Finest Hour 171

Books, Arts & Curiosities – Coming of Age in Cuba

March 20, 2016

Finest Hour 171, Winter 2016

Page 39

Review by Con Coughlin

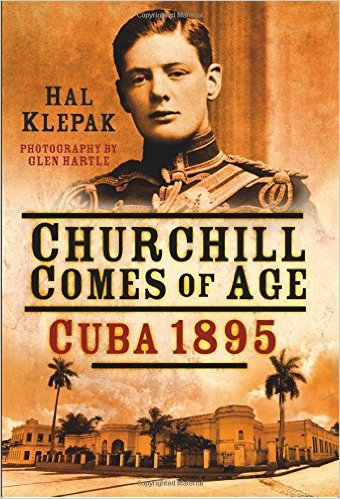

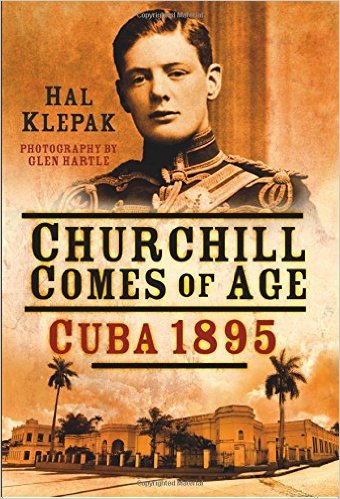

Hal Klepak, Churchill Comes of Age: Cuba, 1895, The History Press, 2015, 288 pages, £25, $46.95.

ISBN 978-0750962254

Follow this link to purchase your copy.

It is a testament to the indomitable spirit of the young Winston Churchill that, before he had even completed his basic military training, he should seek to have first-hand experience of the perils of modern warfare.

It is a testament to the indomitable spirit of the young Winston Churchill that, before he had even completed his basic military training, he should seek to have first-hand experience of the perils of modern warfare.

Churchill was twenty years old and undergoing his basic cavalry training as a recently-recruited subaltern in the 4th (Queen’s Own) Hussars when he took the quixotic decision to spend his annual vacation visiting Cuba, which was then in the midst of a brutal civil war.

2025 International Churchill Conference

Throughout his long and distinguished life, one of Churchill’s defining characteristics was his determination to go his own way, even when it met with considerable opposition. His support for the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign during the First World War, as well as his less-than-enthusiastic attitude towards the D-Day landings in 1944, are some of the more memorable instances where Churchill displayed a single-minded determination to demonstrate his independent spirit.

And so it was in 1895 when, by opting to visit Cuba as a guest of the Spanish military, Churchill first demonstrated the single-mindedness that set him apart from his military peers. For, as Hal Klepak relates in this highly readable and exhaustively researched account of young Winston’s experience of the Cuban civil war, Churchill set off on his adventure with various motives in mind, not least of which was to make a name for himself.

Churchill had only recently passed out from the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, but already his ambitions lay well beyond the confines of a military career. Even at this tender age, he was already giving serious thought to embarking on a political career, one that he hoped would exonerate his father, a leading figure in the Conservative Party, who had had a calamitous fall from grace before he eventually succumbed to illness and died in January 1895, the same month that Churchill left Sandhurst.

Klepak writes that Churchill saw the Army as the means to an end, rather than the end itself, a platform for him to win fame and glory that would ultimately lay the ground for a political career. Thus, rather than being contented with the ordinary demands of military life, Churchill was desperate for adventure, one, moreover, that involved military action and a chance to prove his mettle on the battlefield.

Thus the Cuban conflict, which had erupted earlier that year and where Spanish government forces were attempting to suppress a highly-effective guerrilla campaign seeking independence for the island, provided the young officer with the perfect opportunity to test his mettle.

As an expert on Cuban history and politics as well as a lifelong Churchill devotee, Klepak is uniquely placed to examine this overlooked but formative period in the development of Churchill’s knowledge of modern warfare. During the course of researching his account, Klepak, a former Canadian infantry officer who has also worked as a strategic advisor to the Canadian Ministry of Defence and NATO, travelled extensively, including making several visits to Cuba where he retraced Churchill’s footsteps with his friend Glen Hartle, who also assisted with photographs and graphic design. As a result Klepak’s claim to have provided the definitive account of this little-known Churchillian episode is well founded.

Apart from Churchill’s desire to make a name for himself, Klepak argues that the young officer had other motivations for making the journey, not least of which was his strong desire to be acknowledged as having personal courage of a high order. As he wrote to his younger brother Jack shortly before sailing from Liverpool, “Being in many ways a coward—particularly at school— there is no ambition I cherish so keenly as to gain a reputation for personal courage.” And the fact that Churchill was under instructions from the Director of Military Intelligence “to collect information and statistics on various points,” and in particular to look into a new rifle round the Spanish were using, gave his visit a quasi-official designation, one that might even enhance his military career.

Please help support The Churchill Centre by purchasing your copy today.

Churchill’s Cuban adventure more than satisfied his desire to experience firsthand the thrill of battle after he joined a Spanish fighting column sent to confront the guerrillas. According to Churchill’s own account, he first came under fire on 30 November, his twenty-first birthday. “On that day for the first time I heard shots fired in anger, and heard bullets strike flesh and whistle through the air,” he later recollected. Klepak questions whether the incident occurred on Churchill’s birthday or a few days later. But what is not in doubt is that on several occasions Churchill was involved in direct engagements with the enemy, although he managed to avoid being injured in any way.

On one occasion Churchill relates how, having bedded down for the night, “I was soon awakened by firing. Not only shots but volleys resounded through the night. A bullet ripped through the thatch of our hut, another wounded an orderly outside.” As the column moved forward, it was subjected to continual sniping by the guerrillas, “making the march very lively for everybody.” Churchill was impressed by the conduct of the Spanish commanding officer: “The General, a very brave man—in a white and gold uniform on a grey horse—drew a great deal of fire onto us and I heard enough bullets whistle and hum past to satisfy me for some time to come.”

Eventually the column achieved its objective of driving the guerrillas from their positions and capturing the territory and, with the fighting drawing to a close, Churchill made his way back to Havana to start the return journey to London exhilarated by the experience.

As Klepak writes in his concluding chapter, the memories of his Cuban adventure would remain with Churchill for the rest of life. It was here that he spent his twenty-first birthday, and it was here, marching along rural Cuban roads, that he experienced his baptism under fire. In almost every sense, it was in the Cuba of 1895 that Winston Churchill truly came of age.

Con Coughlin is executive foreign editor for the Daily Telegraph and author of Churchill’s First War: Young Winston at War with the Afghans (Thomas Dunne Books, 2013).

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.