Finest Hour 171

“Bang! Bang! Bang!” Churchill on the North-West Frontier

March 8, 2016

Finest Hour 171, Winter 2016

Page 06

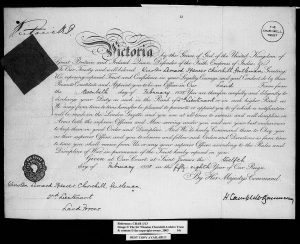

By Con Coughlin

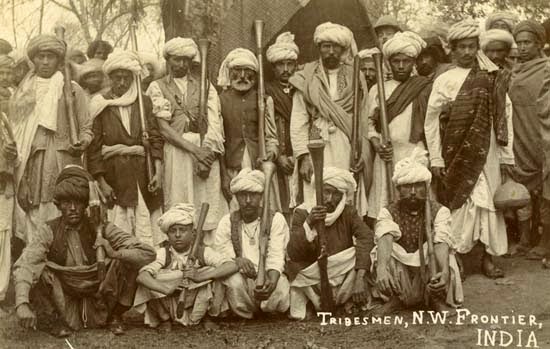

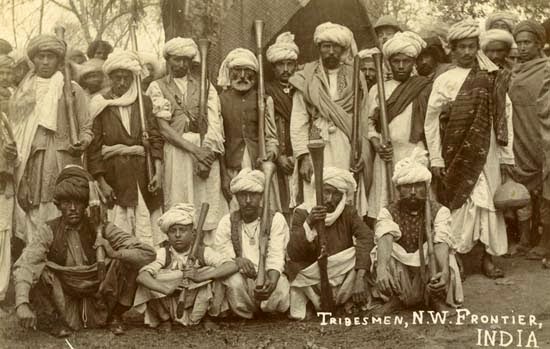

In 1897, British forces launched a bloody campaign against Afghanistan’s Pashtun tribesmen—forebears of the Taliban—on India’s North-West Frontier (now the border region between Afghanistan and Pakistan). It was the first time Winston Churchill, then twenty-two and a junior cavalry lieutenant as well as an aspiring war correspondent for the London Daily Telegraph, had taken part in military action as a combatant. The experience would have a profound bearing on his subsequent career as a writer and politician.

A week into the campaign, Churchill was still a knight of the pen, rather than one of the sword, so he concentrated his energy on finding good copy for his Telegraph dispatches. He kept himself busy by accompa- nying the daily reconnaissance patrols and observing their map-making efforts. As he told his friend Reggie Barnes, he spent most days with the 11th Bengal Lancers and the evenings in the general’s mess. When out riding with the Lancers, Churchill was always on the lookout for action, but had little luck. “I take every opportunity and have accompanied solitary patrols into virgin valleys and ridden through villages and forts full of armed men—looking furious—but without any adventure occurring. It is a strange war. One moment people are your friends and the next they are shooting. The value of life is so little that they do not bear any grudge for being shot at.”

On 12 September Churchill’s camp came under sniper fire. Churchill was having dinner with Major-General Sir Bindon Blood when “a bullet hummed by over head.” The incident strengthened Churchill’s view that the Mohmands, a local Pashtun tribe, needed to be dealt with. As he told Barnes: “After today we begin to burn villages. Every one. And all who resist will be killed without quarter. The Mohmands need a lesson, and there is no doubt we are a very cruel people.”

On 13 September, Blood dispatched two squadrons from the 11th Bengal Lancers to scout the north of the Mohmand Valley, the focus of the tribes’ anti-British revolt. The Lancers set fire to one village and, as they withdrew, came under fire from tribesmen hidden on the surrounding hillsides. It was a minor skirmish, with no British casualties, but it was a harbinger of the more serious fighting to come. Churchill was at the camp to welcome the Lancers on their return and noted, with a degree of envy: “They were vastly pleased with themselves. Nothing in life is so exhilarating as to be shot at without result.”

2025 International Churchill Conference

Churchill’s galloping around with the Lancers provided good material for his Telegraph dispatches. All the articles were signed “By a Young Officer,” and Churchill did his best to post “picturesque forcible letters,” as the newspaper’s editor had demanded, even when he had not seen a great deal. His dispatch of 5 September pays tribute to the bravery of the Pashtuns: “Their swordsmanship, neglecting guards, concerns itself only with cuts and, careless of what injury they may receive, they devote themselves to the destruction of their opponents.”

But he is less well disposed to the mullahs, who incited the violence in the first place, and was appalled by their habit of trading their womenfolk to buy rifles. “This degradation of mind is unrelieved by a single elevated sentiment,” he writes. “Their religion is the most miserable fanaticism, in which cruelty, credulity, and immorality are equally represented. Their holy men—the Mullahs—prize as their chief privilege a sort of droit de seigneur. It is impossible to imagine a lower type of being or a more dreadful state of barbarism.”

