Finest Hour 172

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – Not Just Hot Air

June 12, 2016

Finest Hour 172, Spring 2016

Page 41

Review by Chris Sterling

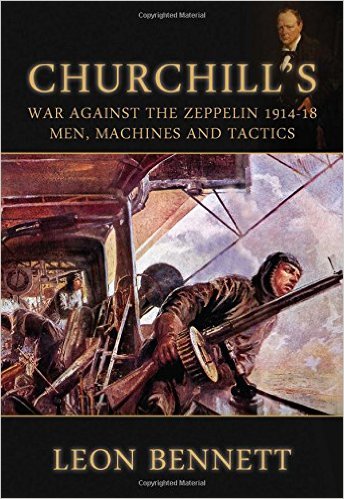

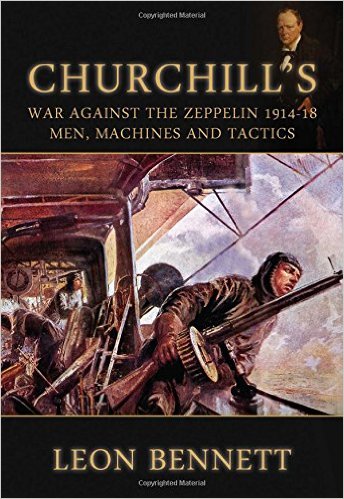

Leon Bennett, Churchill’s War Against the Zeppelin 1914–18: Men, Machines and Tactics, Helion, 2015, 406 pages, $59.95. ISBN 978-1909982840

Long interested in both airship history and Churchill, I had high expectations for this book that melds both topics. To a great extent they were met, though with a few frustrations along the way.

Long interested in both airship history and Churchill, I had high expectations for this book that melds both topics. To a great extent they were met, though with a few frustrations along the way.

Leon Bennett’s book centers on the German Zeppelin (airship) bombing raids against England (and especially London) during the First World War and the defense measures taken to meet the new air threat. German fliers tried to bomb the city for months after the war began in August 1914, but initially managed only sporadic raids against easy-to-find coastal towns. Weather was often the chief culprit—especially capricious winds that could push the huge rigid airships miles off course. Crude nighttime navigation was hit or miss, often the latter. British airships (also covered here) faced the same limitations—a key reason that Churchill, after initial enthusiasm, became a consistent critic of the technology. Despite his misgivings, however, the British continued their expensive airship program after the war until the R 101 tragedy in 1930 shut down the effort.

When the huge and clumsy Zeppelins succeeding in hitting something in the Great War, public panic far exceeded the casualties or physical damage. For here was an invasion for which, at first, there seemed no defense. Gradually the fledgling British Royal Flying Corps and Naval Air Service developed methods of fighting the floating “baby killers,” including the use of searchlights and anti-aircraft guns, plus slowly improving fighter aircraft. The airship’s chief weakness was its reliance on highly flammable hydrogen gas to provide lift. Incendiary bullets or even small bombs dropped from above a Zeppelin’s flight path could lead to flaming death for all on board (no parachutes were carried). Indeed, more than half the German airship crews died (from all causes). The cost and loss of Zeppelins finally turned the Germans to what were really the first strategic bombers—huge (for that time) twin- and four-engine bomber aircraft that proved far more deadly weapons in the last two years of the war.

When the first Zeppelin raids reached London at the end of May 1915, Churchill had been forced out of his Admiralty leadership post (over Dardanelles policy, not airship raids), and was given little say on British air defense policy. But Bennett does a creditable job assessing the ongoing raids from both sides—the weather and navigation issues faced by Zeppelin captains and the many approaches considered (only a few were taken) by the British to bring down the aerial raiders. For despite their size and relative fragility, Zeppelins were very hard to hit given the technology of the time. In text and diagram, the author makes those difficulties all too evident (locating the airship, aiming searchlights and ground guns, directing fighter aircraft, and accounting for the raider’s speed, direction, and altitude).

And those frustrations? Most serious is that Bennett too often takes his reader off on a trail of unrelated details. He devotes three pages to the pre-war Marconi scandal, for example, and more than fifteen to assessing the Kaiser’s personal psychology. In fact Bennett does not really focus on Churchill and rigid airships until he reaches page 104! An alert editor should have trimmed such tangents and corrected the author’s irritatingly consistent use of “Winston” while referring to everyone else by surname. Consistent conversion of century-old British monetary figures is essential to give readers a real sense of relative value. Some numbers receive this treatment but too many others do not. There are other nuisances: one need not capitalize “naval” or “government,” and page 120 has underlines in place of the intended pound signs in at least four places. Finally, the publisher’s sales aim seems all too clear when the cover spells out CHURCHILL at twice the font size of the title’s remaining words.

Period illustrations, on the other hand, are a strong point—including a host of Churchill-themed cartoons from Punch and other contemporary publications. Diagrams (many by the author) help to explain technical aspects of Zeppelin development, operation, and destruction. Photos are also used well, though many suffer from the poor quality of their time.

Bennett makes clear that both sides in the Great War were pushing available technology to the limits—merely hinting at what the next world war would bring. But much of that story does not involve Churchill directly—and thus he disappears from the narrative for pages at a time. In the end, the cost, complexity, and comparative fragility of the Zeppelin airship gave way to the increasingly efficient capability of the airplane.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.