Finest Hour 170

Churchill and Dr. Chaim Weizmann: Scientist, Zionist, and Israeli Statesman

Dr. Chaim Weizmann

December 3, 2015

Finest Hour 170, Fall 2015

Page 11

By Fred Glueckstein

On 9 December 1905, Winston Churchill was given his first government post by Prime Minister Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman as the new Under-Secretary for the Colonies. As then required by law, an MP taking a government position had to contest his parliamentary seat in a by-election. The next day, 10 December 1905, Churchill was electioneering as the key speaker at a Manchester North West public protest meeting on the ill treatment of Jews in Russia.

As a third of the Manchester North West electorate was Jewish, a gathering of Jewish residents was present to hear Churchill speak. On the meeting’s podium when Churchill spoke was a Jewish chemist and Zionist named Dr. Chaim Weizmann.1

With the general election of January 1906 close at hand, Churchill later approached Weizmann through his representative to help swing the Jewish vote in his favour in Manchester. Weizmann, although he recognized Churchill’s authority, was disinclined to intervene so overtly in British politics, and he just referred the matter to David Wolffsohn, President of the Zionist Organization. Shortly afterwards, Weizmann met with Churchill “for a brief, introductory and uneventful talk.”2

Weizmann’s Early Life

Chaim Azriel Weizmann was born in Motol, Russia on 27 November 1874. Three days later, on 30 November 1874, Winston Churchill was born at Blenheim Palace in England.

Knowing that the pursuit of his love of chemistry in Russia was not possible due to the barriers placed before Jews aspiring to higher education, Weizmann left Russia in 1894 and spent the next four years in Germany. He attended Technische Hochschule of Darmstadt and Charlottenburg Technical University at Berlin. When a favorite professor joined the staff of the University of Freiburg in Switzerland, Weizmann went there to study and earn a doctorate in Biochemistry.

While in Switzerland, Weizmann took a position as a lecturer in organic chemistry at the University of Geneva, where he taught and continued his research. In Geneva, Weizmann became active in Zionism, a nationalist and political movement of Jews and Jewish culture that supported the re-establishment of a Jewish homeland in the territory defined as the historic land of Israel.

In 1905, Weizmann went to England and resided in Manchester, where he lectured in the chemistry department at the University of Manchester. In 1910, Weizmann became a naturalized British subject.

“Can You Make It?”

During the First World War, Winston Churchill and Chaim Weizmann again crossed paths in Manchester. As the war intensified, Churchill, as First Lord of the Admiralty, faced an increased shortage of acetone, the solvent used in making cordite, which was the essential naval explosive. The head of the Admiralty’s powder department, a Jewish chemical engineer named Sir Frederick Nathan, suggested that Churchill approach Weizmann at Manchester University. Churchill agreed and Nathan set up a meeting.

In his memoirs, Weizmann remembered their meeting. “Mr. Churchill, then a much younger man, was brisk, fascinating, charming and energetic. Almost his first words were: ‘Well, Dr. Weizmann, we need thirty thousand tons of acetone. Can you make it?’ I was so terrified by this lordly request that I almost turned tail,” wrote Weizmann. But he did answer.

Weizmann told Churchill: “So far I have succeeded in making a few hundred cubic centimeters of acetone at a time by the fermentation process. I do my work in a laboratory. I am not a technician. I am only a research chemist,” said Weizmann.3

Weizmann continued: “But, if I were somehow able to produce a ton of acetone, I would be able to multiply that by any factor you choose. Once the bacteriology of the process is established, it is only a question of brewing. I must get hold of a brewing engineer from one of the big distilleries, and we will set about the preliminary task.” Finally, Weizmann told Churchill: “I shall naturally need the support of the Government to obtain the people, the equipment, the emplacements and the rest of it. I myself can’t even determine what will be required.”4

In May 1915, after Weizmann had demonstrated to Churchill and the Admiralty that he could convert 100 tonnes of grain to twelve tonnes of acetone, the government commandeered brewing and distillery equipment. Factories were built to utilize the new process at Holton Heath in Dorset and King’s Lynn in Norfolk. The factories together produced more than 90,000 gallons of acetone a year, enough to feed the war’s seemingly ravenous demand for cordite. From 1914 to 1918, Churchill’s Royal Navy and the British Army fired 248 million shells.

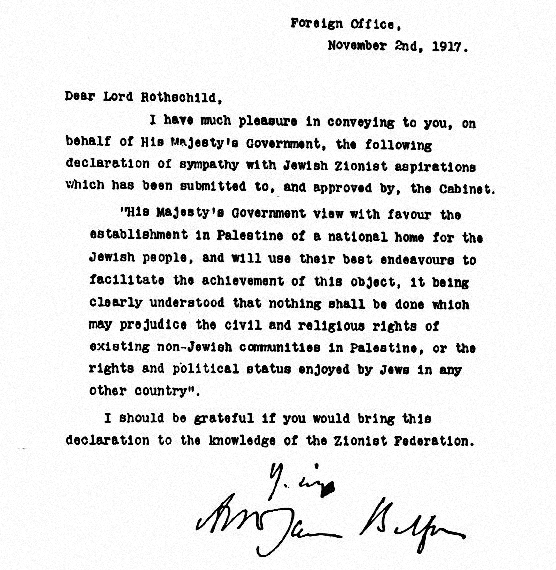

The Balfour Declaration

It is believed Weizmann was rewarded for his vital contribution to Britain’s war effort when the Cabinet, prompted by Prime Minister Lloyd George, approved the signing of the Balfour Declaration on 2 November 1917. Taking the form of a letter from Arthur Balfour, the foreign secretary, to Lord Rothschild, a leader of the British Jewish community, for transmission to the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland, the Balfour Declaration asserted:

