Finest Hour 168

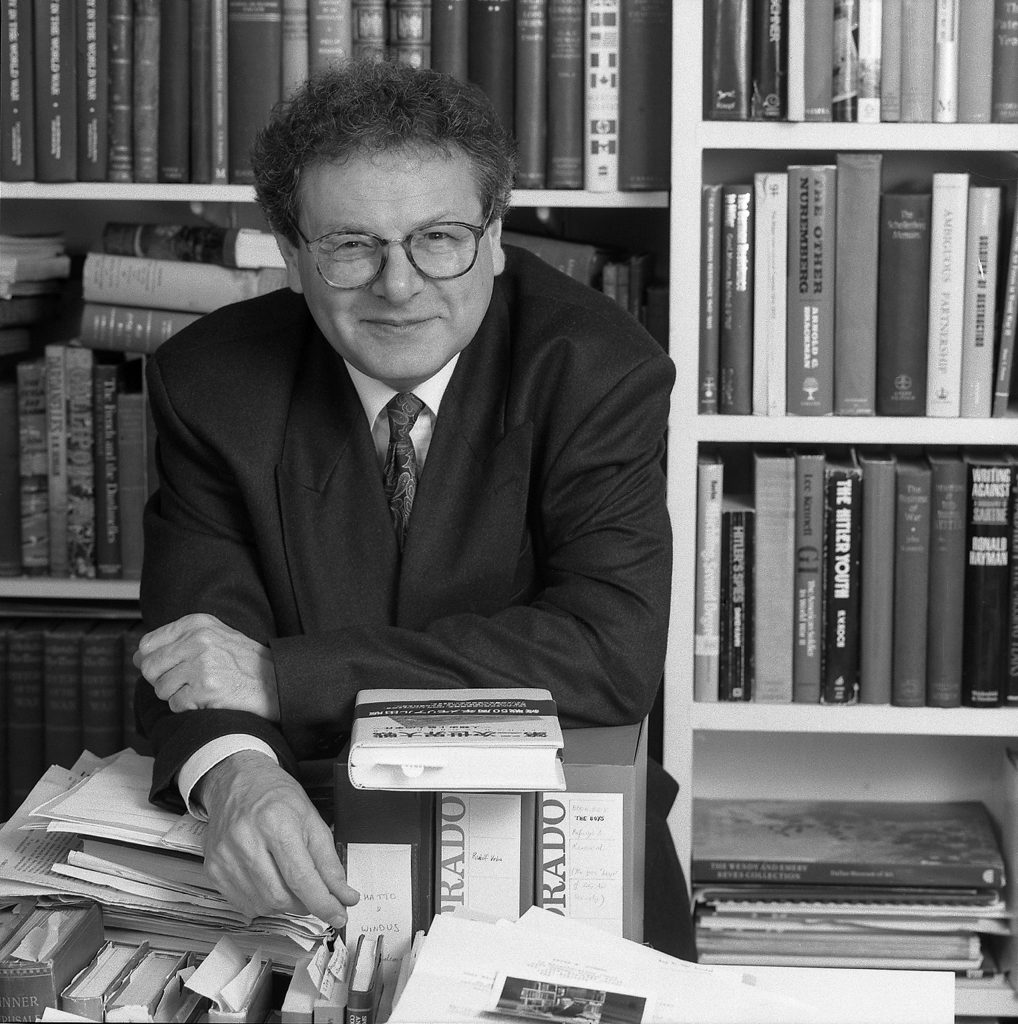

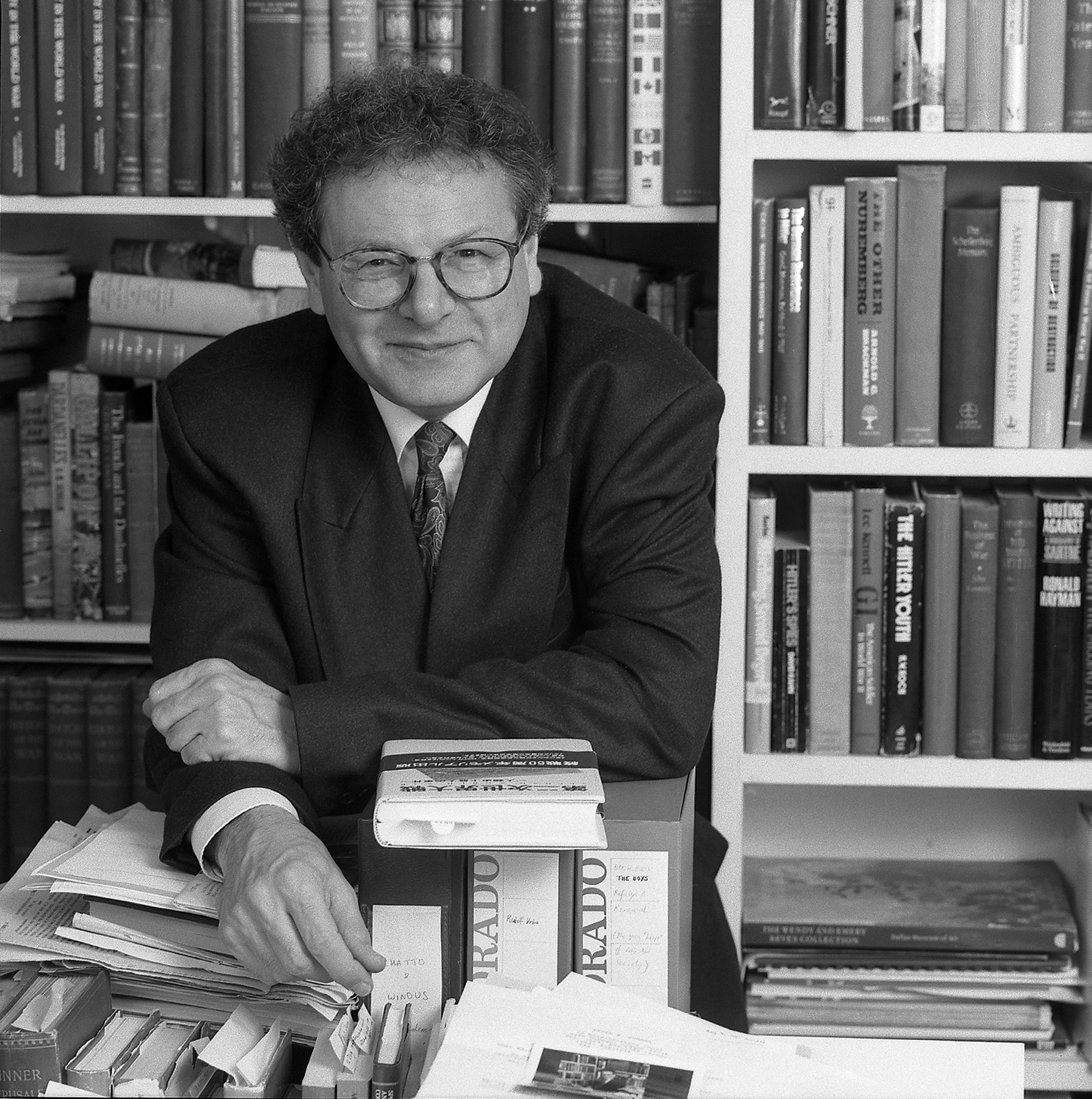

Sir Martin Gilbert: In His Own Words

September 6, 2015

Finest Hour 168, Spring 2015

Page 34

The Churchill Centre’s great friend and honorary member the Rt. Hon. Sir Martin Gilbert passed away on 3 February at the age of 78. Fittingly, he was buried in the British section of the Beit Shemesh cemetery in Israel just west of Jerusalem.

The Autumn 2014 issue of Finest Hour contained tributes to Sir Martin from his many friends and admirers, which his wife Esther was able to share with him before his death. He was both a great historian and a great humanitarian. Thus we leave the final word to the man himself.

I was born in London in October 1936. As my working life has been that of a historian, it is natural for me to look back over my life in historical terms.

I was born in London in October 1936. As my working life has been that of a historian, it is natural for me to look back over my life in historical terms.

The Second World War broke out when I was two-and-a-half years old. Nine months later, as Britain faced a German invasion, I was evacuated to Canada. I have vivid memories of the transatlantic crossing, from Liverpool to Quebec, although I was not yet four years old.

It was in Canada that I learned to read and write. Then, when I was seven-and-a-half years old, and while the war was still being fought, I was brought back to Britain on board the ocean liner Mauretania, then a troopship with mostly American troops on board.

I was in Britain, living just outside Oxford, when Germany surrendered on 8 May 1945. That day I joined a large crowd on the nearest hill where we built a huge bonfire and set alight a straw Hitler and a straw Mussolini.

From 1945 to 1955 I was at a boarding school in London, Highgate School. Two history teachers there, Tommy Fox and Alan Palmer, encouraged me to learn history—and to write it. Several of the teachers had fought in the First World War, including the headmaster, Geoffrey Bell. From these masters came my interest in the First World War—an interest that was to lead me to make many visits to the battlefields of the Western Front, to war cemeteries, and to monuments and memorials throughout Britain and Europe, the Gallipoli peninsula, and the Middle East.

