Finest Hour 169

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – Say “No” to Bad History

November 10, 2015

Finest Hour 169, Summer 2015

Page 38

Review by Lee Pollock

Lee Pollock is Executive Director of The Churchill Centre.

Churchill: When Britain Said No

Susan Jones and Nicholas Kent,

Executive Producers

Christopher Spencer,

Producer and Director

Produced by Oxford Film and BBC2, first aired 25 May 2015

2025 International Churchill Conference

Scene from the BBC’s “When Britain Said No”The fiftieth anniversary earlier this year of the death of Winston Churchill produced an international wave of commemoration and a panoply of articles, books, conferences, and programs. Churchill remains among the most widely admired—and most regularly quoted—political figures of the past century.

Scene from the BBC’s “When Britain Said No”The fiftieth anniversary earlier this year of the death of Winston Churchill produced an international wave of commemoration and a panoply of articles, books, conferences, and programs. Churchill remains among the most widely admired—and most regularly quoted—political figures of the past century.

While Churchill’s role in history will be legitimately analyzed for centuries, there is a class of Churchill-bashers (more politely “revisionists”) for whom the adulation of the last few months (and decades) cannot pass without a spirited answer. And where better to do this than on Britain’s state-owned broadcast network, the BBC?

The revisionists’ first salvo was a small blast in January. Jeremy Paxman’s otherwise fine program about the state funeral in 1965, Churchill: The Nation’s Farewell [reviewed in FH 167], made the nonsensical allegation that all dockworkers hated Churchill.

But the BBC saved the heavy artillery for the spring, when it examined Churchill’s election defeat in 1945 in Churchill: When Britain Said No. One can almost hear the voice of John Reith (the Beeb’s long-time, dictatorial Director-General and Churchill’s nemesis) saying, “I did my best to keep him off the air and now you’ve gone one better.”

With programs such as this, the BBC, once a source of admiration for Britain around the world, now seems more of an embarrassment. When Britain Said No belongs in the dustbin of history along with the nationalized industry that the Labour party introduced when it defeated Churchill in 1945.

The 1945 election results remain a puzzle, especially to American admirers of Churchill who, not appreciating Britain’s domestic politics, reacted (and still do) with “How-could-they?” shock.

When Britain Said No purports to explain the result and is described as containing “surprising revelations” (in reality, rehashing already widely-known Churchill controversies) and debating his “weaknesses as well as strengths.” Alas, while the actors are good (portraying Churchill is tricky), and the vintage film footage interesting, it does little of the sort.

In describing his own memoirs of the Second World War, Churchill admitted, “This is not history. It is my case.” But this program is no history either. Rather, to use the invective launched at Churchill by Evelyn Waugh, it is “a shifty barrister’s case.”

When Britain Said No is so one-sided and hysterical that it actually does a disservice to the revisionist cause. It certainly never utters a balancing word or phrase such as “even though” or “but.”

The program trots out so many Churchill clichés and selective, out-of-context quotes that a general viewer would easily be convinced that this most-admired Briton was a racist buffoon. And it picks easy targets.

Yes, Churchill was largely wrong about India, but, if nothing else, Churchill’s warnings about internecine violence in India after partition proved sadly true. Certainly his famous “half-naked Fakir” comment about Gandhi (like Churchill the subject of adulation years after death) haunted him since he made it in 1931. Yet the program fails to note that just a few years later Churchill also said:

Mr. Gandhi has gone very high in my esteem since he stood up for the Untouchables. I do not like the India Bill but it is now on the Statute Book…[so] make the thing a success. I did not meet Mr. Gandhi when he was in England but I should like to meet him now.

To which Gandhi remarked:

I have got a good recollection of Mr. Churchill when he was in the Colonial Office and… since then I have held the opinion that I can always rely on his sympathy and goodwill.

And how does Churchill’s “hatred” of Indians explain his later good relationship with Nehru?