His Majesty’s Government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.5

The Balfour Declaration was universally recognized as a personal triumph of Weizmann. In his memoirs, Lloyd George wrote that Weizmann’s name “will rank with that of Nehemiah [responsible for the fifth-century BC rebuilding and restoration of Jerusalem] in the fascinating and inspiring story of the children of Israel.”6 History has recognized that the Balfour Declaration was the first step on the road to Israeli statehood.

Defending the Settlement

Churchill expressed his view of Judaism, the Jews, and their role in history on 8 February 1920 in the Illustrated Sunday Herald: “No thoughtful man can doubt the fact they are the most formidable and the most remarkable race which has ever appeared in the world.”7

Weizmann became president of the World Zionist Organization in 1921. Churchill’s son Randolph remembered Weizmann visiting the Churchill home at Chartwell at the time of the 1930 White Paper discussions. Randolph told Martin Gilbert that his father had been fascinated by Weizmann’s talk and appearance: “Just like an Old Testament prophet,” Churchill told his son when Weizmann had left.8

In 1939, Weizmann travelled from Palestine to England to convince the Government not to publish the proposed White Paper limiting the Balfour Declaration to Palestine west of Jordan, creating an independent Palestine to be governed by Palestinian Arabs and Jews in proportion to their numbers in the population, establishing a limit of 75,000 Jewish immigrants for the five-year period 1940–44 (consisting of a regular yearly quota of 10,000 and a flexible supplementary quota of 25,000). After 1944, the further immigration of Jews to Palestine would depend on permission of the Arab majority. Restrictions were also placed on the rights of Jews to buy land from Arabs.

With the debate on the White Paper approaching in the House of Commons, Weizmann wrote: “Shortly after my return from my brief visit to Palestine, I met Winston Churchill and he told me he would take part in the debate, speaking of course against the proposed White Paper. He suggested that I have lunch with him on the day of the debate….There were present at lunch, besides Churchill and myself, Randolph Churchill and Lord Cherwell….He produced a packet of small cards and read his speech out to us; then he asked me if I had any changes to suggest.

“I answered that the architecture of the speech was so perfect that there were only one or two points I might want to alter—but they were so unimportant that I would not bother him with them. As everyone now knows, Mr. Churchill delivered against the White Paper, one of the great speeches of his career.”9 The Government won a victory on 23 May 1939 by 268 votes to 179.

The Second World War

During the War, Benjy, the oldest son of Chaim and Vera Weizmann, joined an artillery battalion and was stationed in the South of England. Their younger son Michael enlisted in the RAF. Through Weizmann’s efforts, Churchill approved the establishment of the British Army’s Jewish Brigade Group. It was formed in late 1944, and its soldiers fought the Germans in Italy. The brigade was composed of Jews from the Yishuv (Jewish residents in Palestine) and was commanded by Jewish officers who served in Europe.

In early 1942, Weizmann received a call from John Gilbert Winant, the United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom. Subsequently, the men met, and Winant told Weizmann that President Roosevelt had expressed an interest to have him come to the United States to work on the problem of synthetic rubber. The Weizmanns arranged to fly to New York on 13 February. On the 12th they were in Bristol for the night. Early the next morning before leaving for the airport, Weizmann was informed that his son Michael had been posted as missing on the night of the eleventh.

While serving as a pilot in No. 502 Squadron, Michael Weizmann was killed at the age of twenty-five when his plane was shot down over the Bay of Biscay on 11 February 1942. Chaim Weizmann never fully accepted his son’s death, thinking perhaps he had been captured, and he made a provision in his will in case he returned.10

Meanwhile, Churchill and Weizmann developed a close friendship. In a letter from Churchill to Weizmann dated 30 October 1942, he made reference to the forthcoming twenty-fifth anniversary of the Balfour Declaration and the anguish of the Jews wrought by the Nazis. Churchill wrote: “My thoughts are with you on this anniversary. Better days will surely come for your suffering people and for the great cause for which you have fought so bravely. All good wishes.”11

Churchill’s high opinion of Weizmann was in evidence in July 1944. When Weizmann learned early of the horrific gassing of Jews at Auschwitz, he went to the Foreign Office on 6 July with Moshe Shertok, the Jewish Agency official in charge of diplomatic contacts and initiatives, to see Anthony Eden. Eden immediately passed on their news and pressing requests to Churchill. With deportations still taking place in Hungary, Weizmann and Shertok asked the allies to bomb the railway lines leading from Budapest to Auschwitz. Churchill immediately wrote Eden: “Get anything out of the Air Force you can, and invoke me if necessary.”12

