Finest Hour 172

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – Our Man at the Front

June 12, 2016

Finest Hour 172, Spring 2016

Page 40

Review by Chris Sterling

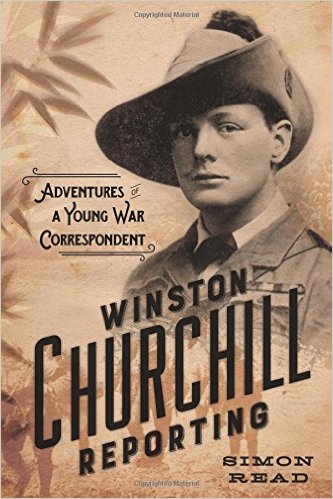

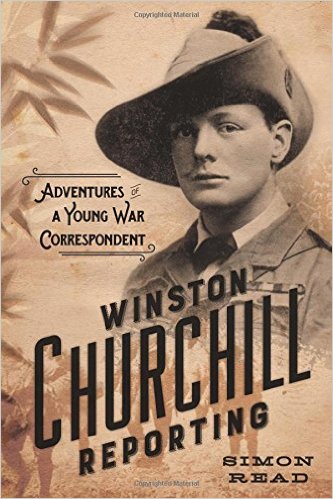

Simon Read, Winston Churchill Reporting: Adventures of a Young War Correspondent, Da Capo Press, 2015, 309 pages, $26.99. ISBN 978-0306823817

Read, a former California journalist born in England, begins his book with a clear disclaimer: “I don’t consider this a biography or a work of history—though it contains elements of both. It is, instead, a true tale of adventure featuring Winston Churchill in the starring role. When writing the book, I described it to friends as ‘Winston Churchill as Indiana Jones’” (ix). And therein lies both the appeal and drawback of this latest addition to the ever- growing “Churchill and _____” shelf.

Read, a former California journalist born in England, begins his book with a clear disclaimer: “I don’t consider this a biography or a work of history—though it contains elements of both. It is, instead, a true tale of adventure featuring Winston Churchill in the starring role. When writing the book, I described it to friends as ‘Winston Churchill as Indiana Jones’” (ix). And therein lies both the appeal and drawback of this latest addition to the ever- growing “Churchill and _____” shelf.

Read’s breezy style stitches together the adventuresome story of Churchill’s first four wars on which the initial newspaper columns and several of WSC’s early books are based. These include his trip to Cuba to observe Spanish forces fighting rebels (1895–96), the fighting role of the Malakand Field Force in what is now Pakistan (1897), the “river war” in Sudan (1898), and the bitter South African Boer War on which Churchill reported (1899–1900). In all save the first, Churchill was also a serving officer in the British Army, an odd combination that raised eyebrows.

Churchill’s “lucky” placement in four such widespread conflicts over less than five years was no mere happenstance. His well-connected mother Jennie opened the right London doors to reach key government and army officials who surrendered to her charm and persuasion, often against their own better judgment. The seeming Churchill luck created more than a bit of envy and jealousy among many of the soldiers with whom he served.

Read provides a rollicking tale as promised, better in some places than others—indeed often best when closely paraphrasing the newspaper columns that Churchill sent back to London newspapers from his various army postings. To access those, readers may want to have close at hand the second edition of Frederick Woods’ excellent anthology of Churchill’s early wartime writing, Winston S. Churchill War Correspondent, 1895–1900 (Brassey’s, 1992). The two books are ideal companions—Woods providing the published work from which Read has drawn part of his tale. The other primary source, of course, is the first volume of the official biography and its “companions.”

2025 International Churchill Conference

The drawback is, in the end, twofold: some things are left unexplained, and there is little new here amongst the dashing and derring do. Put another way, this is a Churchill book for readers new to the stories it tells.

And the unexplained? I wonder how many readers (Churchill aficionados or not) know what a heliograph is (31)? For the record, it was a late nineteenth-century signaling device that reflected sunlight with a system of mirrors. And in a way all too typical in popular books, we read about amounts of money (as was required, for example, to take care of a horse) with no sense (save in a few cases) of what that 1890s cost is in current-value dollars. This is no minor oversight: inflation of the British pound over the last century is more than a hundredfold. So when Jenny Churchill complains about the costs of keeping Winston in the style to which he aspired (and had already grown accustomed), we lack any sense of the modern comparative value (and thus financial pressure on both of them) involved.

To his credit, Read provides five outline maps that include most of the locations discussed. While not faultless (for example, I could not find Atbara—mentioned several times in the chapter on the River War—on the map of Egypt and the Sudan), they provide real help for readers unacquainted with the regions in question. And close to fifty pages of notes at the end allow those interested to pursue the source of quotes and other information.

Read (and Churchill) make clear the ways in which the four wars differed—in whom the British colonial forces were fighting, of course, but especially in the varied battlefields. The fighting grounds all shared an oppressive sticky (or in Egypt and the Sudan, dry) heat. The incipient colonial racism of the time (that the enemy were “savages” is but one example) is made clear. The chapter relating the famous “last” British cavalry charge at Omdurman in 1898 is grippingly told, drawing in part on Churchill’s own telling of the event in The River War.

Summing up, Read generally succeeds in presenting a true Churchillian adventure tale. Many of my concerns are quibbles of detail. Churchill’s reporting and fighting roles in these late Victorian colonial wars comes through well.

Christopher H. Sterling is Professor Emeritus of Media and Public Affairs at The George Washington University.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.