In 1955 I left school. After a mere two weeks footloose and fancy free in London indulging in the theatre, including the Old Vic to see Richard Burton and Claire Bloom in Hamlet, I began the compulsory two years National Military Service.

I left the army in the spring of 1957 and travelled to the Balkans and Turkey, in both of which I taught English. That October I went to Oxford University, where I studied history at Magdalen College. My teachers included the often acerbic but always challenging A.J.P. Taylor, who was then writing his history of the origins of the Second World War.

In the summer of 1959, while still at Oxford as an undergraduate, I went to Poland, which was then behind the Iron Curtain. This Polish visit—the first of many—had two major repercussions on my future research and writing.

First, I travelled to Poland with another undergraduate, Richard Gott, who became my first pupil after I graduated. He and I were to co-author my first book (“our” book), The Appeasers (1963), about British policy before the Second World War, especially towards Czechoslovakia and Poland. Our documented criticism of Neville Chamberlain and the policy of appeasement provoked considerable comment and even controversy when the book was first published.

The second repercussion of my 1959 Polish visit was a growing interest in the Holocaust. This led to eight books in all, researched and written over the next forty-three years.

During the course of my researches I would leave England at least once a year on my travels, mostly to Europe. Becoming aware of the impact and range of the geography of wartime Europe led to my publishing an atlas of the Holocaust. I researched the many facts and details for this atlas not only in Europe itself—I made three further visits to Poland in 1968, 1980, and 1981—but also during a sustained visit to Israel in 1979. The archive at the Holocaust museum, Yad Vashem, in Jerusalem, provided an important source. Several of the scholars there gave me invaluable guidance. No historian can work in a vacuum—or alone in an ivory tower.

After graduating in 1960 with a BA in modern history, I went as a Research Scholar to St Antony’s College, Oxford. In 1961 I was elected a Junior Research Fellow at Merton College, Oxford, which became my academic home and research base for almost twenty years. A year after my election—in tandem with my Oxford position—Churchill’s son Randolph asked me to join his research team on the life of his father, which he had just begun to write. I began work the junior on a team of five. For the next six years I would live at Oxford, and teach and write at Merton College, but be prepared to travel across country to work in the Churchill archive whenever Randolph summoned me.

Randolph Churchill taught me many aspects of the historian’s craft. He was a hard taskmaster but a generous one. Discoveries in archives located far from the Churchill papers were greeted by his enthusiasm. He also encouraged me to go on with my own independent research and writing.

While working for Randolph, making use of my time in Oxford, I also edited the letters, speeches and correspondence of a First World War pacifist, who had gone to prison rather than fight. His name was Clifford Allen. Later, as Lord Allen of Hurtwood, he was active in the appeasement debate. His wife Marjorie, whose own career had included much pioneering work for legislation to protect children, gave me full access to his voluminous correspondence. I called the book, after a phrase that Clifford Allen had used in one of his letters describing his lonely position in public life, Plough My Own Furrow (1965).

A seminar that I gave at Oxford in 1965 led me to publish The Roots of Appeasement (1966). In it I included, as appendices, several previously unpublished documents. Also, to help my students, I had been drawing sketch maps of historical events, changing borders, and the conflicts of the European powers, as well as their imperial activities. This became my first published atlas, The Recent History Atlas (1966).

In 1965 I took a four-month sabbatical from my Oxford and Churchill work to be a visiting Professor to the University of South Carolina. While I was there, Churchill died, and, with Randolph’s approval, I wrote a short, single-volume life of Churchill for Oxford University Press. Randolph read my book in proof, an unnerving experience for me, to have a son read what I had written about his father. But he was full of encouragement. This book is called Winston Churchill (1966), and was my first book about Britain’s war leader.

I also edited a book showing Churchill both from his own words, and the words of his contemporaries. This book (1967) was for an American series called Great Lives Observed. It was followed [in 1968.] by a second volume about Lloyd George. I would have edited a third volume in the series, on Mahatma Gandhi, but in1968 Randolph died.

Following Randolph Churchill’s death, I was asked to take over his task and to complete the Churchill biography—both the main and the document volumes. The Churchill archive was brought to Oxford for my use, and housed in the deepest underground floor of the Bodleian Library. With that treasure trove as my base, I travelled to public and private archives throughout Britain. I also corresponded with many hundreds of Churchill’s contemporaries, and came to know a good number of them as friends. Their recollections, and the archival material which they possessed, became an integral part of my Churchill work.

My own first volume after Randolph’s death, and the third volume of the biography, was published in 1971, The Challenge of War, 1914–1916. It was followed a year later by a two-volume set of documents, known as Companion Volumes to the biography.

