Finest Hour 170

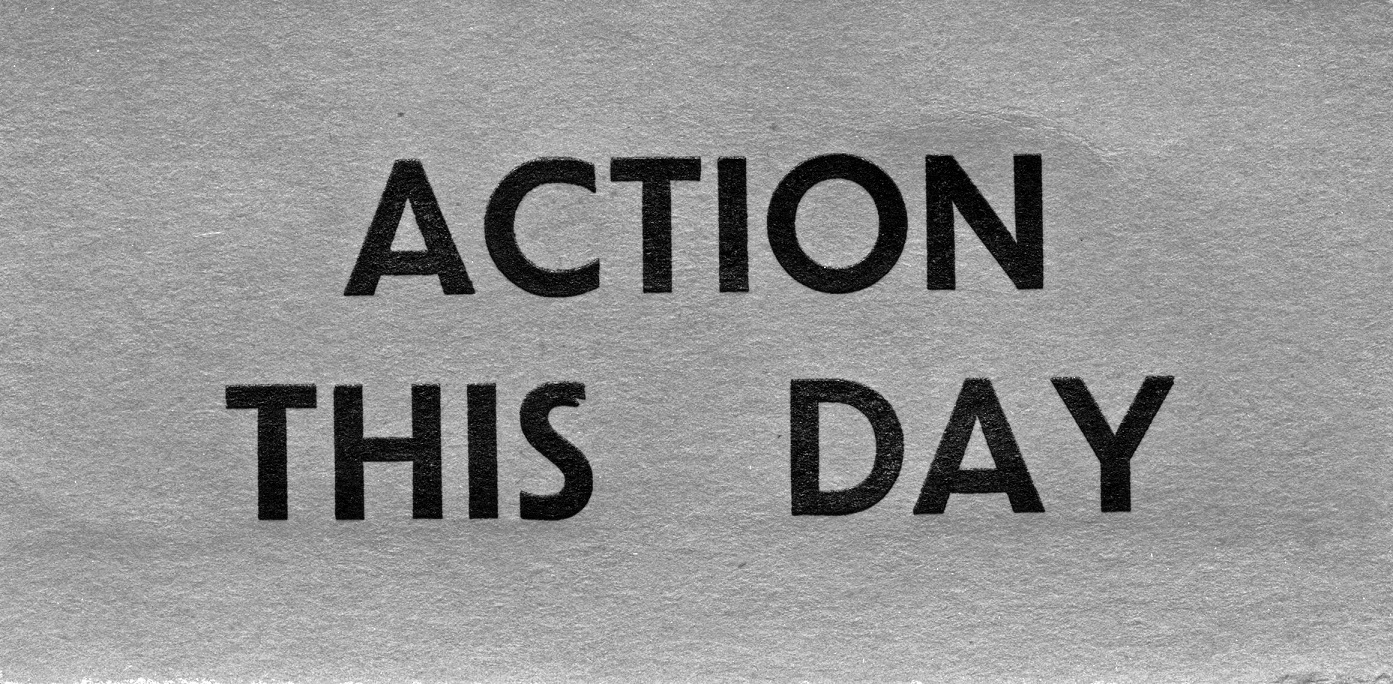

Action This Day – Spring 1890, 1915, 1940

December 3, 2015

Finest Hour 170, Fall 2015

Page 34

By Michael McMenamin

125 Years ago

Spring 1890 • Age 16

“I am working my very best”

In December 1890, Winston was set to take the Preliminary Examination for Sandhurst. In the days leading up to the exam, however, he told his mother that he thought he would not pass because he had been put under a master “whom I hated & who returned that hate.” Lady Randolph was not pleased, and her displeasure made its way to her son. In mid-November, Winston wrote and reassured her that he had complained to the headmaster about the hated master, who had since been replaced “by masters who take the greatest interest in me & who say that I have been working very well.” “Arithmetic & Algebra are the dangerous subjects,” Winston continued, but he was “sure of English” and “nearly sure of Geography, Euclid & French.” He concluded his letter asking her to take his “word of honour…that I am working my very best.”