Of course the “Gestapo” comment in the 1945 campaign speech was foolish and ill-advised. His wife Clementine told him so beforehand, and Churchill surely regretted it afterward—and paid the political price.

The program’s litany of other “revelations” about Churchill includes:

• “His policies as Chancellor had led to a disastrous economic collapse.” So he created the Great Depression all by himself? (Hardly, even if the 1925 return by Britain to the Gold Standard—widely-held conventional wisdom at the time—was seriously flawed.)

• He was a stubborn, difficult, and demanding boss. Long known, but one might wonder how well an easygoing and accommodating one would have served Britain in those challenging days. (“I never worry about action, only about inaction” seems a good mantra for fighting a war.)

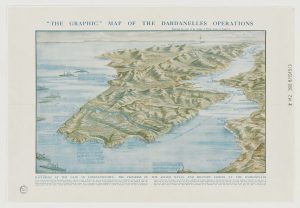

As First Lord of the Admiralty, Gallipoli was Churchill’s “master plan” and thus entirely his responsibility. Not a word is uttered about anyone else. The truth is that there is more than enough blame in the Gallipoli campaign to spread among several people.

Ironically, the program misses a few easy targets. For example, why not trot out Churchill’s 1920 article about Jews and Bolshevism and the one by a ghostwriter, Marshall Diston, from 1937 to prove he was anti-Semitic?

And surely Churchill must have been a secret communist sympathizer—just look at all the nice things he said about Stalin from 1941 to 1945.

The experts interviewed in the program (Sir Max Hastings and Anthony Beevor in particular) are well-regarded historians, although better known for their military than their political writing. But one largely unfamiliar name appears frequently, a Mr. Dave Douglass. While the program skips over his credentials, it turns out he is in his own words “a revolutionary Marxist on the Anarchist left.”

Mr. Douglass apparently worked in the coal industry some decades ago but hardly qualifies as having an objective opinion or, more importantly, any real knowledge about Churchill. He is a strange choice.

A more predictable presence is Prof. John Charmley, the revisionist dean. While Charmley is a successful historian, he seems to have gone off the deep end when the cameras rolled for this program. From Prof. Charmley’s barely suppressed smirk, we learn that Churchill was really a proto-fascist, “the equivalent of Nigel Farrage,” and one step away from throwing in with Oswald Moseley and the Black Shirts.

According to Charmley, “Churchill’s ideas in the 1930s had been rather sympathetic towards fascism; at least until 1938 he’d said obliging things about Hitler as well.” A single line from a 1937 Evening Standard article by Churchill is brought forward to prove the point.

Well, if Churchill was a Nazi sympathizer that certainly was not apparent to Goebbels or Hitler. Prof. Charmley knows very well that a quick glance at the work of Churchill authorities such as Sir Martin Gilbert and Richard Langworth would put this nonsense to rest.

And Charmley cannot resist a last jest, informing us that in Churchill’s war memoirs, “every page…broke the Official Secrets Act,” thus apparently throwing Churchill in with Burgess, McLean, and the other British spies of the 1940s.

The first fifty-five minutes of the program work hard to dig the Churchill reputation a deep grave. The producers then apparently looked up and found themselves at the bottom of a discreditable hole of their own making.

What to do? Why, furiously spend the last five minutes reminding us, “Oh, by the way Winston Churchill was a great man and saved the world.” Even Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke said so.

When Britain Said No concludes with a screen shot, surely confusing to anyone who has just watched the program:

In 1951 Churchill stood again for election— and won.

Which he did, even though (as the program surprisingly fails to note) Labour received some 250,000 more votes than the combined opposition. The viewer might wonder: how could that be? The program offers no answer, and one is left to conclude that either Churchill was not so bad or that the British people having unwisely tossed out the Great Man in 1945 regained their senses and voted him back.

American conservatives often lament the perceived liberal bias of the Public Broadcasting System in the United States. But no PBS station would ever run a program about an American leader as unbalanced and inaccurate as this. The future response to critics of PBS may be, “It could be worse—look at the BBC.”

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.