Finest Hour 170

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – In the Lands of the Prophet

December 3, 2015

Finest Hour 170, Fall 2015

Page 36

Review by Ashley Jackson

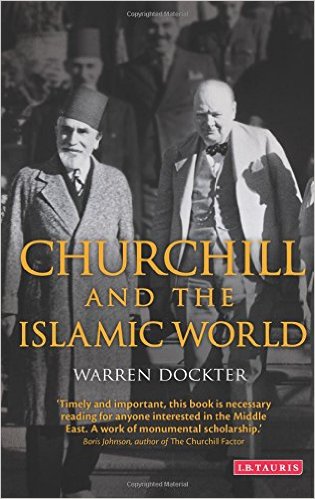

Warren Dockter, Churchill and the Islamic World, I. B. Tauris, 2014, 288 pages, £25.00 / $40.00.

ISBN 978-1780768182

A century ago Western politicians, as this book makes clear, were as clueless about Islamic culture and politics as they are today. But then as now that did not prevent Westerners from making airy pronouncements about the Islamic world or relieve their leaders of the need or temptation to formulate policies towards Islamic societies and initiate actions within them. Even a man such as Winston Churchill, who evinced a consistent interest in Islam and could bring to bear his intense intelligence, simply did not have a deep or objective enough knowledge to appear, in retrospect, well informed.

A century ago Western politicians, as this book makes clear, were as clueless about Islamic culture and politics as they are today. But then as now that did not prevent Westerners from making airy pronouncements about the Islamic world or relieve their leaders of the need or temptation to formulate policies towards Islamic societies and initiate actions within them. Even a man such as Winston Churchill, who evinced a consistent interest in Islam and could bring to bear his intense intelligence, simply did not have a deep or objective enough knowledge to appear, in retrospect, well informed.

Finest Hour readers will be aware of the extent of Churchill’s association with the “Islamic world,” and the manner in which it presented itself to a politician of the period. The Ottoman Empire regularly intersected British imperial and foreign policy and influenced public awareness of the fault lines between east and west, Islam and Christianity. Further, the British Empire’s position as a “Muslim power” was never far from the thoughts of statesmen. Churchill experienced fighting on India’s North-West Frontier and was influenced by figures such as Wilfrid Scawen Blunt and T. E. Lawrence. He engaged with Islamic regions during stints at the Air Ministry, Colonial Office, and War Office, and was instrumental in determining the political contours of the Middle East following the Great War. Later came his engagement with political reform in India and the position of the subcontinent’s Muslim population, and the travails of British policy in Palestine.

Warren Dockter’s meticulously researched study is a welcome addition to the procession of Churchill and… titles. It gainfully corrals information regarding Islamic people and regions scattered across a long and helter-skelter life of action, thinking, and writing, and makes analytical sense of it all. This approach is a profitable way of “data-mining” Churchill’s biography, discovering what influenced him, and how in turn he influenced and acted upon events. It also allows Dockter to cast a powerful beam on important aspects of Churchill’s career and thinking. This illumination sharpens the picture and aids its interpretation, even if experts will already know—or at least have an intuitive sense—of what is there to be found.

By examining Churchill’s entire career, Dockter offers a nuanced understanding of Churchill’s attitudes towards Islamic people, their culture and politics. Understandably, the story of Churchill and the “Islamic world” (itself, a vague and problematic appellation) is one of “ever-changing ideas, attitudes, and policies.” Because his attitudes were “multi-dimensional and highly complex,” profound revelations about Churchill’s attitudes and what motivated his actions, and the discovery of an interpretative golden thread, is beyond this study. This is no fault of the author’s, because these things are not there to be found in the first place.

Churchill’s attitudes were influenced by his mercurial enthusiasm as well as his humanity, perceptiveness, focused intelligence, judgement, and magnanimity. Nevertheless, his core beliefs in the beneficence of the British Empire, British superiority, and the need to act in the interests of his country skewed things considerably. Sometimes, principle and intellectual logic were compromised by the imperatives of political expediency. So while seeking to suggest that Churchill had a deeper understanding of, and “camaraderie” with, the Islamic world, Dockter cannot overcome the constraints his subject imposes upon him.

It is impossible to escape the fact that Churchill was over-confident in his knowledge and complacent when pronouncing on lofty issues (such as world religions) and the intimate affairs of people whom he had never met, studied, or understood. As Dockter is happy to state, “Churchill’s fascination with Islam proved only to be aesthetic and passing. His knowledge of Islam was largely predicated on Victorian notions [as in many other studies, the ‘Victorian’ cliché for Churchill and his ideas is unhelpful, given that the attitudes so described remained powerful and indeed commonplace deep into the twentieth century], which heavily romanticized the lifestyle and honour culture of the Bedouin desert tribes. As a result, Churchill never really acquired a deeper understanding of Islam.”

Given this, only so much renovation is possible, especially considering the chasm that separates acceptable political and cultural ideas then and now. While it is true that Churchill “shared many Victorian prejudices such as the belief that British culture was inherently superior to Eastern cultures…his experience of the Islamic world informed his opinions and differentiated him from many politicians of the day.” But the racial prejudices and assumptions cannot be expunged, and Dockter makes no attempt to do so. Neither can the effects of the prevailing beliefs in the British Empire as a civilizing force and the British as legitimate rulers and arbiters of the affairs of others.

Churchill’s attitudes and actions were paradoxical and complex, but they could not really have been anything else. He was a product of his own background and time, as Dockter avers; Churchill’s ideals and policies were filtered through the needs of his country, as he perceived them. Perhaps Churchill’s most fundamental interest in Islam was the extent to which Muslims might help or hinder the interests of the British Empire.

In many ways, Churchill’s antique views are of little relevance to today’s world, though some will naturally seek to cast a book such as this as a “must read” for those wanting to gain extra insight into (say) the modern Middle East and the West’s engagement with Islam and Muslim populations. What this study does, admirably, is to place under the microscope Churchill’s attitudes on a fascinating subject, and enrich our appreciation of what motivated him, thereby better explaining his thoughts and actions.

Ashley Jackson is Professor of Imperial and Military History at King’s College, Lon- don, and author of the biography Churchill, published by Quercus in 2011.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.