Apparently Lady Randolph did not do so and visited Harrow herself to talk to Harrow’s Headmaster James Welldon, who backed up Winston’s claim. She wrote to her husband on 23 November explaining that “Winston was working under a master he hated—& that one day the master accused him of a lie—whereupon Winston grandly said that his word had never been doubted before & that he wld go straight to Welldon—which he did.” She explained further that Welldon had sided with Winston and placed him with a new master and that Welldon “thought Winston was working as hard as he possibly cld & that he would pass his preliminary exam.”

In the event, Winston did pass his preliminary exam in all subjects including the “dangerous” mathematics, something accomplished by only twelve of the twenty-nine students who took the exam.

100 Years ago

Spring 1915 • Age 41

“Asquith will throw anyone to the wolves”

From his position on the Dardanelles Committee, Churchill continued to write memoranda and letters on war policy. He optimistically wrote to his brother Jack on 2 October that “I am slowly gathering strength & influence in council in spite of” the Dardanelles. His optimism proved to be premature.

On 5 October, Churchill wrote to Asquith outlining four possible attacks against Bulgaria in the Balkans if it invaded Serbia and suggesting the War Office examine them. On 6 October, he wrote to Asquith proposing that a special sub-committee of the Dardanelles Committee be established to examine the future of the Gallipoli campaign and report to the War Council because Lord “Kitchener [the War Secretary] is far too busy” to do so. Churchill proposed that he and Lloyd George be appointed to the special sub-committee because he was known as an advocate of continuing the Gallipoli campaign whereas Lloyd George was in favor of evacuating troops from the peninsula.

Nothing came of Churchill’s proposals, and, in late October, Asquith announced his intent to disband the Dardanelles Committee and replace it with a three-man war policy committee consisting of himself, Kitchener, and Arthur Balfour, the First Lord of the Admiralty. Churchill, therefore, would have no direct input into war policy, and on 30 October he tendered his resignation from the Cabinet.

Asquith persuaded Churchill to defer his resignation for a few days, as he intended to make a statement in the House on 2 November that he said would include a full explanation of the Dardanelles. Thinking the Prime Minister intended to defend him from what Churchill believed were unfair and unfounded charges, he agreed and prepared a statement for Asquith to deliver on the Dardanelles. In the event, Asquith defended the Dardanelles in only general terms and defended Churchill’s role not at all.

Thereafter, Asquith finally gave in to the Cabinet’s growing discontent with Kitchener. Instead of a three-man war policy committee including Kitchener, the Prime Minister created a new five-person war committee on 11 November that did not include Kitchener or Churchill. That same day, Churchill resubmitted his resignation and Asquith accepted.

Earlier, on 6 November, Churchill had asked Asquith to make him Governor-General of British East Africa and Commander-in-Chief of British forces there, who were then fighting the Germans. On 12 November, Churchill’s old nemesis, Conservative leader Andrew Bonar Law, now a member of the new War Committee, wrote to Asquith endorsing Churchill’s appointment. Despite this, Asquith still denied Churchill the appointment.

In late November, a decision was made to evacuate troops from the Gallipoli Peninsula, a decision that Cabinet Secretary Maurice Hankey characterized as “an entirely wrong one” in his diary. “Since Churchill left the Cabinet and War Council,” Hankey went on to write, “we have lacked courage more than ever.”

Churchill went to France with the intention of taking up a position in the army. The British Commander-in-Chief, Sir John French, offered Churchill command of a brigade with the rank of Brigadier-General. Asquith, however, vetoed the idea when he learned of it. Later, when French himself was relieved of command, Churchill wrote to his wife, “Asquith will throw anyone to the wolves to keep himself in office.”