These “companion volumes” of documents contained a wealth of personal and official correspondence, written by Churchill, and sent to him, as well as transcripts of the many secret meetings at which policy was worked out, including that of the ill-fated attack on the Dardanelles and the subsequent Gallipoli landings. I also published all his private letters from the trenches of the Western Front, where he served during the first five months of 1916: letters to his wife, to his mother, to his close friends, and to his former political colleagues, whom he was desperate to rejoin.

While teaching at Oxford and working for Randolph, I had published Britain and Germany Between the Wars (1964), an edition of documents with commentary. In it, I included some letters and documents from Sir Horace Rumbold, the British ambassador in Berlin when Hitler came to power. I was so struck by the vivid quality of Rumbold’s reports that I went to see his son’s collection of family papers. The result was a full-length biography published in 1973. It is one of the books of which I am most proud.

Later that year I was about to embark on the Middle East research for the fourth volume of the Churchill biography and was visiting Israel, when war broke out there: the Yom Kippur War, also known as the October War. I have never published my experiences of that time, although I did keep a detailed diary. One day, perhaps, I will publish it. [Alas, he did not— Ed.]

While working in the archives on the Churchill biography, I came across many more photographs than I could use in the volumes themselves. I visited a number of photographic archives in London, and found that they were then in the process, inconceivable thirty years later, of weeding out and destroying tens of thousands of photographs, often glass-plate negatives. I determined to rescue as many of the Churchill images as I could. The result was my book Churchill, A Photographic Portrait, published in 1974.

After completing six volumes of the full biography in 1988, and the document volumes spanning the years 1914 to 1939, I bought a new fountain pen and several bottles of ink and set about writing a single-volume biography, Churchill: A Life (1991). This was the culmination of my Churchill work, and enabled me to focus on both Churchill the social reformer and Churchill the war leader.

Many people had asked me to tell the story of writing the Churchill biography. It has been a fascinating thirty-year journey. The result of these requests, from friends and strangers, was In Search of Churchill (1994). My son David took the photographs for the final chapter, about Chartwell.

A year before his death, Randolph Churchill had asked me to draft for him, as part of a book which he and his son wrote on the Six Day War of 1967, a 5,000-word essay on “The Jews from Moses to Nasser.” To prepare this for him, and to widen my own understanding, I drew several dozen maps of aspects of Jewish history. This stimulated me to prepare more maps, for myself, and for a lecture I gave at Oxford, “The Jews versus Geography.” Only my brief speaker’s headings for the lecture have survived, but what did emerge from that lecture was my first book on a Jewish theme, The Atlas of Jewish History (1969).

I put my Churchill hat on again when asked to give the British Academy Thank Offering for Britain lectures. There were three of them, published together as a small volume, Churchill’s Political Philosophy (1981). That same year I completed a study of the most difficult decade in Churchill’s life, Winston Churchill: The Wilderness Years. It went in tandem with a television series of the same name, starring Robert Hardy as Churchill and Sîan Phillips as his wife Clementine.

One of Churchill’s friendships, with the literary agent Emery Reves, inspired me to edit the letters and messages they exchanged over a period of more than twenty years. The book, Winston Churchill and Emery Reves: Correspondence was published in 1997, sixty years after the two men had first met.

In my [recent] Churchill endeavours, three books have been published. The first is Churchill at War: His ‘Finest Hour’ in Photographs, 1940–1945 (2003). The second was Churchill’s War Leadership (2004). The third was Churchill and America (2005). This last is a study of Churchill’s sixty-year “love affair” with the United States, in all its moods, setbacks, and successes.

On the tomb of the nineteenth century Church historian Bishop Mandel Creighton are inscribed the words: “He tried to write true history.” Like the bishop—who was a member of my own college at Oxford—I believe that there is such a thing as “true history.”

In my Churchill researches between 1968 and 1988 I read every page of an estimated fifteen tons weight of documentation. The material available in archive is formidable and revealing—revealing of every facet of policymaking, of success and failure, of friendship and opposition, of cause and effect, of mood and motive.

In my own published work, I have avoided the word “perhaps.” It is for the historian either to say what happened, or to say that he cannot discover it. To say, “Perhaps it was like this” is to mask a failure to get to the bottom of a problem: and failure in historical research is no crime. It is one of the hazards of the profession.

Not only do I believe that it is possible to tell a true and straight and clear tale, I also welcome any corrections and amendments and additions to what I have published. My work has continually been enhanced by those who have written to me on matters of detail—to point out errors, or to correct lack of clarity, or to add new factual dimensions.

In my dictionary, the word “pedant” is a paean of praise, and “nit-picking” is a worthy art.

Altogether Sir Martin published fifteen books on Churchill-related themes as well as six volumes of the Official Biography and twelve of the accompanying volumes of documents that are available from Hillsdale College Press.

Text © Martin Gilbert and used with permission.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.