought of the length of time he might be permitted on earth, he was concerned only with the quality of the service he could render to his nation and to humanity. Though he had no fear of death, he coveted always the opportunity to continue that service.” Eisenhower declared of the Prime Minister: “Among all the things so written or spoken, there will ring out through the entire century one incontestable refrain: Here was a champion of freedom.”9

Lewis E. Lehrman, co-founder of the Gilder-Lehrman Institute of American History, is author of Lincoln at Peoria: The Turning Point (Stackpole, 2008) and Lincoln ‘by littles’ (TLI Books, 2013).

Endnotes

1. Robert H. Pilpel, Churchill in America, 1895–1961 (New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1976), p. 170.

2. John S. D. Eisenhower, General Ike: A Personal Reminiscence (New York: Free Press, 2004), p. 184.

3. James C. Humes, Eisenhower and Churchill: The Partnership That Saved the West (New York: Forum Books, 2001), p. 180.

4. Dwight D. Eisenhower, At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends (New York: Doubleday, 1967), p. 273.

5. Ibid.

6. Harry C. Butcher, My Three Years with Eisenhower (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1946), p. 734.

7. Omar N. Bradley and Clay Blair, A General’s Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1983), p. 421.

8. John S. D. Eisenhower, General Ike, p. 180.

9. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Post Presidential Papers, 1961–1969, 1965 Principal File, Eisenhower Presidential Library, Abilene, Kansas.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.