75 Years ago

Spring 1940 • Age 66

“We are waiting….So are the fishes”

During the first week in October, 2,000 people were killed in German bombing raids following 7,000 killed the previous month. When the Chief of the Air Staff reported to the War Cabinet that he had ordered a raid on Berlin using 100 bombers and an attack on German barges in the Channel ports using fifty bombers, Churchill told his Private Secretary John Colville, “Let ’em have it. Remember this. Never maltreat the enemy by halves. Once the battle is joined, let ’em have it.”

By attacking London and other large cities, however, Churchill believed Hitler had miscalculated. As he wrote to Neville Chamberlain on 20 October, “The Germans have made a terrible mistake in concentrating on London to the relief of our factories, and in trying to intimidate a people whom they have only infuriated.” When MPs pressed him to retaliate in kind on Berlin, Churchill declined, saying, “This is a military war and not a civilian war. You and others may desire to kill women and children. We desire…to destroy German military objectives. I quite appreciate your point. But my motto is ‘Business before Pleasure.’”

Early in autumn, it was still not clear that Hitler had abandoned plans to invade England. On 22 September, President Roosevelt warned Churchill that Germany would invade that day but corrected this the next day to say it was French Indo-China that was to be invaded by Japan, not England by Germany. On 21 October, Churchill delivered a radio broadcast to France where he referred to the possibility of a German invasion, “We are waiting for the long-promised invasion. So are the fishes.” Later that month and early in November, Enigma intercepts indicated that German invasion plans had been indefinitely postponed.

On 9 October, Churchill agreed, over his wife’s objections, to become leader of the Conservative Party. In his speech of acceptance, however, he emphasized his view that “Empire and liberty” were the sources of British strength and that “all political parties— Conservative, Liberal, Labour—all have borne a part.”

That Churchill retained the confidence of other parties after becoming the Conservative leader is reflected in a diary entry of Labour MP Harold Nicolson on 5 November after Churchill had given a speech on the war situation: “He is rather grim. He brings home to the House as never before the gravity of our shipping losses…it has a good effect. By putting the grim side foremost he impresses us with his ability to face the worst…. If Chamberlain had spoken glum words such as these, the impression would have been one of despair and lack of confidence. Churchill can say them and we all feel ‘Thank God that we have a man like that!’ I have never admired him more.”

A welcome naval victory came on 11 November, the first since Churchill had taken office in May. British naval air forces attacked the Italian fleet at anchor in Taranto and sank three of Italy’s six battleships with torpedoes, a foreshadowing of the equally successful Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor a little over a year later. Churchill sent an account of the attack to FDR and advised taking precautionary steps at Pearl Harbor, e.g., torpedo nets. This was not done because Pearl Harbor, with only a thirty-foot depth, was thought too shallow for use of aerial torpedoes, which convention held needed seventy-five feet of water to be launched successfully. Despite having broken Japanese naval codes, the US Navy never learned that the Japanese had developed shallow-draft torpedoes with which their pilots practiced for six months prior to Pearl Harbor.

The Taranto victory was followed by another a month later in North Africa, where a British offensive effectively drove the Italian Army out of Egypt. More than 7,000 Italians were taken prisoner, including three generals. After this victory, Churchill sent a telegram to South African General Jan Smuts in which he said, “One has a growing feeling that wickedness is not going to reign.”

During this period when victory was far from certain, General Ismay sought to console Churchill that, “whatever the future held, nothing could rob him of the credit of having inspired the country by his speeches.” Churchill, to Ismay’s surprise, denied this was so. Foreshadowing his “lion’s roar” observation after the war, Churchill told Ismay that he had only expressed “what was in the hearts of the British people.”

In reaction to this, Ismay wrote, “I had never attributed to him the quality of humility, and it struck me as odd that he failed to realize the upsurge of the national spirit was largely his own creation. The great qualities of the British race had seemed almost dormant until he had aroused them. They put their trust in him.”

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.