The President and the Prime Minister

Before travelling to Palestine in 1944, Weizmann visited Churchill at 10 Downing Street. According to one of Weizmann’s friends, as they shook hands, Churchill said, “You’re looking very young.” Weizmann replied: “I’ll be 70 next month.” Churchill replied: “So will I, but I don’t look it.” But before Weizmann could put forward a suitable response, Churchill exclaimed: “And why, pray, don’t you return the compliment?”13

On 17 February 1949, as the head of the first Jewish state in 2,000 years, Chaim Weizmann was inaugurated as the first President of Israel. Raising his right hand before the recently elected Israeli Parliament that named him President the night before, he said: “I, Chaim Ben Ozer Weizmann, as President of the state, swear allegiance to the state of Israel and its laws.”14

One of the first letters Churchill received after he became Prime Minister for the second time on 26 October 1951 was from Weizmann, who congratulated him on his return to power. Churchill responded: “Thank you so much for your letter and good wishes. The wonderful exertions which Israel is making in these times of difficulty are cheering to an old Zionist like me. I trust you may work with Jordan and the rest of the Moslem world. With true comradeship there will be enough for all. Every good wish my old friend.”15

Worn out by sorrow, strenuous political dissension, and afflicted by frail health and failing sight, Weizmann, nevertheless, maintained a brave appearance in the postwar years. After a long illness, however, Chaim Weizmann died on 9 November 1952.

On the day following Weizmann’s death, during a parliamentary debate on Egypt, Churchill stated: “There is another country I must mention at this moment. Those of us who have been Zionists since the days of the Balfour Declaration know what a heavy loss Israel has sustained in the death of its President, Dr. Chaim Weizmann.

“Here was a man whose fame and fidelity were respected throughout the free world, whose son was killed fighting for us in the late war, and who, it may be rightly claimed, led his people into their promised land, where we have seen them invincibly established as a free and sovereign State,” said Churchill.16

“A Man of Vision and Genius”

In the years that followed, Churchill remembered Weizmann’s friendship and the role he played in the creation of Israel. In March 1954, the Manchester Zionist Council organized an exhibition titled “Manchester and Israel: a city’s contribution to the birth of a state.” The exhibition coincided with the fiftieth anniversary of Weizmann’s arrival in Manchester.

“The city of Manchester may be proud,” wrote Churchill, “of its connection with Dr. Weizmann, a man of vision and genius, whose lasting memorial will be the vigour and the prosperity of the State of Israel, which he did more than any other single man to inspire and create. I am indeed glad that Manchester should commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of this great man’s arrival in our country. And I send my best wishes for the success of the exhibition which is being held.”17

Churchill admired Chaim Weizmann as a scientist, as a Zionist, and as a statesman. Weizmann had a high regard for the British statesman, particularly for his early support of Zionism, as a war-time leader, and as a supporter of Israel. After their initial meeting in 1905 at the protest assembly in Manchester, they eventually developed a friendship that lasted almost fifty years. During that time, Churchill and Weizmann each established his place in their countries’ histories.

Fred Glueckstein is a frequent contributor to Finest Hour and the author of Churchill and Colonist II, reviewed on page 43.

Endnotes

1. Martin Gilbert, Churchill and the Jews (London: Simon & Schuster, 2007), p. 11.

2. Norman Rose, Chaim Weizmann: A Biography (New York: Viking, 1986), p. 100.

3. Gilbert, Churchill and the Jews, p. 24.

4. Ibid.

5. Jonathan Schneer, The Balfour Declaration: The Origins of the Arab-Israeli Conflict (New York: Random House, 2010), p. 341.

6. Robert Fisk, The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), p. 366.

7. “Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill,” Encyclopedia Judaica (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1971), p. 555.

8. Gilbert, Churchill and the Jews, p. 95.

9. Chaim Weizmann, Trial and Error: The Autobiography of Chaim Weizmann, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1949), vol. II, pp. 411–12.

10. Chaim Weizmann. Wikipedia.

11. Martin Gilbert, The Churchill Documents, Volume 17, Testing Times, 1942 (Michigan: Hillsdale College Press, 2014), p. 1327.

12. Gilbert, Churchill and the Jews, p. 212. Three days after Churchill endorsed the bombing of the railway lines leading from Hungary to Auschwitz, the deportation of Jews from Hungary to Auschwitz was halted by the Hungarian Regent, Admiral Horthy. His decision to halt the deportations was due to the American daylight bombing on Budapest on 2 July 1944 that was part of the plan to bomb regularly German fuel depots and railway marshalling yards.

13. Julian Louis Meltzer, “Weizmann Views Palestine’s Needs,” The New York Times, 27 November 1944, p. 15.

14. “Chaim Weizmann Installed as Israel’s First President,” The New York Times, 18 February 1949, p. 14.

15. Gilbert, Churchill and the Jews, p. 282.

16. Ibid., p. 283.

17. Ibid., pp. 289–90.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.