On 14 September Churchill moved seven miles west to Nawagai with the 3rd Brigade and Blood’s divisional headquarters, while the 2nd Brigade marched towards the Rambat Pass, aiming to cross it the following day. But as the 2nd Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Patrick Jeffreys, a highly decorated soldier who had fought in the Zulu wars and Burma, established camp at Markhanai, eleven miles south of the pass, it came under sustained attack.

Blood ordered Jeffreys to move against the tribesmen the next day. The following morning Jeffreys began moving up the Mohmand Valley with three columns, but he was met with strong resistance from the local Pashtun tribesmen, forcing him to withdraw.

By nightfall, the general and his small escort had been cut off, and defended themselves with some difficulty until relief arrived. The action resulted in the British sustaining nearly 150 dead and wounded, some of them subalterns no older than Churchill. As Blood later recalled in his memoirs: “As soon as I heard of General Jeffreys’ mishap, I sent for Churchill and suggested his joining the General in order to see a little fighting. He was all for it, so I sent him over at once and he saw more fighting than I expected, and very hard fighting too.”

Young Fool

Churchill’s long-standing desire to put himself in the thick of the action was finally realised on the morning of 16 September when, conspicuously riding a grey charger, he joined the 2nd Brigade of the Bengal Lancers as they moved out from their base at Inayat Kila at 6 AM and headed for the Mohmand Valley. He had bought his horse at an auction of the effects of a junior officer who had been killed earlier in the campaign. By choosing to ride a grey, Churchill was making sure that no one could fail to notice his endeavours were he to find himself in the thick of the action.

The Mohmand Valley, to the south-east of the Afghan border, is a fan-shaped cul-de-sac about ten miles in length from north to south. Traditionally it has been controlled by tribes that jealously guard their independence, and it later became a renowned stronghold for the Taliban.

The 2nd Brigade’s mission was to “chastise” the valley’s tribes by burning crops, destroying reservoirs and blowing up fortified buildings in the villages. Within the context of Major General Sir Bindon Blood’s broader campaign to restore order to the North-West Frontier, this was a routine operation designed to curtail the threat posed by one particularly troublesome group. But it was certainly not without risk.

The Afghans had learnt, over many decades of fighting, that they were no match for the British in set-piece battles. Instead, they relied on classic guerrilla tactics, withdrawing when confronted by a superior force, and then launching highly effective ambushes.

Churchill rode out with a force of 1,000 fighting men, who were divided into three columns to cover as much of the valley as possible in a day. He was attached to the centre column commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Goldney of the 35th Sikhs.

The objective of Goldney’s column was to destroy two villages at the far end of the valley, Badelai and Shahi-Tangi. Seventy-five men from the Sikhs were detached from the main force to take the conical hill between the two villages, while another company of around eighty-five men, including Churchill, were ordered to advance up the long, rocky spur that led to Shahi-Tangi. All of these targets have featured more recently in drone strikes carried out by the US military against Taliban targets in what are now the tribal areas of northern Pakistan.

Having satisfied themselves that the village was deserted, the soldiers set fire to whatever would burn before being ordered to withdraw after fifteen minutes. But in their haste to reach the village, the Sikhs had inadvertently strayed beyond the safety of the cover provided by the mountain guns.

This was just the opportunity the tribesmen thrived upon. The British force suddenly found itself isolated, and the tribesmen gathered to attack. As Churchill and the other soldiers rested from the exertion of their morning climb, they found the eeriness of the deserted village disconcerting. “We are rather in the air here,” remarked one officer.

When Goldney eventually gave the order to retire, the enemy began to collect on all sides, and “thereupon promptly attacked in force, and the Sikhs were driven back about a mile, to the foot of the spur,” as the official account recorded. While Churchill and the Sikhs were fighting their way to safety, another large group of tribesmen moved to cut off their retreat.

Winston and his party suddenly found themselves in a position of the utmost peril. As he later recalled in My Early Life: “Like most young fools, I was looking for trouble, and only hoped that something exciting would happen. It did!”

Certainly an Adventure

The tribesmen had kept themselves well concealed as the Sikhs advanced on Shahi-Tangi, but now attacked the retreating British in force: “Suddenly the mountain-side sprang to life. Swords flashed from behind rocks, bright flags waved here and there. A dozen widely scattered smoke-puffs broke from the rugged face in front of us. Loud explosions resounded close at hand. From high up on the crag, one thousand, two thousand, three thousand feet above us, white or blue figures appeared, dropping down the mountainside from ledge to ledge like monkeys down the branches of a tall tree. A shrill crying rose from many points. Yi! Yi! Yi! Bang! Bang! Bang! The whole hillside began to be spotted with smoke, and tiny figures descended nearer to us.”

The spur along which the British force was retreating consisted of three interconnected knolls. Churchill, another officer, and eight sepoys were left to hold the second knoll and provide cover as the rest of the unit withdrew to the third knoll below. But when the turn came for Churchill’s group to retire, they came under heavy fire from tribesmen who had seized the first knoll vacated by the retreating British.

Churchill, unaware of the impending danger, had spent around five minutes taking what he called “casual pot-shots” at the tribesmen from his protected position at the second knoll. Then, as Churchill’s ten-strong group rose to withdraw to the third knoll, they were met with a well-aimed volley of fire from the tribesmen, which killed two, including Churchill’s fellow officer, and wounded three others.

As Churchill recalled: “The rest of our party got up and turned to retreat. There was a ragged volley from the rocks: shouts, exclamations, and a scream. I thought for a moment that five or six of our men had lain down again. So they had: two killed and three wounded. One man shot through the breast and pouring with blood, another lay on his back kicking and twisting. The British officer was spinning round just behind me, his face a mass of blood, his right eye cut out. Yes, it was certainly an adventure.”

Winston and the other uninjured soldiers desper1ately tried to pull the wounded back to safety, but had no covering fire. As Churchill observed: “It is a point of honour on the Indian frontier not to leave wounded men behind. Death by inches and hideous mutilation are the invariable measure meted out to all who fall in battle into the hands of the Pashtun tribesmen.”

The adjutant of the 35th Sikhs, Lieutenant Victor Hughes, with a number of sepoys, rushed to assist with the recovery of the dead and injured, but was himself shot. Churchill and the other survivors continued to drag and carry the casualties down the hill, passing through a group of deserted houses, with the tribesmen in hot pursuit, firing at the retreating British.

“The bullets passed in the air with a curious sucking noise, like that produced by drawing the air between the lips,” Churchill observed. One of the Sikhs helping to carry the wounded along the spur was shot through the calf, causing him to shout out in pain. “His turban fell off,” Churchill recorded, “and his long black hair streamed over his shoulders—a tragic golliwog.”

Now Churchill and another soldier tried to drag the injured Sikh to safety, but they treated him so roughly, dragging him across sharp rocks, that he pleaded to be allowed to go alone: “He hopped and crawled and staggered and stumbled, but made a good pace. Thus he escaped.”

Churchill reacted with fury when he spotted a group of Pashtuns about to attack the injured adjutant and his rescuers. Four soldiers trying to carry Hughes to safety were attacked by half a dozen Pashtun swordsmen.

The bearers dropped the adjutant and rushed for their lives. Churchill was aghast as “the body sprawled upon the ground. A tall man in dirty white linen pounced down upon it with a curved sword. It was a horrible sight.” Churchill could not bear to see his injured comrade hacked to death by the fanatical tribesman.

As he later wrote: “I forgot everything else at this moment except a desire to kill this man. I wore my long cavalry sword well-sharpened. After all, I had won the Public Schools fencing medal. I resolved on personal combat à l’arme blanche. The savage saw me coming. I was not more than 20 yards away. He picked up a big stone and hurled it at me with his left hand, and then awaited me, brandishing his sword. There were others waiting not far behind him. I changed my mind about the cold steel. I pulled out my revolver, took, as I thought, most careful aim, and fired. No result. I fired again. No result. I fired again. Whether I hit him or not, I cannot tell. At any rate he ran back two or three yards and plumped down behind a rock. The fusillade was continuous. I looked around. I was alone with the enemy. Not a friend was to be seen. I ran as fast as I could. There were bullets everywhere.”

Detecting Emotion

Churchill had demonstrated courage and resolve in the face of a determined enemy—qualities he would display on many more occasions during his long and eventful life. He spent nearly six weeks risking life and limb fighting the Pashtun tribesmen, and on several occasions came close to being killed, or at the very least suffering serious injury. He was involved in what he described as three “sharp skirmishes” and, as he later boasted to his mother, came under fire “10 complete times” and even received a mention in dispatches for his bravery.

One of the more poignant moments of the campaign for Churchill came on 30 September when a close friend, Lieutenant William Browne-Clayton, was killed fighting alongside him. As a young man, Churchill did not believe he was prone to overt displays of emotion, but Browne-Clayton’s death hit him hard. In a letter home a few weeks after the fighting had concluded, Churchill wrote, “I very rarely detect genuine emotion in myself, but I must rank as a rare instance the fact that I cried when I met the Royal West Kents on the 30th Sept. and saw the men really unsteady under fire and tired of the game, and that poor young officer Browne-Clayton, literally cut to pieces on a stretcher.”

Had it not been for Churchill’s own good fortune, he could easily have suffered a similar fate, and the history of the twentieth century may well have taken a very different course.

Con Coughlin is the executive foreign editor for the Daily Telegraph. All quotations in this article are drawn from his book Churchill’s First War: Young Winston at War with the Afghans (Thomas Dunne Books, 2014). On page 39 of this issue of Finest Hour he reviews Churchill Comes of Age: Cuba, 1895, by Hal Klepak.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.